Try this little thought experiment: Take a piece of paper, and in the next 2-3mins, in no more than 2-3 paragraphs, write down your philosophy of what guides you in therapy.

Most of us will struggle with this at first. But don’t give up. Park some time in the coming days to articulate your guiding philosophy in therapy, and come back to this post.

Let’s try another shorter thought experiment: Make up a title for a book on psychotherapy that you would go immediately to a bookstore to purchase.[1]

Why am I suggesting for you to play around with the above exercises? Because you have to create your own first principles to guide what you do in therapy. In the previous blogpost, I highlighted the importance of developing first principles before methods. While it is perfectly fine to borrow ideas or get inspired from different schools of thought, there comes a stage in your professional development that you need to develop a guided and reliable way of working in therapy (This is especially crucial if you are a clinical supervisor, as you would need to impart your wisdom to other therapists).

We have some evidence that trying to model after another person doesn’t translate to improved performance.

In her last interview with Rich Simon, Virginia Satir was asked what she thought about neurolinguistic programming (NLP), which was modeled after her approach to therapy. Her response was, “I would not want to learn NLP, if you want to know the truth. I am not sure I could learn it”[2].

Unless you are a towering figure coupled with nurturing warmth like Satir, trying to mimic her will only take you so far. Even Carl Rogers was quoted to have said that “I’m not a Rogerian.”

Each individual’s therapeutic style is an uncharted territory. More than an issue of personal style or theoretical orientation, it is vital to go one more step further, and articulate your first principles that are the pillars of your therapy home.

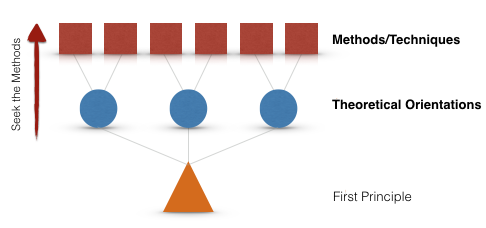

Too often we are taught a methodology and how to deliver a particular approach without a clear gasp of its first principles (See Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bottom-Up Approach

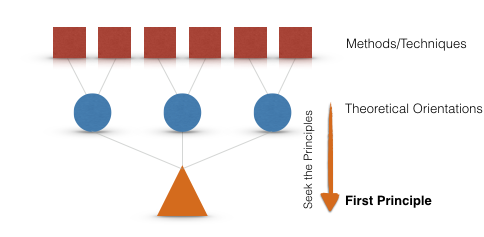

When we are trying to learn, we should be going the other way around. We should instead go down to the first principles of what informs the theoretical underpinnings and the methods and techniques involved in specific interventions (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Top-Down Approach

By reversing the process, we get to the operational level of first principles, we are then able to distill to the fundamental elements, and then choose whatever methods or approaches to deal with a particular situation.

The Three Ways

I propose three avenues that you can use to develop first principles in your clinical practice that relates to your native context:

- Challenging Situations;

- Mistakes, and

- Connecting with Mentors.

1. Challenging Situations:

- Comb through your work calendar, and call to mind the clients you’ve seen over the last 2-4 weeks;

- Identify which consisted of challenging or difficult situations;

- Classify them. Give the scenarios a name (i.e., ambivalent, challenging your credibility, client with no goals);

- In each of those situations that you’ve classified, what were the default guiding principles that informed the way you interacted with your client?

To get into the weeds, you might want to check out our Taxonomy for Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA)[3] to help you spot a variety of challenges that you might face within the therapy hour.

2. Mistakes:

Mistakes are a great way to develop sound principles of your own. Treat mistakes as puzzles to be solved.

Once you’ve parked your ego aside, and see a mistake as a moment for recalibration and deep learning, you can go, “what were the guiding principles that informed the way I interacted with this client?” Once you’ve worked backward to derive at your first principles, you can then go, “Okay. The next time when I’m faced with this type of situation, then I would do this…” This is where a new guiding first principle can emerge.

Here’s the truth about mistakes: It’s really hard not to take it personally. I made a big blunder just yesterday in one of the sessions. I’m still recovery from how silly I could be insensitive to a person’s background by my choice of words. Here’s the first principle I’ve gleaned from this painful experience:Prime Myself just before the session with key markers to watch out for. Reason: I can’t rely on my long term memory, and need the relevant information activated in my working memory. Why is this a first principle for me? Because it’s generalisable; this can be applied to many situations.

Keep this in mind (as I remind myself too): The key is not to ask yourself, “What”s wrong with me?” but rather, focus on “What can I learn from this situation?” Because we are so heavily involved in the therapeutic work, the final point matters a great deal.

3. Connecting with Mentors

Talk to your supervisors or your peers that you admire. (I wrote a previous post on this related topic, Specific Ways to Develop a Portfolio of Mentors. Do your best to dig a little deeper to understand the following: What are the first principles that organises this person’s thinking and approach, or even the suggestions that they gave you?

In the previous post, I listed the reasons why we need first principles. To recap, “First principles are GROUNDING IDEAS, not GROUND RULES. First principles are organised in a Form, not a Formula. A form gives you a rough guide on how to operate; a formula tells you a fixed rule on how you must operate.”

The Importance of Retrieval

Our craft matters less than our ability to ACCESS our craft.

By explicating our first principles, we not only become cognisant of them, we have now CHUNKED them into succinct statements that can guide us in the future, especially when we most need them in challenging situations (therapy is one profession that is not short of challenges). We love to ascribe to the term “reflective practice,” but reflection is of little use when we have nothing useful to feed back into our minds and feed forward into the future.

Write down your first principles. Put a date on your writing, be it on a notebook or a writing application (see previous post on the importance of writing stuff down, Develop Your Own Wealth of Learningsand Therapy Learnings: A Memorable Practice )

~~~

In my undergraduate years, I was lucky to be taught by psychologist Dr. Robert Closs. In our first lesson on Psychotherapy and Counselling, he put two of us behind a one-way mirror to observe the conversation. As I grew up as an very shy and introverted kid, by sheer force of will to counter my intuition, I raised my hands to give it a go. Due to the nerves, my memory of that event is a bit of a blur. What I remembered was the discussion after the exercise. Dr Closs asked the class, what made the conversation become alive? He provided the answer to his own question, “It’s because they were talking about their interests.”

Years later, though Dr Closs didn’t quite say it this way, but the principle that resonates in my mind years later was this: “Follow the Spark: People are interesting when you are interested. Go further by asking questions that convey your interest in the other person who is in front of you.” This is not just lip service, or about “staying curious”. This is a full intentional leaning in to learn more about the person, and to figure out what is life-giving, and what lights them up. This has guided me tremendously, especially in my first sessions

(NOTE: A forthcoming book is on the way with a chapter touching on this topic. The book is calledFirst Kiss: Undoing the Intake Model and Igniting Engagement in the First Session of Psychotherapy. It addresses the persisting issue that majority of clients dropping out after the first visit.)

I’d always remember this sign on Dr. Closs’s door.

“Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them… well, I have others.”

~ Groucho Marx

~~~

In the next post, I will be taking this idea of first principles another step further on how you can apply first principles prospectively in your clinical work. I’d discussed about The 5-Step Process for Deep and Accelerated Learning in Therapy.

Here’s a sneak peak this 5-Step Process:

I would love to hear your thoughts and comments about this post. What are some of your first principles that has guided you in your clinical practice so far?

Footnotes:

[1] This idea was taken from Bradford Keeney’s book, Improvisational Therapy.

[1] Simon, R. ( 1985). Life reaching out to life: An interview with Virginia Satir. Common Boundary, 3, 36—43.

[3] Email me (daryl@darylchow.com) to receive a copy of the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA). Thanks to the editors for pulling these books together, we touched on this briefly in two recent book chapters:

Chow, D. (2017). The practice and the practical: Pushing your clinical performance to the next level. Prescott, David S [Ed]; Maeschalck, Cynthia L [Ed]; Miller, Scott D [Ed] (2017) Feedback-informed treatment in clinical practice: Reaching for excellence (pp 323-355) x, 368 pp Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; US, 323-355.

Miller, S. D., Hubble, M., & Chow, D. (2017). Professional development: An Oxymoron? In T. Rousmaniere, R. K. Goodyear, S. D. Miller, & B. Wampold (Eds.), The Cycle of Excellence: Using Deliberate Practice in Supervision, Training, and Independent Practice (pp. 23-47). River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA: Wiley Press.

I am a student in Jeff Chang’s online clinical supervision course and have beennso grateful that your work has been introduced to me, especially via an illustrated talk. I am a very experienced counsellor ( over 35 years) but have never been chalkenged in such a clear and foundational way. I really need these tools!

Right now I am working on the question of my own First Principles, and I would like to undertake the deliberate practice actibities approach— I like the ideas of self-study and experimentation.

Hi Jane. Thanks for your comment. Nothing more invigorating that to be challenged and pushed to our growth edge. In turn, this makes us re-look at our fundamental principles.

Hi Jeff,

I am a new reader and I am curious if maybe I missed something. First of all, I love the concept (and praxis) of principles and I think it is an important key.

I also really appreciate that you put that quote from V Satir as it is incredibly difficult to “be” someone else like a mentor or, even harder, someone you never met whose model you are trying to learn/implement.

Finally – my question…. from what I gather, you seem to imply there isn’t much value in learning theories and that focusing on developing principles first is more important. Did I get that correctly?

At ay rate, I find value in both. There is something special about deeply exploring the theories of close or distant mentors in developing one’s style and principles, I think. I see those two “organizational” charts as being interactive and fluid – which means to me, it could be added to the lovely “5 step” diagram. Maybe it is implied that after all that schooling and internship stuff that we have already laid the groundwork, etc. and we don’t need to go back to the theory stage– but I have found so much value in finding theories that align with my principles that I wanted to ask you about it.

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and possibly clearing up my confusion.

I really appreciate the work you do!

Hi Melissa,

Thanks for your comment.

T

heories explain. But principles guide.

Theories help you understand based on what is patterns are known in the past. Theories are descriptive.

Principles, on the other hand, acts like a compass on where you should go and what you should do next. Principles are _prescriptive_

I believe I addressed this in one of the evergreen missives that goes out to FPD subscribers darylchow.substack.com