Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 29 Mar. 2024

Let the Data Speak

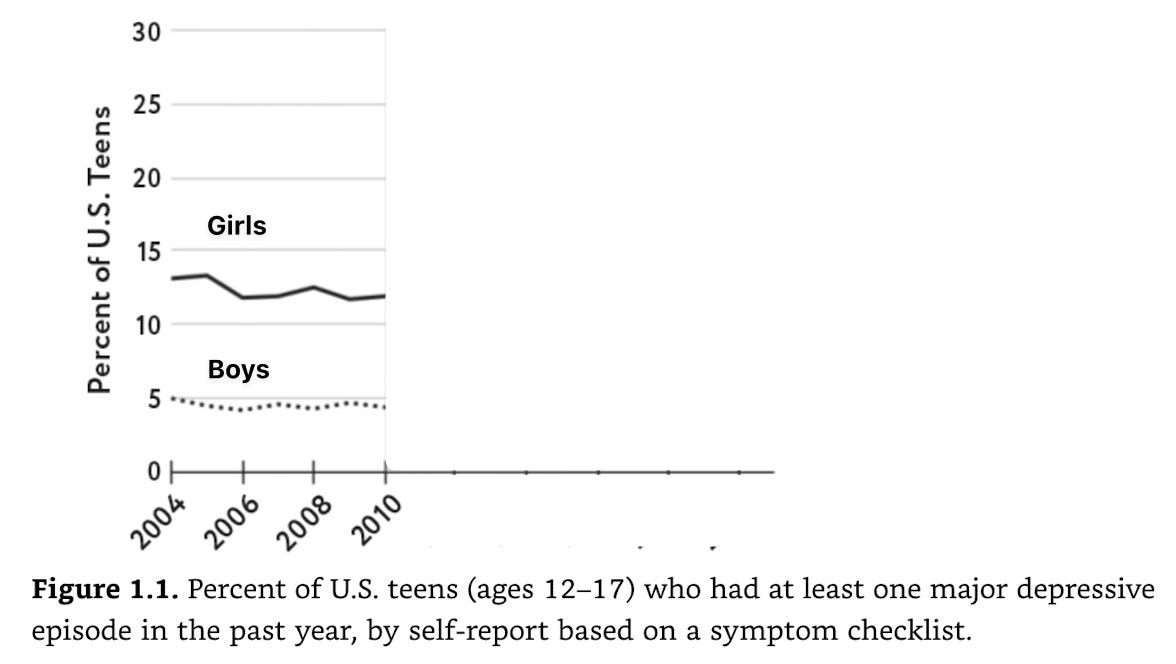

Take a look at the graph below. If we were to follow the lines up until 2010, besides the gender difference among teens (which we will get to later), you can’t say much about how things are changing over time.

Major Depression Among Teens

Now look at the same graph, this time stretching beyond 2010.

What has caused this rise of depression among teens around the period of 2010-2015?

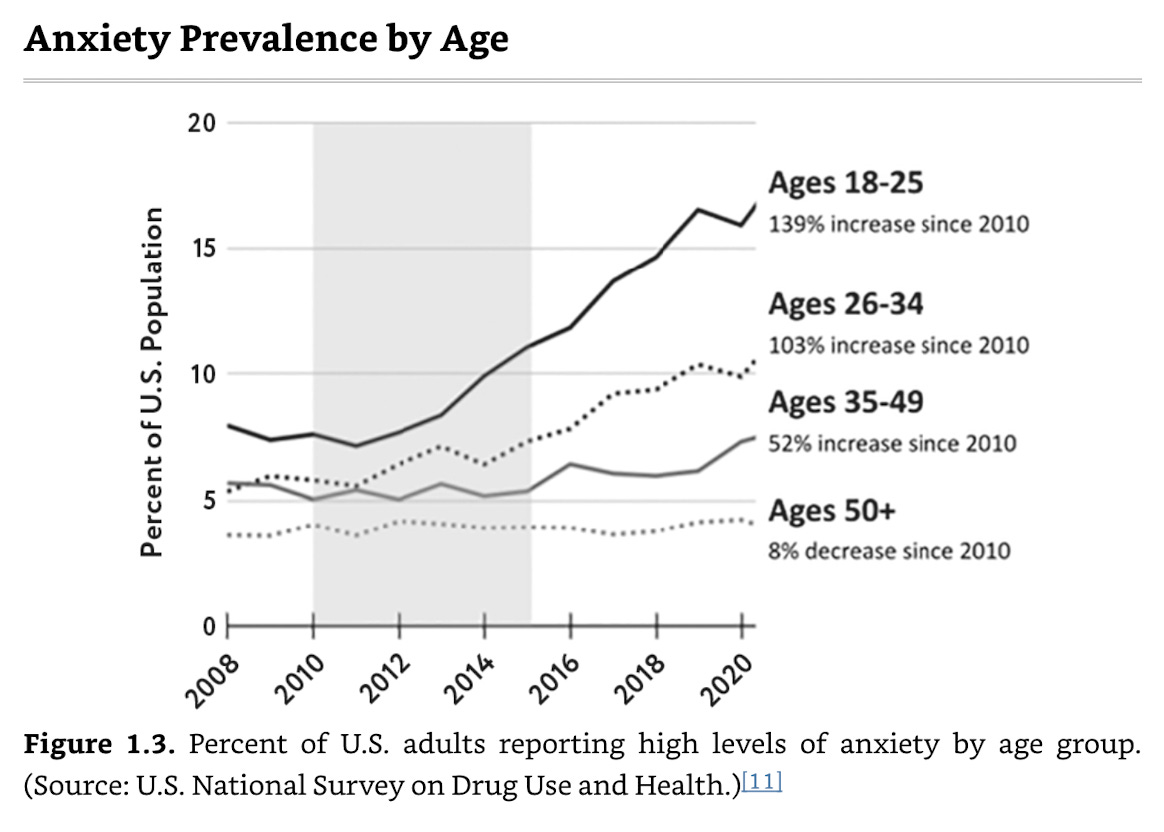

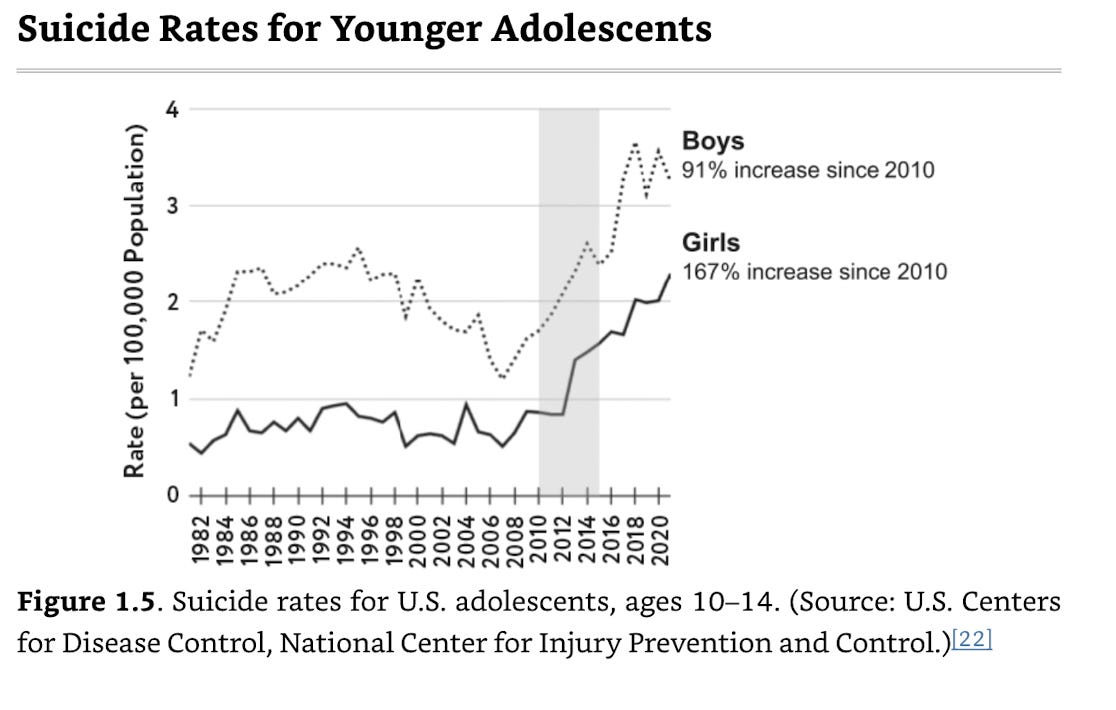

Before we answer that question, there’s more. This time, let’s look at the prevalence of anxiety, emergency room visits due to self-harm, and suicide rates for teens.

These graphs, taken from the latest book by one of my favourite social psychologist,

Jonathan Haidt, called The Anxious Generation, point towards an alarming evidence that many parents, teachers and mental health professionals have noticed in recent years.

There Must Be Other Explanations?

No other theory can explain this decline in mental health among the young, including economic crises, climate change, academic pressure, increase in self-report, and the age-old admonition from the stats professor that “correlation is not causation.”1

For more on why other competing explanations fall short, read

Jean M. Twenge post:

And why this specific impact on teen girls?

Haidt noted,

The rate of self-harm for these young adolescent girls nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020. The rate for older girls (ages 15–19) doubled (emphasis mine), while the rate for women over 24 actually went down during that time.

Haidt argues that a play-based childhood is now replaced by a phone-based childhood.

Specifically—you guessed it—by the use social media.

Which begs the question: What makes the period of 2010-2015 so unique?

The Ascent of Technology and the Descent of Our Kids

In 2010, the first iPhone with a front-facing camera was introduced to the world. Promptly, Samsung followed suit.

Haidt called the period of 2010-2015 “The Great Rewiring of Childhood.”

That same year, Instagram was created as an app that could be used only on smartphones. For the first few years, there was no way to use it on a desktop or laptop. Instagram had a small user base until 2012, when it was purchased by Facebook. Its user base then grew rapidly (from 10 million near the end of 2011 to 90 million by early 2013). We might therefore say that the smartphone and selfie-based social media ecosystem that we know today emerged in 2012, with Facebook’s purchase of Instagram following the introduction of the front-facing camera.

By 2012, many teen girls would have felt that “everyone” was getting a smartphone and an Instagram account, and everyone was comparing themselves with everyone else.

Over the next few years the social media ecosystem became even more enticing with the introduction of ever more powerful “filters” and editing software within Instagram and via external apps such as Facetune. Whether she used filters or not, the reflection each girl saw in the mirror got less and less attractive relative to the girls she saw on her phone.

While girls’ social lives moved onto social media platforms, boys burrowed deeper into the virtual world as they engaged in a variety of digital activities, particularly immersive online multiplayer video games, YouTube, Reddit, and hardcore pornography—all of which became available anytime, anywhere, for free, right on their smartphones.

Related Posts:

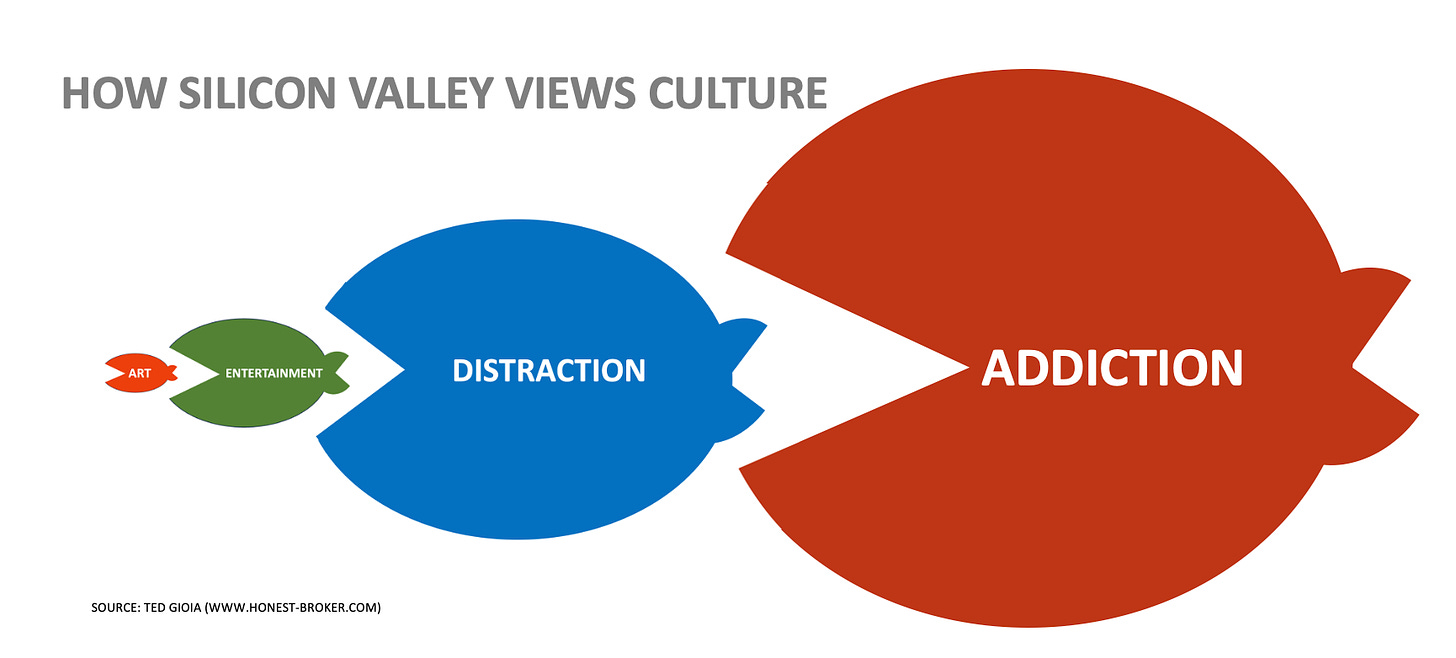

It’s Not About Distraction. It’s About Addiction.

Ted Gioia , another one of my favourite writers on Substack, recently illustrated in his excellent post, The State of Culture in 2024 that it’s not just about entertainment or distraction. It’s about addiction. The new dopamine cartel of the tech companies are trying to make you become “users.”

A Dearth of Unmediated Experiences

One of my concerns is how disembodied our experiences are becoming. I feel this when I’m teaching to large groups online. Yes, people are present, but I don’t feel them as I would being in the same room. I don’t get the immediacy of a tight feedback loop if I’m blabbering or landing on a point. I get more easily exhausted than an in-person context, which is often more energising. I still appreciate the opportunity to connect, albeit virtually. If you think about it, it’s quite a trip to be able to connect with people from all over the world.

But think about the Gen Zs whose primary connection are mediated primarily by their devices—and their mates are probably just 3 km away, not 30,000 km away from their homes.

When youths share with me about their social woes in sessions, I listen carefully to the nuance of the exchange, or at least their report of it, as I try to figure out who said what and why, and the intra-psychic conflict their are facing. They tell me about what they talked about, the stuck points, the hurts, the ghostings… And then I say something stupid like, “So you spoke to her on the phone or face-to face?”

“Oh no. It was via snapchat/instagram/whatsapp.”

“I see, video call?”

“Nooo… Text…”

Even though we are all carrying a phone all the time, from the bedroom to bathroom, who calls each other these days on the phone? A few weeks ago, a friend called me on the phone. I immediately went, “Is everything ok?” He said, “Er, yeah. Just thought I ring you.”

I suspect that, on a deep level, we need more unmediated experiences. Not just a fully immersive online game with your friends, but a fully bodied engagement of kicking that ball into the goalpost—and missing most of the time. Not just an exchange of information, but to connect in real-time, in the flesh. If not in-person, at least to hear each other’s voice; to hear our acoustic signature that is highly expressive of the hidden world of our emotions. An unintended consequence of the ascent of mediated experience might lead us to an increasing lack of social skills.

…To touch, to move, and to be moved. To be taken by things that travel at the speed of life, not at the speed of light. An antidote to anxiety is to reduce velocity.

I’m no Luddite, but we need to touch more of the people we are trying to relate to than touch our phones.

Read The Anxious Generation

I’ve been following

Jonathan Haidt work for awhile, and more recently reading his brilliant Substack

I’ve only just begun delving into Haidt’s book, but I had to pause as the hour grows late. If I continue, I might get grumpy on a Good Friday morning. So far, the book is sobering. I hope that readers of

Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development will join me in reading The Anxious Generation.

In addition, you can watch Haidt’s talk at the ARC forum:

Haidt’s central claim is this:

“Overprotection in the real world and underproduction in the virtual world—are the major reasons why children born after 1995 became the anxious generation.”

Finally, here are his four foundational recommendations, spelled out in his book:

- No smartphones before high school. Parents should delay children’s entry into round-the-clock internet access by giving only basic phones (phones with limited apps and no internet browser) before ninth grade (roughly age 14).

- No social media before 16. Let kids get through the most vulnerable period of brain development before connecting them to a firehose of social comparison and algorithmically chosen influencers.

- Phone-free schools. In all schools from elementary through high school, students should store their phones, smartwatches, and any other personal devices that can send or receive texts in phone lockers or locked pouches during the school day. That is the only way to free up their attention for each other and for their teachers.

- Far more unsupervised play and childhood independence. That’s the way children naturally develop social skills, overcome anxiety, and become self-governing young adults.

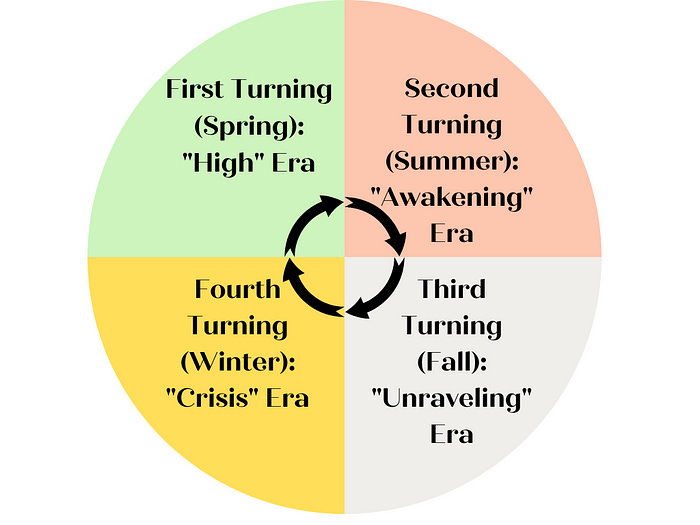

The Fourth Turning

As some historians might suggest, maybe we are indeed in the fourth turning, denoting a period of crisis in our culture. If so, we must become bridge-makers, work towards a new era, and provide guidance.

Based on William Strauss and Neil Howe’s book, The Fourth Turning. Image from here. The four turnings, or each saeculumm, comprise history’s seasonal rhythm of growth, maturation, entropy, and destruction.

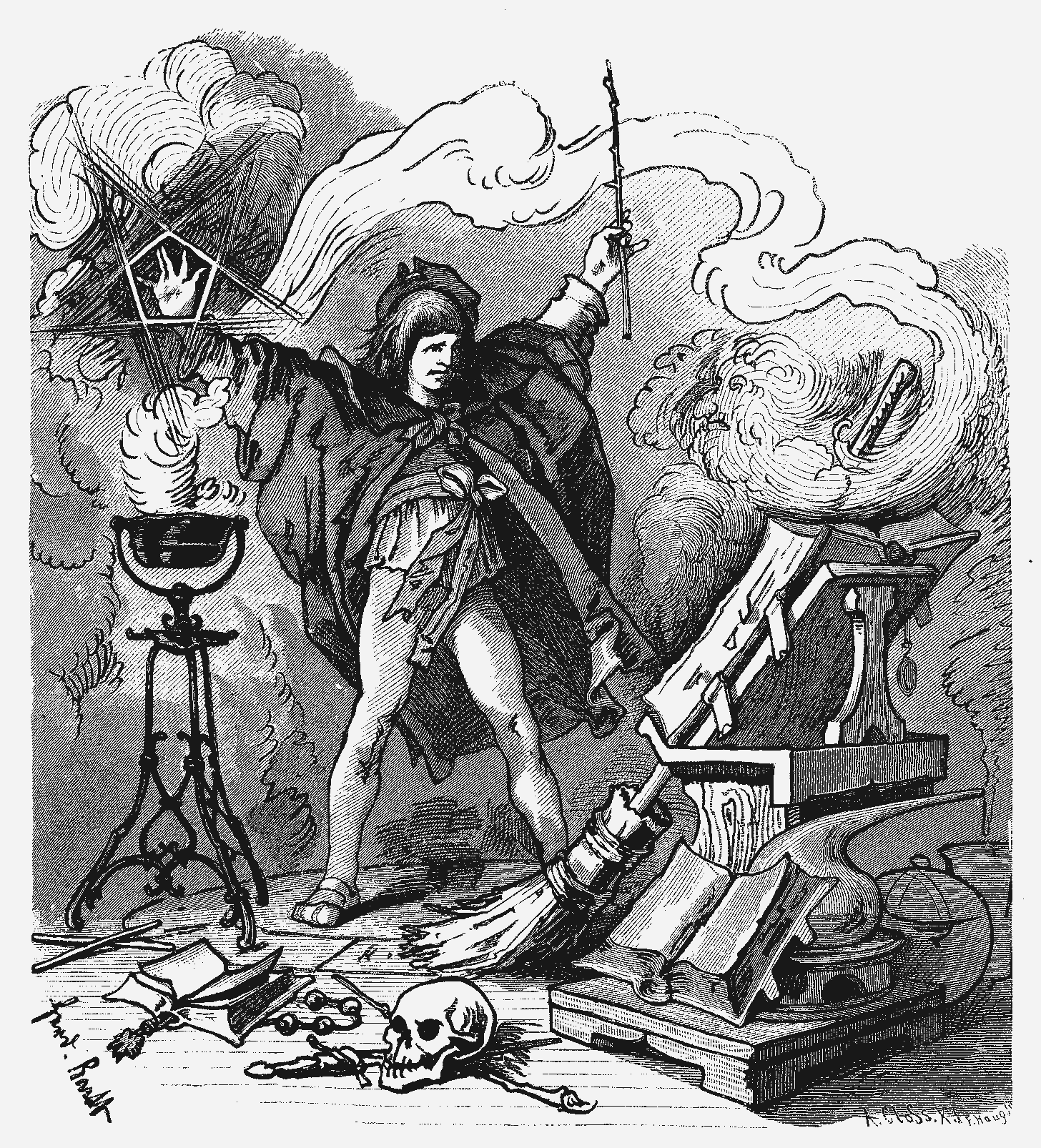

Recall the timeless myth of the Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Every young apprentice needs the guidance of an elder, otherwise, things will go out of control. Think of the enthusiastic kung fu kid who thinks he’s ready, but must undergo trials. Meanwhile, he is asked by the Master to wash the windows. Wax on, wax off.2

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Tired of fetching water by pail while the sorcerer was out, the apprentice enchants a broom to do the work for him, using magic in which he is not fully trained. The floor is soon awash with water, and the apprentice realises that he cannot stop the broom because he does not know the magic required to do so.

Whether you are a mental health professional, teacher, parent or grandparent, I hope you will pay attention to

Jonathan Haidt and colleagues’ work (e.g.,

Jean M. Twenge ). They might just be our guides, as we guide our youths3 to subvert against tyrannical tech, to rebel against the Algorithm, so as to find ourselves again in this Arc of Life, a true life that is waiting for you.

If you are reading The Anxious Generation, I would love to hear your reactions and reflections to the Introductory and Chapters and 2. I would like to discover and learn with you along the way. Leave in the comments below.

p/s: Have a Good Friday and Happy Easter.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Hi Daryl. Thank you so much for everything- I come away with energy to re-focus when I read your work.

The link to your evergreen case note template isn’t working- are you still making that available?

I’d love to have a copy please.

Hi Helen, sorry about this. we will fix this. Meanwhile, pls use this link: https://darylchow.ck.page/7f43b55c97