Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 26 Jul. 2024

Books are a uniquely portable magic. — Stephen King

I loved the smell and ambience of libraries. The smell of aging paper and quiet hushes bring about a comforting feeling. This was somewhat strange to me as I was not at all a bookworm as a kid. Visiting a library was rarely on the cards as a place of interest. Nonetheless, I found myself visiting the library quite a bit during my undergraduate period.

I soon found the magic of libraries. When you do a Google search, you are using a tight lens based on your search query. When you do a library search, you are using a wide lens and you are essentially just exploring. I stumbled upon a book called Escape from Babel. Its subtitle grabbed my attention: “Toward a Unifying Language for Psychotherapy Practice.”

On the shelf, was another book, “Psychotherapy with Impossible Cases.” I did what any student did with a book that they really liked. I photocopied the entire two books. I couldn’t afford it, and I also had an inkling that I would be revisiting these books.

Coincidentally, my lecturer for the counselling module, Robert Closs mentioned the work of Scott Miller, Barry Duncan and Mark Hubble. Based on the existing evidence, he was cautioning us about the temptation of joining the cults of various therapeutic approaches and in actuality, very little evidence suggests that one model is better than the other. I was intrigued, as I had one foot in a “cult” thinking regarding a specific approach to therapy at that time.

Then in 2004, when I got back to Singapore to do my Masters, my dear friend Shannen said to me, “Oei, I think you’d like this book.” She turned to the front page and showed me. One of the co-authors signed her book. I asked to borrow it. I have to admit, I only returned it after she had asked for it back twice.

That book was Heroic Client.

I couldn’t believe what I was reading, and why the information presented in the book was not taught in schools as common knowledge.

I made a decision to apply some of the learnings from Heroic Client when I moved from working as a youth worker to a psychologist at a psychiatric unit in a hospital. I started to measure my outcomes and engagement levels with each client at every session. This practice was previously called, Client-Directed, Outcome-Informed (CDOI).

It was a clunky process for me. I had no one to turn to. Strangely, the hospital that I was working in weren’t bothered nor interested in the way I was practicing. Initially, I was number-fixated. Every little minute change in a sub-scale, I harped with my clients about what that meant. Thankfully, after watching my sessions, my clinic supervisor had good sense to remind me not to lose the forest for the trees. These measures became less of an assessment tool, and more of a conversational tool for me.

RELATED:

I moved to another psychiatric hospital, and continued my practice of monitoring outcomes and engagement. I got guidance from people like psychologist in private practice, Jason Seidel from Colorado. I joined an email listserv to connect with like-minded people. That was gold for me. Plus the fact that the authors of these life-changing books were also replying to the threads; this was such a treat for me. I thought to myself, Man… if I ever become an author, I want to be as open and communicative as they are.

During my masters programme, I was again surprised that no one had taught anything based on what I was learning. I put my head down and continued to do my thing, reminding myself that there were a small group of people in the world who are also on the same page

An Article That Led to a Turning Point

A few years later, I got the Nov/Dec 2007 issue of the Psychotherapy Networker Magazine in my (snail) mailbox. It was the only magazine I had subscribed to. I probably could afford to pay for this now that I have a full-time job.

Who would have thought that a single article in that issue became a turning point in my life.

The article was called Supershrinks: What’s the Secret to Their Success? written by Scott Miller, Mark Hubble, Barry Duncan. The same people whose previous books turned my world upside down.

I made contact with Scott Miller. First, I couldn’t believe he would reply my emails. Second, I couldn’t believe how open he was to have a discussion about his ideas, and how encouraging he was of my incoherent thoughts. Plus, he had a knack of making me sound smarter than I was. Our discussions continued over Skype.1

I got married in 2009. During our honeymoon in New Zealand, we went to an internet cafe to retrieve our emails, and I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I got a scholarship to pursue a Ph.D. Now, you have to understand, people get scholarships, not me! I had nearly flunked my primary school leaving exams (PSLE), was in a placed in a “normal”2 stream during secondary school (which meant that I had to take 5 years and not 4), and I nearly dropped out my tertiary education in Polytechnic.

I felt like I had “tricked” the university.

RELATED:

Thankfully, my wife had more faith in me than I did, and she was up for an adventure to uproot and move countries. The invitation for the doctorate was in Western Australia. I had first met my wife in Queensland, and she thought, “Why not?” We packed our bags the next year and headed down under.

Go to the Source

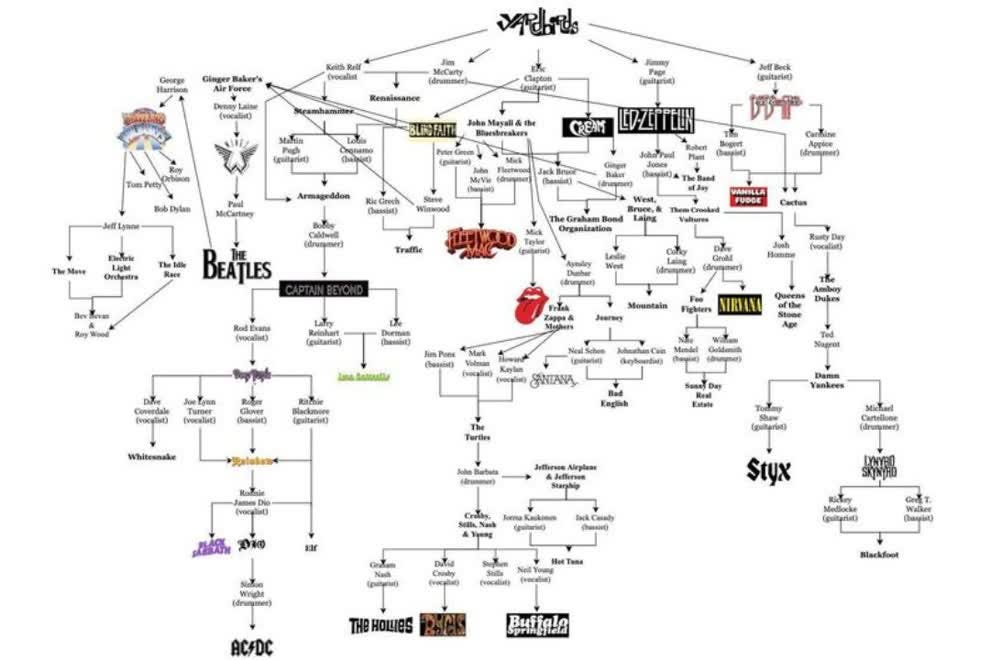

In my youth, I had adopted a principle that I applied to my love for music: “Go to the Source.” This meant that any time I hear a musician that I really liked, I would hunt down who influenced them. Much of the detective work led to the greats, e.g., The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix. And things become more interesting when you take “Go to the source” a little further (e.g., Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Little Richard, Elvis Presley).

I applied the same principle to my own learning process. I pursued all of the references that were in the books and articles that I read. It was painful and labourious. But it also felt like I was mining for gold.

A particular researcher’s naming kept popping up in every other journal article I was reading. His name was Bruce Wampold. My wife was a little perturbed that his book, the first edition of The Great Psychotherapy Debate, came with me wherever we went, even on vacations.

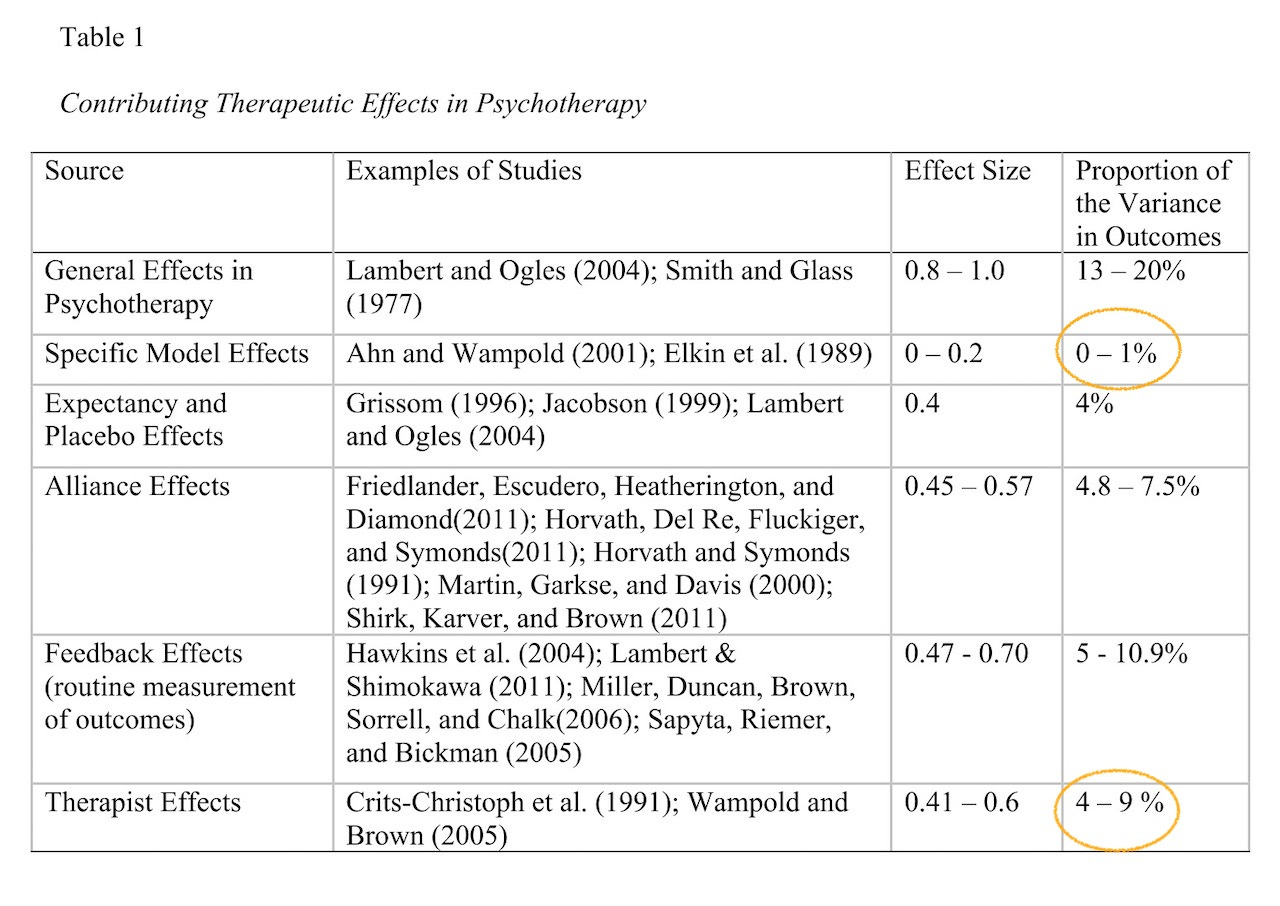

There was so much that I didn’t understand. Take for example, how was it possible some studies found superiority in outcomes comparing one treatment approach to another, while other studies seem to find that there were no differences? I later learned from Wampold and colleagues study that one of the fatal flaws in research design is when researchers fail to account for who the treatment provider was, (i.e., therapists were treated as “error variances” in the statistical analyses), treatment differences show up3.

But when you account for who the therapist was (i.e., nested design. see above), treatment differences disappear. In other words, 5-9% of the differences in outcomes were due to therapist effects, and 0-1% of outcomes were due to treatment effects.4

Between 2010 to 2014, I devoted my time to learning as much as I can about our field in psychotherapy5 and begin the research that I had proposed. The pitch was simple: to study the development and practices of highly effective therapists. The University had invited me and some other students to meet-and-greet with Singapore’s Minister for Foreign Affairs, Brigadier-general George Yeo at Curtin University, Australia. He asked me what I was researching. I told him. He looked surprised, and he asked, “Hasn’t this been studied before?” Nope.

There were studies that looked at “master” therapists, but there was no clear evidence to suggest that these were indeed highly effective therapists; there were largely peer-nominated therapists.

Inspired by Scott’s and colleagues article, I called the project: The Study of Supershrinks.

I had one problem though: How was I going to get any data from existing therapists who have been systematically monitoring outcomes? Plus, even if I could find therapists who measured their outcomes, would they be interested in participating in this study?

Bill Andrews, former dentist turned therapist came to the rescue. He had been involved in Practice Research Network (PRN) in the UK and linked me up. I don’t think there are enough beers that I could buy him to express my gratitude.

We designed the study protocol, largely inspired by the work of Swedish psychologist, the late K. Anders Ericsson, which Scott wrote about in his 2007 article. Scott and I met Ericsson in Kansas City in 2010 and he provided much-needed guidance to the project (see this post).

I thought I would take 2.5 years to finish the study, but it took 4 years (Planning fallacy 101). The money ran out. Given our visas, my wife and I were limited by the hours we could work per week. At the third year in 2013, we were expecting our first child. Yikes. Money was running dry, scholarship and visa was ending, and our baby was about to pop.

Eventually, we pulled it off. The thesis was done in 2014, the first study on deliberate practice in psychotherapy was published. We flew back to Singapore. Our first daughter, Amelia Chow is born.

Here’s a link to the thesis if you are interested.

And here’s the link to the published article. (Naturally, much details were left out in the peer-review article compared to the thesis.)

My Takeaways:

I hadn’t planned to write this backstory. I wanted to address and clarify some misunderstandings about deliberate practice based on our 2014 study but I felt that this background would serve as a foundation.6 I will do so in the next issue of Frontiers Friday.

But here are three things that stand out from looking back:

- Standing on the shoulders of giants: If it wasn’t for people like Scott Miller, I wouldn’t be able to do this. If it wasn’t for people like Bruce Wampold, K. Anders Ericsson, etc, we wouldn’t have the foundation to build this.

- Be with people who have more faith in you than you do: Looking back, I’m struck by the fact that at every turning point, I have had people who thought more of me that I had of myself. Even as I write this, I feel moved with gratitude. These people have been my guiding lights.

We all need guiding lights. I worry about many people who don’t have such people in their lives. When we lack a guiding light, we fall to our lower desires. - Direct your own learning: School tells you what to learn. In life, you have to figure out what to learn. The real fun is when you decide what is worth learning, and you run after loves.

In defence of books:

Books are not just books. If thought was a monologue, books are a form dialogue. If you engage with a book, it is like having a deep conversation with someone who has thought about a specific topic for a very long time. As Neil Postman would put it, the act of reading a book is the best example of distance learning ever invented.

I’m deeply thankful to all the books I’ve read, and the people who took the time to write them.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments