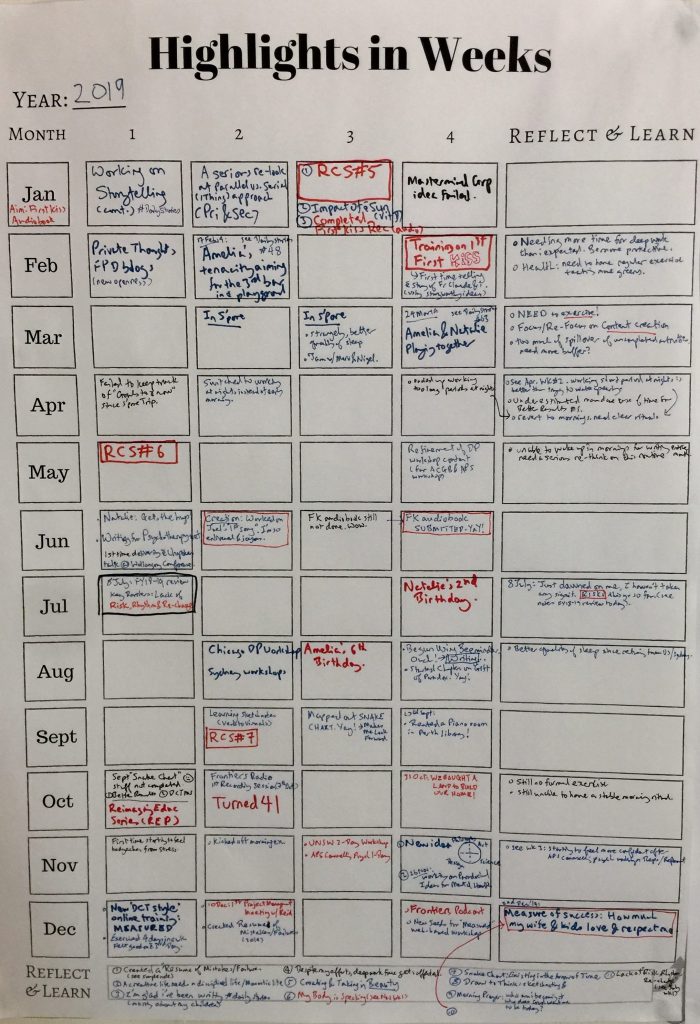

Two years ago, I started a project of capturing highlights on a weekly basis, previously called “A Year in Weeks”. I shared my private reflections and my personal learnings from looking back at 2018.

In today’s article, using the template I’ve come up with, now called “Highlights in Weeks.”

I’m gonna to share with you my reflections, learnings and blunders in 2019. I know, it’s nearly the end of the 1st quarter of the year. We’ve been focused on getting the Deep Learner workshop ready, launch a podcast, and preparing for the final touch ups to our book, Better Results.

Why Capture, Reflect and Consolidate The Year?

But first, I want to say why I’m doing this. To lead a memorable life, one has to re-member. And given that I’m 42 this year, I figured I might have at best, about 40 more of these Highlights in Weeks left in me. This heightens not just a visceral awareness of my mortality, but also, to live deeply in a way that I intend, and maybe less likely for me to end up saying, “Oh my goodness, where has the time gone? How did I waste it away?” which is a pretty common phrase.

As you might notice from the previous year, I also changed the title from “A Year in Weeks,” to “Highlights in Weeks.” I took inspiration from reading the book by Jake Knapp and John Zeratsky, Make Time. Since then, I’ve tried to start the day by thinking and noting in my calendar the one highlight event of the day. This could be a walk around my practice in Fremantle, writing music, taking my daughters for a bike ride, or even as mundane as getting a manuscript or research paper done, replying emails, etc.

Doing that “highlight” event gives me a sense of a day well spent.

For example, just this week, I spent the entire Monday devoted to writing and re-writing the outline the new course Deep Learner. It’s something I want to get done, but I’ve been held up for the last two months, as I keep excusing myself with “more readings, more researching.” At the end of last Monday, I was spent. But I was so glad that the bones and the heart of the course curriculum is crafted up to a point that I’m now proud of.

MY RESUME OF FAILURES AND MISTAKES (2019)

Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes.

~Oscar Wilde, Lady Windermere’s Fan

One of the ways I can learn from experience is to learn from mistakes. I created a tag in my simplenote app (this is where I do all my initial writing and note taking) labelled the tag “mistakes“. This consisted of general mistakes/blunders/errors in personal and work life, and clinical mistakes I’ve made in therapy.

By creating a resume of mistakes I hope that I can spot patterns.[1] By getting into the habit of updating this “inverted resume,” I hope to nudge my relationship with errors; one way to tell if someone if more in performance mode and less of a learning mode is to examine their reactions to mistakes (See this related post, Blackbox Thinking for Psychotherapists). Growing up in Singapore, where high performance is almost like a national sport, has perhaps contributed to my conflation that failings equals failure. Then again, as Nancy McWilliams pointed out, therapists in general are highly often self-critical. In order to grow, we need to slant towards a learning mode.

General Mistakes

A. Mastermind Group idea failed (wk 4 jan):

I intended to bring together a mastermind group for folks seeking a community to support and guide their deliberate practice efforts. However, it became near impossible to take flight. This was due to the lack of foresight that I’m dealing with people from all over the world. Many were interested, but I hadn’t planned it in my schedule to accommodate the different time zones.

B. Lack of Regular exercise (Feb to Nov):

I had planned to exercise more regularly, but for most of 2019, this didn’t came to be. I only managed to figure out a way to do so in mid-Nov, which was as soon as I got up (before my kids where away), I rushed to put on my “exercise” t-shirt. That’s all! Because as soon as I’m wearing it, I’m bound by the uniform to act accordingly and I proceed to my backyard to do back stretching, burpees and some weights. This hasn’t always been successful, but I’m interleaving morning exercises with bike rides, and once I find a basketball court nearby, I just might return to shooting hoops. Besides music and skateboarding, basketball has been integrate to my childhood play history.

C. Worked too long periods at night (wk 4 Apr).

One of the things I noted at the start of 2019 was to “Reduce/remove work time when it’s dark . I felt the detrimental efforts at the end of Apr’19.

But the reality was that I had to work at some nights, especially with the book writing project with Scott Miller and Mark Hubble, who were in the other end of the world in US.

I found a workaround:

– If I had to be at my home office in the evenings, work in short bursts. No more that 2hrs.

– If I worked in the evenings, I shouldn’t expect myself to be in my writing mode in the early mornings.

D. Unable to consistently wake up in the mornings to write.

See the previous mistake. Even though I had slept later, I somehow expected to wait up at 545am to write before the kids get going around 715am. In addition, maybe this is the Singaporean in me, I have a tendency to go to bed after midnight, even if I’m not working.

It is only since the start of 2020 that I’m beginning to appreciate that not only because of age (41), but also of the cognitive demands I put myself in the day, I need my sleep! My sweet spot seems to be around 7.5hrs. Much more than I previously had a year ago, which was about 6.5hrs. Reading Matt Walkers book Why We Sleep, and having a deeper appreciation of what the expertise and learning literature is saying about rest, made me more reverent to going to bed on time. I now aim to get to bed by 10-1030pm, do some reading and snooze away…

E. Underestimating the Effects of Planning Fallacy:

Even though I’m well aware of the cognitive bias of planning fallacy, which is that things take longer that you’ve planned, and even though this was noted in my 2019 post, I still fall trap to this! Daniel Kaheman is spot on about this. Even when you are aware of cognitive biases, it doesn’t necessarily inoculate you from it.

For example, I had planned an hour in my diary to read this blogpost. In reality, with the editing, inserting the hyperlinks and formatting, this took 3.5 hrs!

A slippy planning fallacy mistake I noted on 26th of Apr’19, Titled “Lost Time”

*”I spent too much time dealing with tech stuff. Meddling, organising, etc, and not on actual productive stuff. For example, I spent more than an hr this morning just trying to get iBooks synced from my phone to desktop. I could simply have lived without the sync, since i am going to export it to simplenote anyway. I need to limit/constrain this using the gestimer clock.”

To assist me in this, quite frankly, agonising mistake, I’m returning to the principle of aiming to do less in a day, and focus on 1 to 2 keys things per day. And if I need to get sidetracked of figuring out stuff, I need to write a note to deal with it later, not in that moment of deep work.

For my clinical practice I now make it a rule in my schedules that I get a 15min buffer between sessions. This gives me either a breather or wiggle room when a client needs bit more time.

Lack of Risk, Rhythm, and Recharge

Spotting local mistakes is the first step. The second step requires you to categorise and observe for any emergent patterns.

Around the first week of July 2019, it began to dawn on me that essentially, what I was learning from my “highlights in weeks” 2019 chart is that I lacked, “Risk, Rhythm, and Recharge.”

Let me explain.

Risk: I had been rather gun-shy about taking certain calculated risks, liking releasing new training ideas, new mini-books that I’ve been working on. Given that I had been busying myself with other projects and clinical practice, I wasn’t exactly stretching out of my comfort zone in this aspect.

Rhythm: I also noticed midway in 2019 that I was really lacking a sense of rhythm in my daily living. If I was a drummer, I was beating out of sync.

Recharge: I knew getting involved in music writing and playing has a profound impact on my wellbeing. In terms of charging my batteries, I had let this slip.

And her’s what happens when I haven’t recharged. I become a grouchy Monster towards my kids. Here is where it hurts the most. Because of the lack of “risk, rhythm, and recharge”, one of the painful consequence is that I get short tempered with my kids. In 2019, I had raised my voice more than I would like to admit. This is the reason, as you will see in the final point in the upcoming Part II of this post, I state that my main learning about “the measure of success” is related to my relationship with my wife and kids. More on this later.

Clinical Mistakes

Whenever I ask therapists to thing of their mistakes, often I get the look that says, “where do I even begin?!”

Again, like the General Mistakes above, what’s critical is not just to spot individual blunders in therapy, but to take one step up the ladder of abstraction and look for the underlying patterns.

Looking back at my notes in 2019, I see that there are 2 patterns of mistakes that I’ve made in my clinical practice:

A. Patterns in Unplanned Termination:

When there were unplanned terminations of therapy, there were a handful of cases that the Session Rating Scale (SRS, an ultra-brief measure of work alliance that I use at the end of every visit) had slightly declined in the last 2-3 sessions. Had I been keeping a closer eye on this, I could have an important conversation with my clients about this. Since realising this, I now have my rabbit’s ears and **look for contrasts”, either good or bad, and then inquire about the differences, so that I can adapt and feed-forward the feedback.

Case in point: I had a client like who dropped-out of treatment at the 9th session. I reviewed the graph and sure enough, the SRS had sliced downwards, just a little bit, for the last 2 sessions. I had learned from the client that I was getting too abstract for him, and did not point in more concrete psychological terms what he could do. I reviewed the last 2 sessions. He was right. I was too in love with my ideas, even though it wasn’t making sense to him.

B. Move it!

Another pattern I spotted was strangely effort, about my willingness to move when needed! My office is situated at the heart of Fremantle, and sometimes there might be town events going on (or just noisy patrons of a nearby bar). I had contemplated moving to my colleagues office which was tucked in another corner of our centre and less noisy. I asked my clients if the noise on the street affected them. They all said, “it’s fine. No worries.” But when I looked at the level of engagement via the SRS, they almost consistently experienced lower engagement then their previous session!

My hunch is that though clients wouldn’t explain it this way, but I suspect the noised had significantly affected the emotional climate of the session. From a more neurological perspective, our auditory processing is closely linked to our emotional states, which is why music can move people in all sorts of ways. So if the environment was too noisy, the signal to noise ratio might have affected their ability to process in-session.

More critically, there is a larger pattern I can extract, which is being willing to physically move a little more in my seat. It’s so easy to sink in comfortably into my chair. But one of the reasons I use chairs with wheels is so that I can use this to move within the physical space, depending on the context and when different levels of emotional content comes to bare in therapy. When I do move, it seems to prime a mental shift in my mind.

Nonetheless, Note to self: When it gets too noisy, get off your butt and be willing to move!

Now, to be sure, these were not the only mistakes I’ve made in my clinical practice. They were other blunders like getting lost in the details, not engaging everyone in the family during a conjoint session, overwhelming a client with questions in a first session (the irony is not lost on me that I wrote a book on this very topic). These were what I call random-errors. They were specific to the case, and were not generalisable to a pattern that I can address in my development. These were stuff I had to learn to adapt specifically for that session or client(s).

Making a distinction between random and non-random errors is crucial in your deliberate practice efforts. For more on this, Scott Miller and Mark Hubble and I addressed this in our book, Better Results.

Only a fool learns from his own mistakes. The wise man learns for the mistakes of others.– Attributed to Otto von Bismarck.

~ as cited in Gerd Gigerenzer’s book, risk savvy, p. 67

Oh, on a related note about mistakes, I highly recommend that you listen to the podcast by Ben Fineman and Carrie Wiita, The Very Bad Therapy Podcast. (They were also featured as Ben and Carrie reflected on their learning experience on the Frontiers blog, 4 Lessons from 20 Weeks of Very Bad Therapy) On the podcast, you get to hear the inside scoop from client’s perspectives of negative experiences in treatment, as well as reflections from professionals about those cases.

In the upcoming second part of my reflections on 2019, I take one step further and extract primary personal learnings based on the ins and outs of what transpired in the year.

If you interested to become optimizing your mistakes and successes and become a deep learner, join us for a newly minted web-based workshop (not just a stream of information, but content, community, and practical applicable ideas) called Deep Learner: A Psychotherapist’s Field Guide to Extend Your Mind and Harness Wisdom into Clinical Practice. I believe that becoming a deep learner is the prerequisite of living a deep life.

1. The kick-off date is 30th Mar 2020, Monday, and

2. Registration closes on 27th of Mar, 2020, Friday.

For more information, click here. If you want to be the founding batch of this course and enjoy a SIGNIFICANT 29% discount (about $140 in savings. Only application for founding members), make sure to subscribe to the Frontiers, and watch of for the promo code in the March 2020 Frontiers Newsletter.

A man who has committed a mistake and doesn’t correct it, is committing another mistake.

~ Confucius (Chinese thinker, 6th to 5th Century BC)

Footnotes:

[1] The idea of a “resume” of mistakes takes inspiration from Ray Dalio’s Principles, and organisational psychologist, Adam Grant.

Thanks Daryl – how refreshing to hear someone not just owning their mistakes but actively looking for them! A fine example we can all follow.

Take care

Barry