Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 07 June 2024

Today, I want to share with you how one clinician used the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA) to guide her professional development efforts, so as to leverage her outcomes.

Feel free to jump straight into the clinical example if you wish.

The Paradox of Focusing on the Outcomes

But first, I would like to address a concern that I get from clinicians who have been measuring their clients.

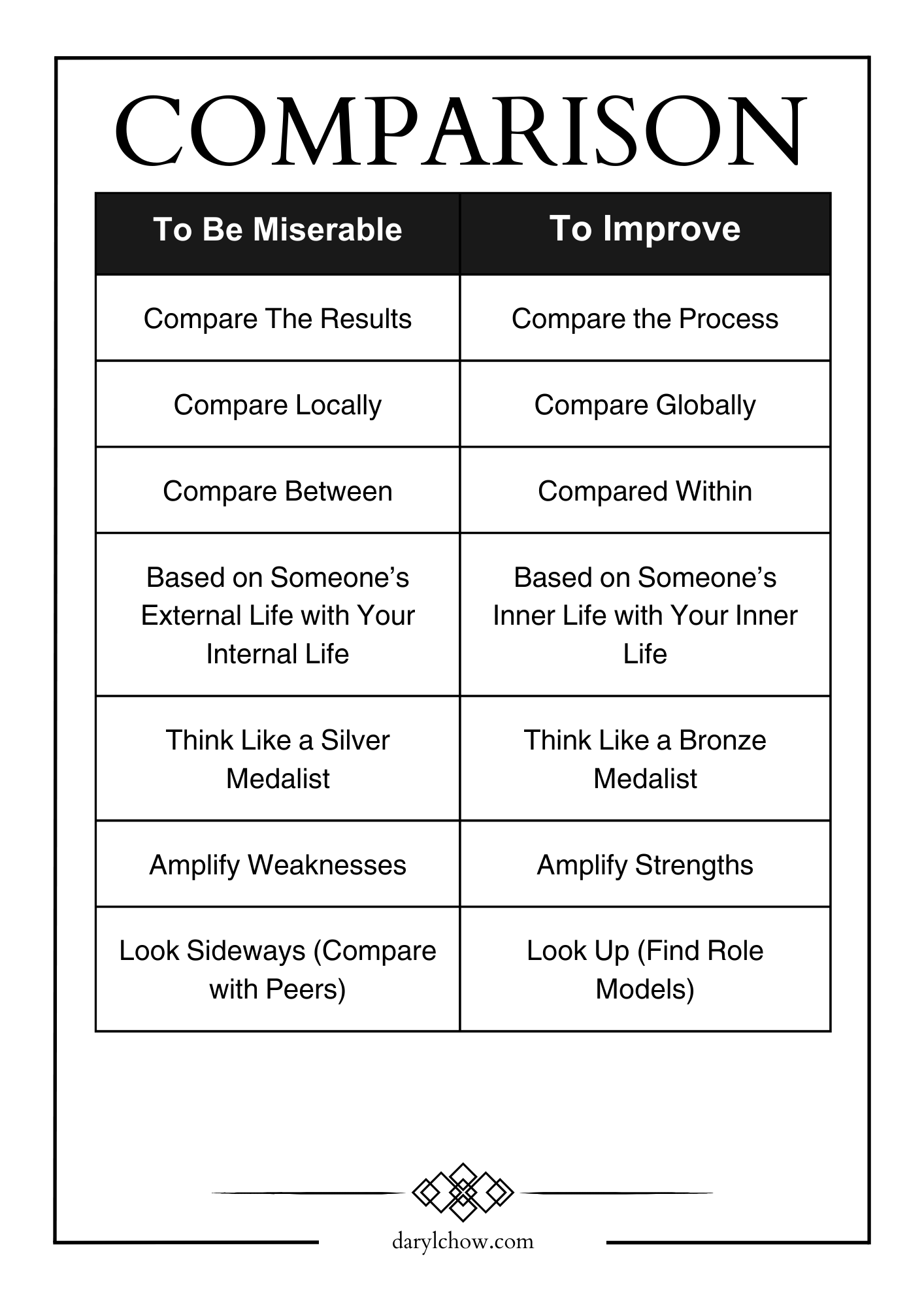

I sometimes worry that all this emphasis on measuring outcomes leads you to become overly concern about where you are compared to others.

When starting out, it’s useful to have a sense of “where you are at,” relative to others. This gives you a sense of your ability, some sanity, and maybe even help with lowering impostor syndrome.

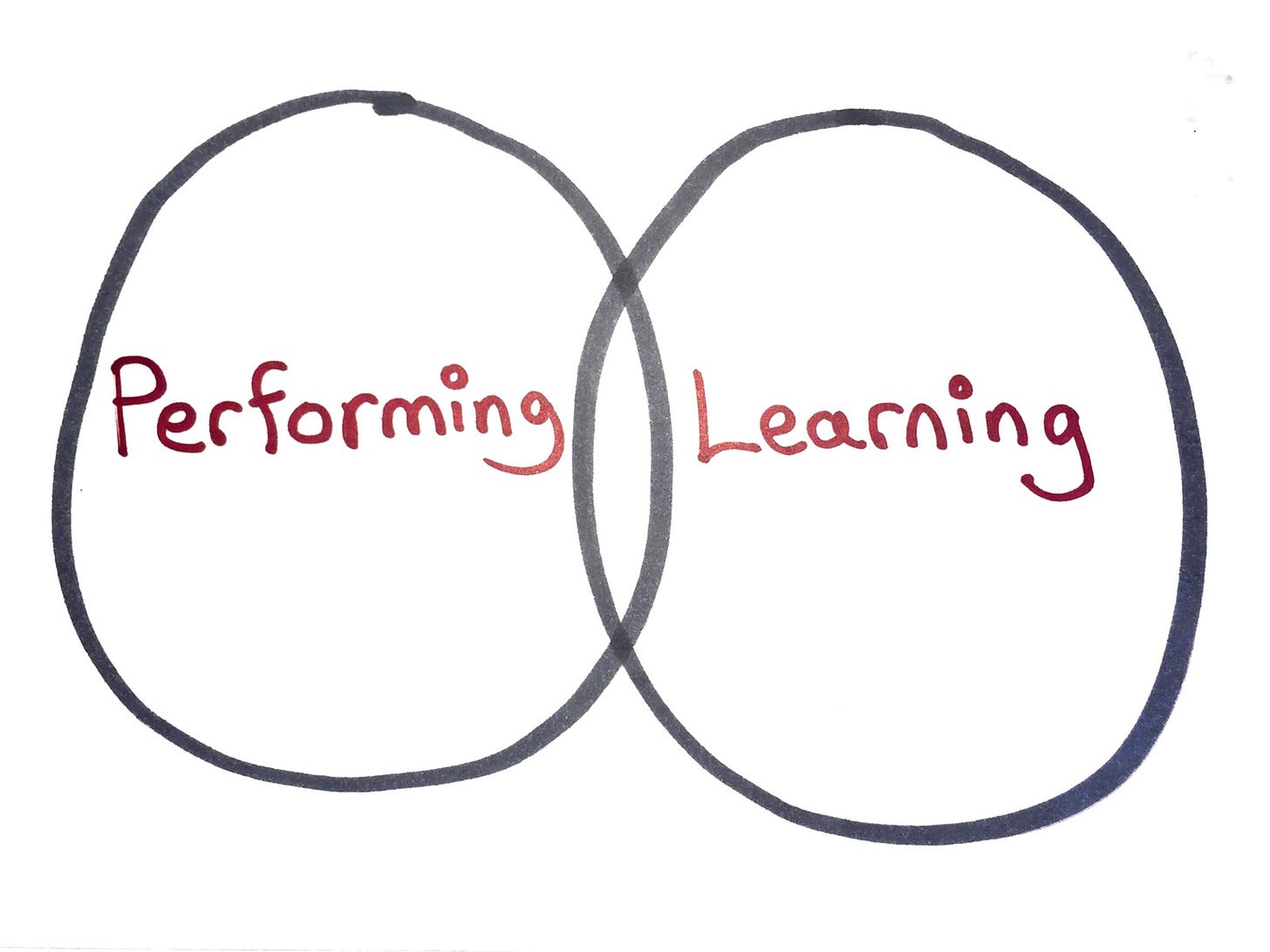

However, as I’ve been monitoring my outcomes as a therapist since 2004-05, once you’ve established that you are are doing fine and need not quit your job (i.e., that you are average), I’ve not found it useful to compare with others, simply because it puts me in a disquieting, anxiety-provoking “performing” mindset.

Focusing solely on the outcome is not going to get me the outcome.

Rather, I want to develop a deep learning mindset, and compare within my past (i.e., compare with my baseline), and not compare with others.

RELATED ARTICLE:

This sounds trivial, but it’s not. I found that if I overemphasise on “performing”, it impedes my openness to really learning, and ultimately, improving.

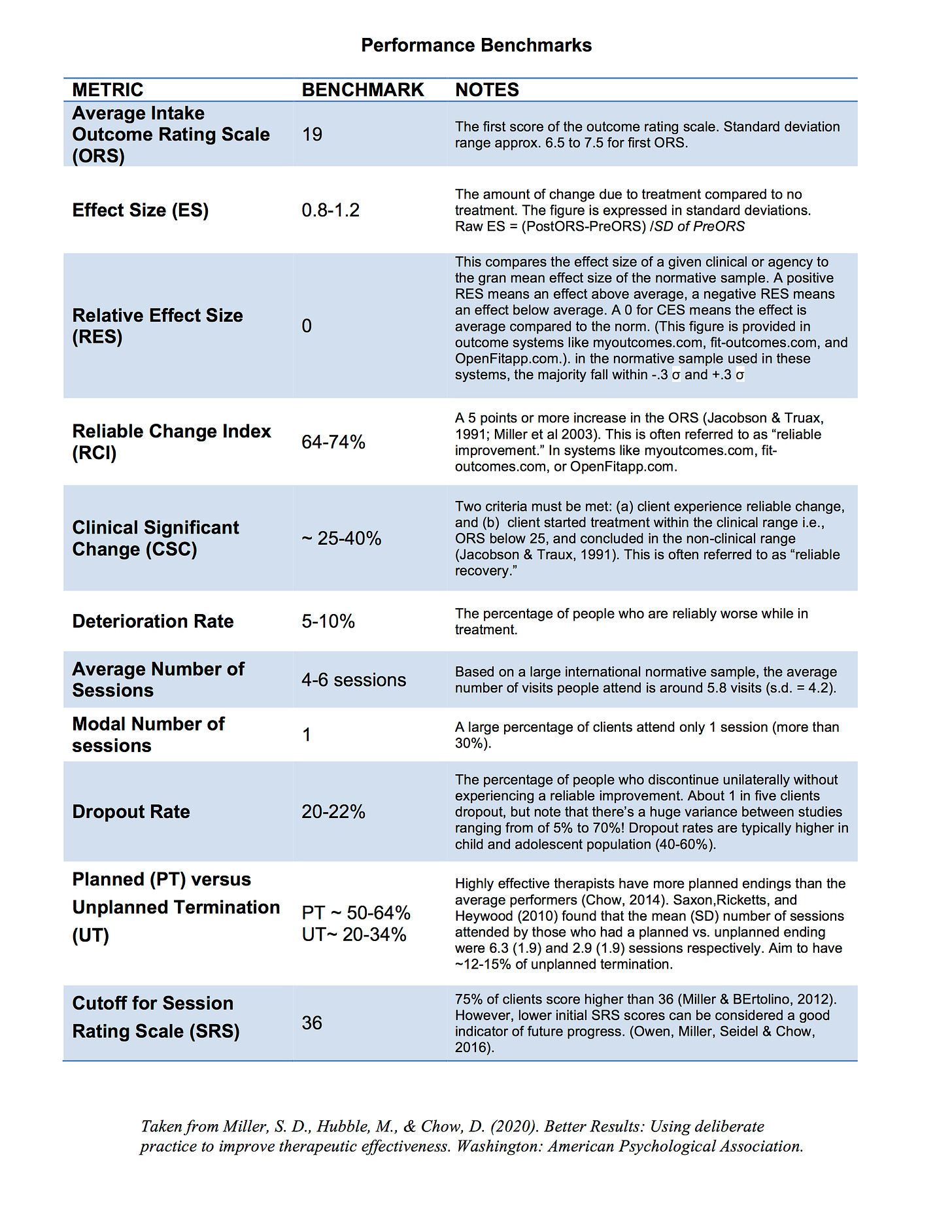

In gist, it would be useful for a clinician to first establish your baseline, and initially get some reference to normative benchmarks (see table below), and then continue to monitor your outcomes down the road (outcomes goals), as well as your efforts (process goals) to achieve that.

As you evolve, the aim overtime would be to “reduce negative variance” (i.e., reduce dropouts and deterioration rates), and “increase positive variance” (i.e., not sticking to a formula, and increasing the various possibilities of how one can co-construct a good outcome for a given client. )

Okay. Now that I’ve gotten that out of the way, let’s take the next step to lay the conceptual grounds.

For the purpose of illustrating the case, let’s zoom out—like in a Google Map— before we zoom in to the weeds. 1

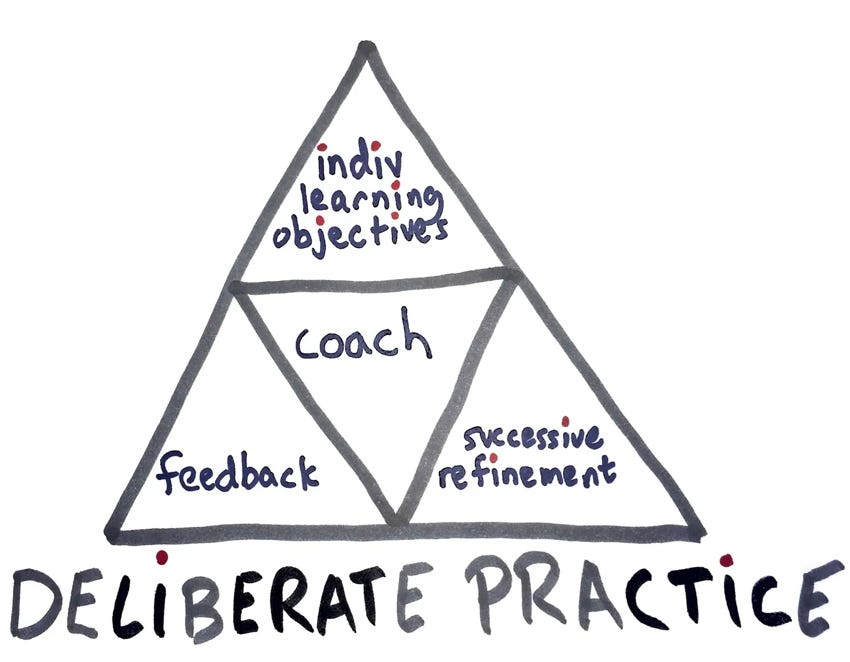

Based on the deliberate practice (DP) four pillars, the TDPA is targeted at helping clinicians at the top of the pyramid, Individualised Learning Objectives:

For more about deliberate practice, see this article:

What Does Deliberate Practice Look Like? Look at What’s Onstage, Backstage, and Offstage.

Now that you see where the TDPA fits into the deliberate practice framework, in order to see how each step of your professional development builds upon each other, let’s zoom-out to see the macro picture of what the journey of individualised professional development entails.

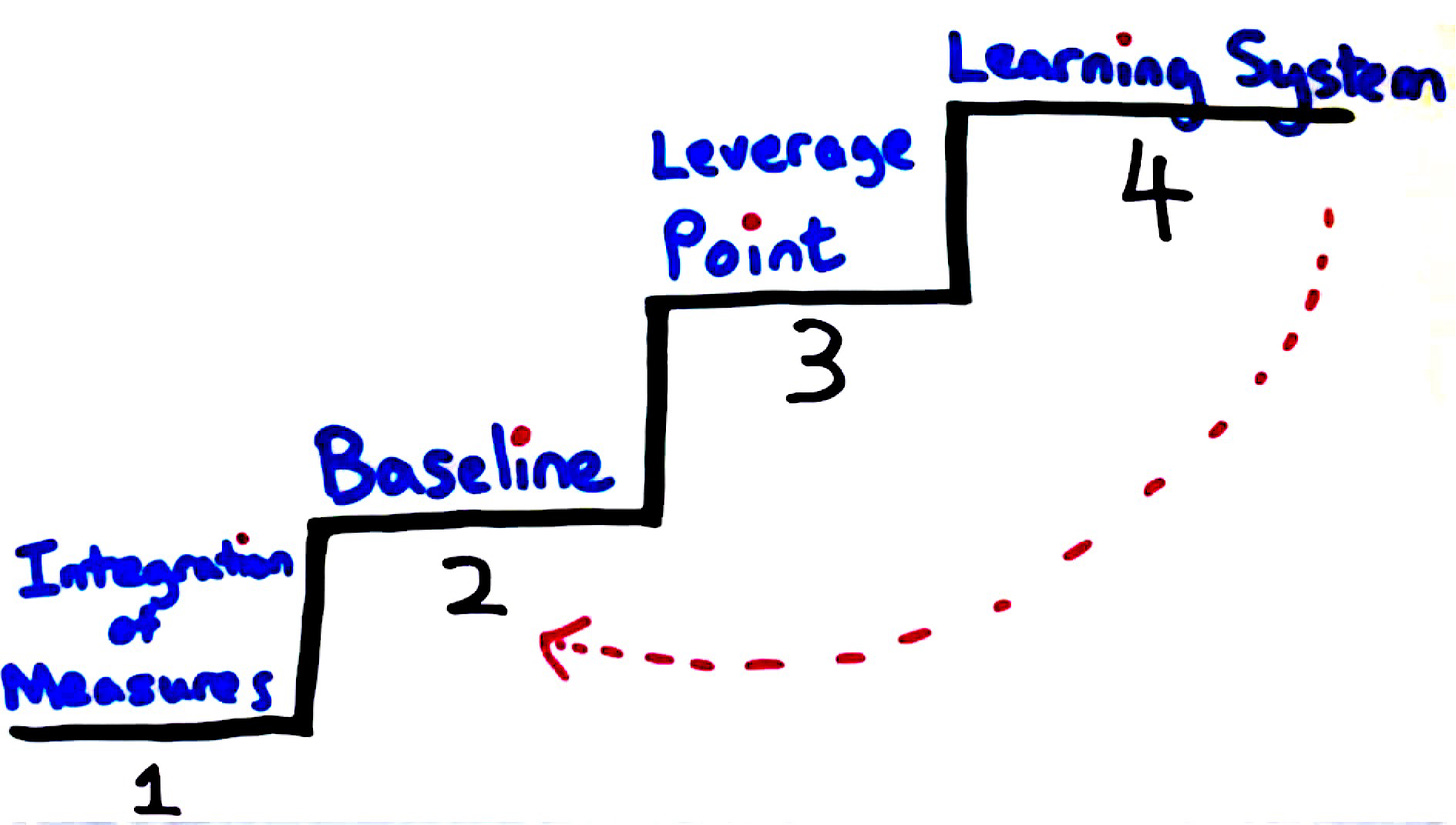

There are four key levels to note:

Level 1: Integrate the use of feedback measures in clinical practice

Level 2: Develop Your baseline

Level 3: Identify Your Leverage point, and

Level 4: Develop a learning system

There are two foundational steps (i.e., Levels 1 and 2) that need to be established before going into the TDPA, and one more step (i.e., Level 4) once you’ve figured out where to invest your DP efforts.

When you’ve moved beyond your current growth edge at Level 4, a new baseline is established (i.e., Level 2), and the cycle continues with a new personal learning edge to pursue.

How to Identify Your Leverage Point

Now that you have the big picture about DP, and where the TDPA sits in the sequence of things, let’s now dive to the next level.

As you set out to systematically employ the TDPA, there is a three-step sequence to help you in the process—and you’d see later on how a clinician does so.

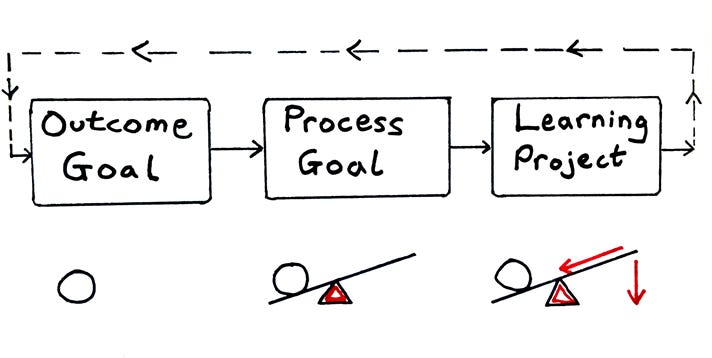

The Outcome Goal, Process Goal, and Learning Projects (OPL) framework is designed to help you gain clarity and specificity in order to ensure that your efforts in deliberate practice translate to better client outcomes

Outcome Goal (OG)

First, the Outcome Goal is the “What” you are trying to achieve. The OG is crafted from your baseline data achieved at Level 2.

The OG is the one that we are most intuitively familiar with. What is the end goal that we want to achieve? Saying that we want to improve our effectiveness isn’t enough.

Process Goal (PG)

Second, the process goal is the “How to” that leads to impacting the stated outcome goal. Specifically, the list of items in the TDPA are a smorgasbord to get you thinking about what process goals to aim for that are linked to the outcome goal.

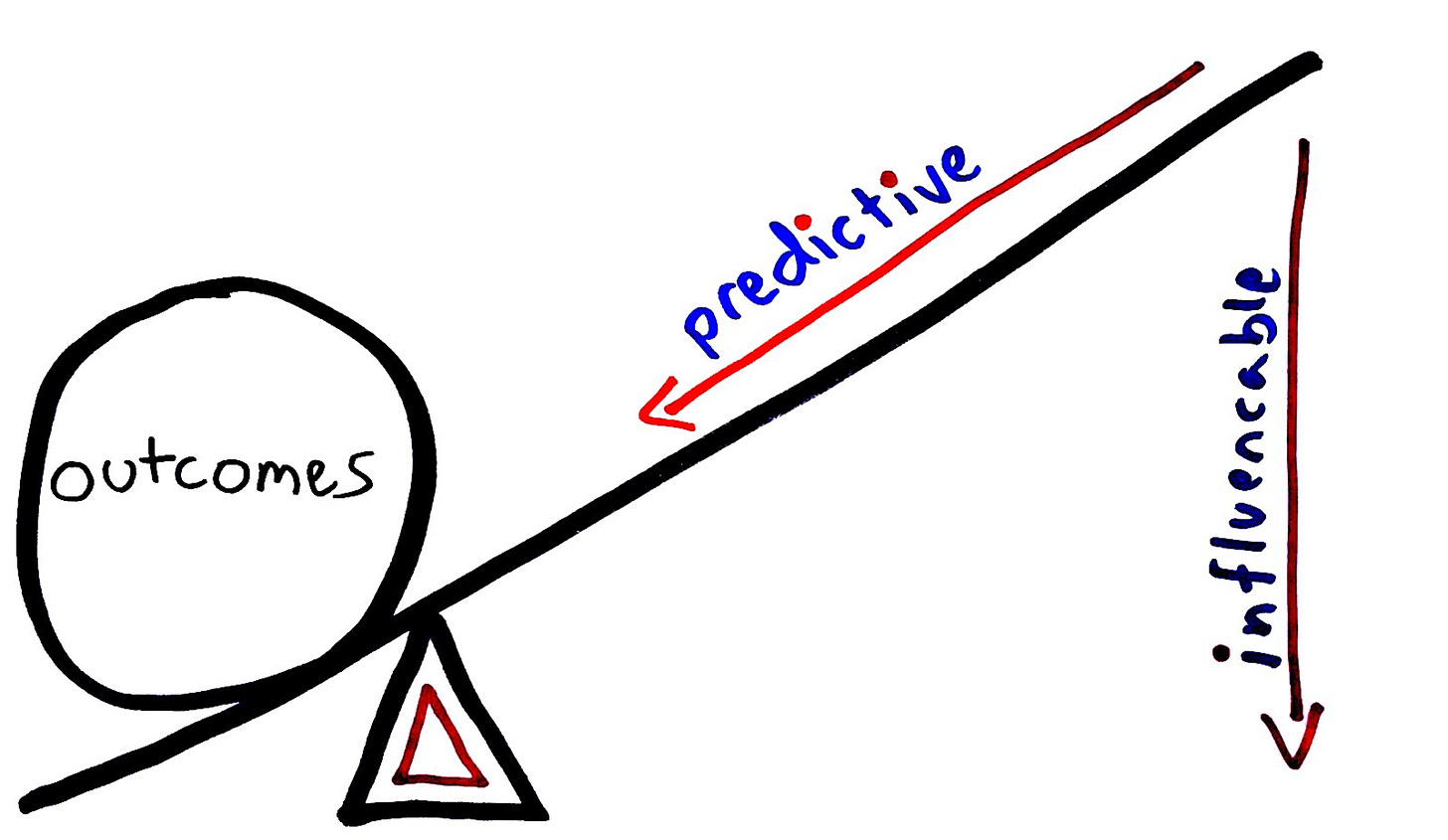

Once your outcome goal is defined, we need to figure out the process goal. The PG is about creating an ongoing system that leads to the outcome goals. As mentioned in a previous article (see FF186), a guiding principle of a good PG is that it must be predictive of influencing the outcome goal, and it must be influenceable i.e., something that you can work on.

Learning Goal (LG)

Finally, your learning project is the nuts and bolts of what you need to do to influence your process goal, that is tied to the outcome goal. A LG (not the TV) consists both of inputs and outputs, and it is constantly held at the back of the practitioner’s mind during a time bound period of cascading the impact from the process goal to the outcome goal.

The question you’d be thinking about is this:

What do I need to learn at this stage of my development, so that I can influence my process goal, and in turn, impact the outcome goal?

It is worth emphasizing that the learning project and the process goal must link to the outcome goal. This is why, at first blush, the OPL sounds relatively easy. However, when you begin taking the three primary steps in the OPL framework, you will find that the effort involved to clarify, specify and quantify the elements is challenging.

Now, armed with the OPL framework in mind let’s turn to psychologist, Janice.

A Clinical Example of Moving the Giant Outcome Goal

Janice is a therapist with about 7 years of clinical experience. She worked in both inpatient and outpatient mental health clinics. 2

Once she had enough cases for a reliable, evidence-based analysis of her clinical performance, she began the process of identifying the outcome goal. In an effort to identify the area with the most leverage on improving her results, she created a spreadsheet listing each client’s data (i.e., outcome and relationship scores) and other details. In a separate column, a distinction was drawn between those she treated successfully (reliable improvement) an unsuccessfully (lack of reliable change, deteriorated, or dropped out after the first session). Next, with the spreadsheet open on her computer, she starting reviewing the progrsss notes of her closed cases, sorting and “solving for patterns.”

RELATED ARTICLE:

Four were immediately apparent. First, many of the clients Janice treated unsuccessfully were originally seen in an inpatient context. Second, client progress and the quality of the relationship as measured by the Session Rating Scale (SRS) covaried. Specifically, SRS scores generally improved over time for those in the successful group while remaining stable (whether beginning high or low) among the unsuccessful.

Third, no difference in initial SRS scores was found between clients who made progress over the course of care and dropped out, deteriorated, or did not improve. Janice knew this was a potential target for DP, given evidence showing lower initial relationship ratings are associated with better results at the end of treatment.

Fourth and finally, the modal number of sessions Janice had with clients was 1,

with 32% attending only a single visit.

As a professional whose identity was closely tied to her commitment to excellence, Janice’s performance data evoked both anxiety and a strong sense of inadequacy. On the recommendation of her supervisor/coach, she chose to spend the next month engaging in revitalising her desire for learning, getting some good quality inputs, and engaging in reflection). While she was typically focused on achievement and performance, she worked at being open to growth instead of just competence. Although the change in mindset did not come easily, spending time with her data was what did the trick. She marvelled at how the routine administration of simple measures could reveal patterns that had, despite her best intentions, eluded detection.

Specifying the Outcome Goal

Eager to begin actively taking steps to address the problems identified, she returned to the exercise of choosing to choose a single, committed outcome goal on which to work.

Once again, she found herself struggling.

Consultation with her supervisor/coach revealed the issue. It is a common one; that is, focusing on the “how” before being clear about and committed to the “what.” For example, given the various patterns of her SRS data revealed, she decided to work at developing skills related to eliciting more detailed, critical feedback3 She further concluded adding more organisation and focus to her sessions4 would improve results with clients she initially met in an inpatient setting and treated for longer periods.

Returning to her spreadsheet to revisit the patterns and choose a single, committed outcome proved to be the solution. After recording the four patterns in her journal, she spent a week thinking about the clients with whom she had been unsuccessful, reviewing the case notes for each:

- Clients starting off in an inpatient context (~65%) routinely failed to follow through with scheduled outpatient appointments.

- Clients whose SRS scores did not improve over the course of care were significantly more likely to end treatment with little or no improvement in ORS scores.

- Clients with high initial SRS scores was equally likely to end treatment unsuccessfully as successfully.

- Nearly a third of Janice’s clients did not return following their first session.

With help from her supervisor/coach, Janice chose what she believed would be the easiest to address. In this instance, that “low hanging fruit” was the high number of unplanned terminations by clients first seen in an inpatient setting.

Stated specifically, her outcome goal was reducing dropouts for clients transitioning from inpatient to outpatient from 65% to 40%. The remaining three performance concerns were labeled, “aspirational” and set aside for possible DP in the future.

Specifying the Process Goal

Next, Janice had to figure out the process goal that would decrease the dropout rate of inpatient clients.

After watching video recordings of several representative sessions together with her supervisor/coach, both agreed the conversations conducted with hospitalised clients were more unfocused in nature than typical outpatient visits. Consistent with Janice’s lower rating on TDPA 3. Relationship: Effective Focus. “How do you establish goal consensus in the first and subsequent sessions?” (scored 3/10), this led to the formulation of a process goal and learning project organised around establishing and checking goal consensus in first and later sessions. However, when Janet subsequently interviewed several former clients, a different angle emerged. A number mentioned being surprised by her questions about, and characterisation of not continuing with sessions on an outpatient basis as, “dropping out.”

Discussing her findings with her supervisor/coach, the two agreed hope and expectancy factors were implicated, one element of which Janice had also rated low (TDPA 2. Hope and Expectancy, regarding role induction, setting and monitoring client expectations, and adapting the treatment rationale to foster engagement and hope; scored 3/10) on her initial completion of the tool.

Janice immediately went to work creating a learning project, taking time to brainstorm, talk with colleagues, and research ideas related to operationalising her process goal.

Based on finding clients frequently struggled to parlay improvements made while in the hospital to their lives following discharge, she created what she later termed, her “safety-net” system. Introduced early in care, it emphasised the critical role she would play, and resources she could bring to bear, in supporting lasting change for the client. Appointment reminders and help with arranging transportation to and from sessions were two among the many aspects of the system specifically designed to reduce dropouts.

Together with her supervisor/coach, Janice continued to monitor her performance data as she put her plans into action. Six months later, she was disappointed when improvement in the percentage of clients failing to follow through with post-hospitalisation, outpatient sessions stalled at 50%.

At one point, she began actively considering replacing her committed outcome goals with one of her remaining aspirational goals. “Actually,” she said, “Nearly all of the items on the TDPA are things I could work on and do better at. How can I not try to improve on more of these?”

Completing the “anti-goal” exercise5 served to persuade Janice to maintain her current objective but reconsider her process goal. Addressing TDPA Factor 2 (Hopes, expectations, and role) had resulted in a decline in dropouts but she was looking for more. Returning to recordings of her sessions, and consulting the therapy blueprint she had created at the outset of her foray into deliberate practice, she noted the significant amount of time spent in initial visits conducting a thorough psychosocial history. It was an activity that had been ingrained in her clinical routine from her university days – and yet, she realised, the information gathered only rarely informed her work, delayed actively intervening to help clients, and often resulted in lower levels of engagement.

It was at this time, she read The First Kiss: Undoing the Intake Model…, which focused on the importance of the initial therapeutic encounters. In place of “taking” (paperwork, information gathering, long diagnostic workups), it encouraged therapists “giving” to clients, taking full advantage of the potential for change research documents occurs early in treatment of most. The same body of evidence reviewed in the book showed traditional “intake” practices resulted in higher drop out rates, slower progress, and more expensive care. It also identified an alternative, what is termed by Gassman and Grawe as resource activation. Instead of asking about the presenting problem, symptoms, and struggles, it involves actively soliciting information about client capabilities, motivations, and existing social support network.

At this point, Janice made a conscious choice to change her process goal from items in Relationship factors of the TDPA to Client Factors—specifically the item “incorporating your client’s strengths, abilities, and resources into care.”

In support of this new objective, she sought out research, training materials, and consultation. After several months, Janice’s hard work began to pay off. Interestingly, her discontinuation rates among those clients beginning care in an inpatient setting declined (from 50% to 18%) and the modal number of sessions she met with clients tripled (1 to 3). As often happens, such improvements influenced other performance metrics, including a rise in Janice’s overall effectiveness.

This “spill-over” effect was welcomed and rewarding. Even as Janice continued to struggle with working within a bureaucratic system, Janice described this process as a morale boost.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments