Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 24 May 2024

Note:

If you have missed the previous week’s missive, feel free to go to FF184 to download your free copy of the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice (TDPA) worksheet, plus the googlesheet version, which helps you track your progress and guide your focus over time.

Basketball

6/10.

Phew. That’s what I scored at the free throw line.

For as long as I can remember, I have played basketball.

If I had a dollar, I would use 80 cents to buy a can of Coke, and 20 cents for a tiny box of Nutella. My friends and I would sit at a void deck on our skateboards and finish that 4.5 tiny scoops of Nutella, and then go shoot some hoops.

If I wasn’t at the basketball courts, I would be at a friend’s house playing NBA on his Sega set. If not, I was watching LA Lakers and Chicago Bulls on television. And when I was in the mood, I would be at home shooting at the miniature rim, with the 4 walls as my imaginary team mates to alley-oop to me for a slam dunk.

In my teens, I wasn’t the best at B ball, but I was good enough. I was short compared to the others, but I thought if I kept playing, I would grow taller. I did eventually grow in height (I think it was the genes, not the exercise), and I did get better.

Until I didn’t.

More than 30 years ago, my average free throw was 6 out of 10.

Actually, I thought it was not bad. I mean, I’m better than Shaquille O’Neal, one the most dominant players in NBA history, who had a career free throw percentage of 52.7% (that’s why the other teams loved sending him to the foul line).

Here is Shaq’s comment:

Me shooting 40% at he foul line is just God’s way to say nobody’s perfect.

Compared to Michael Jordan, his career free throw percentage was 83.5%. That’s insane.

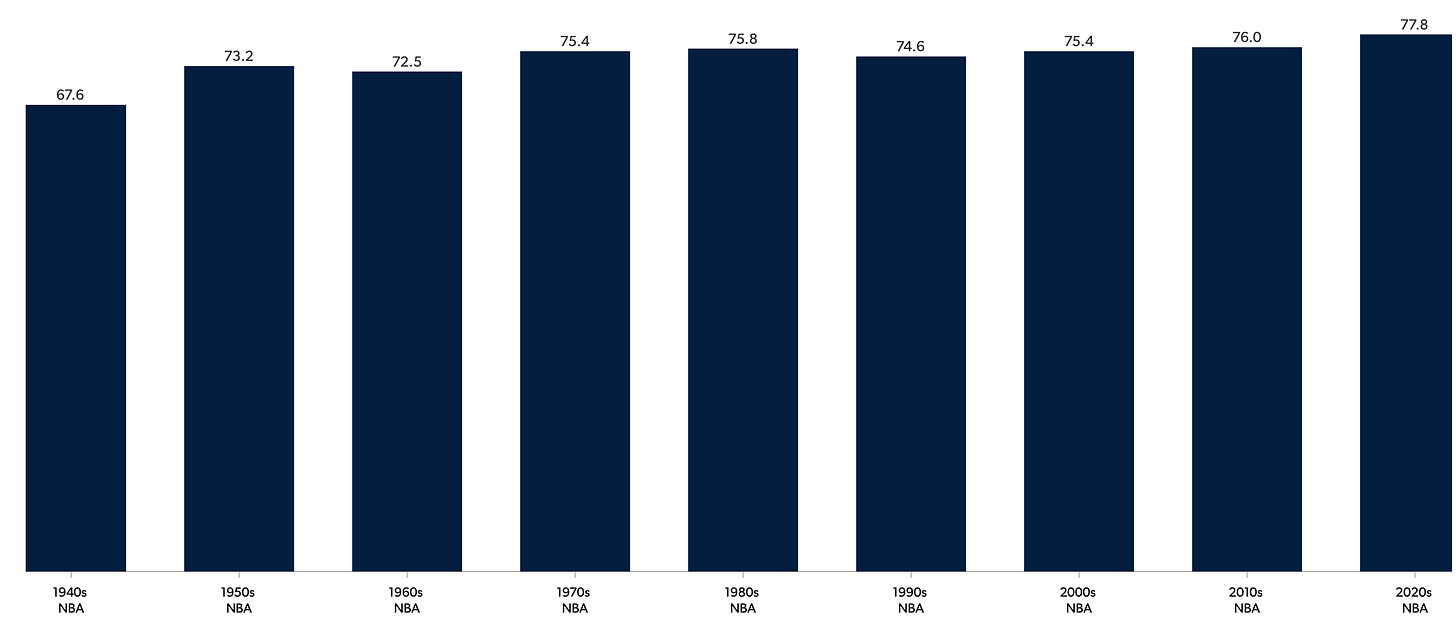

What was the average free throw percentage in NBA for 2020s? Approximately 77.8%.

Wait, what about the the free throw percentage in the NBA across time? Did it change, or was it stable?

As I had not been devotedly following the NBA since the early 2000s, this is somewhat shocking to me. The statistics above were not just based on a single individual player or a specific team; they were averaged across the board.

And its not just the free throws.

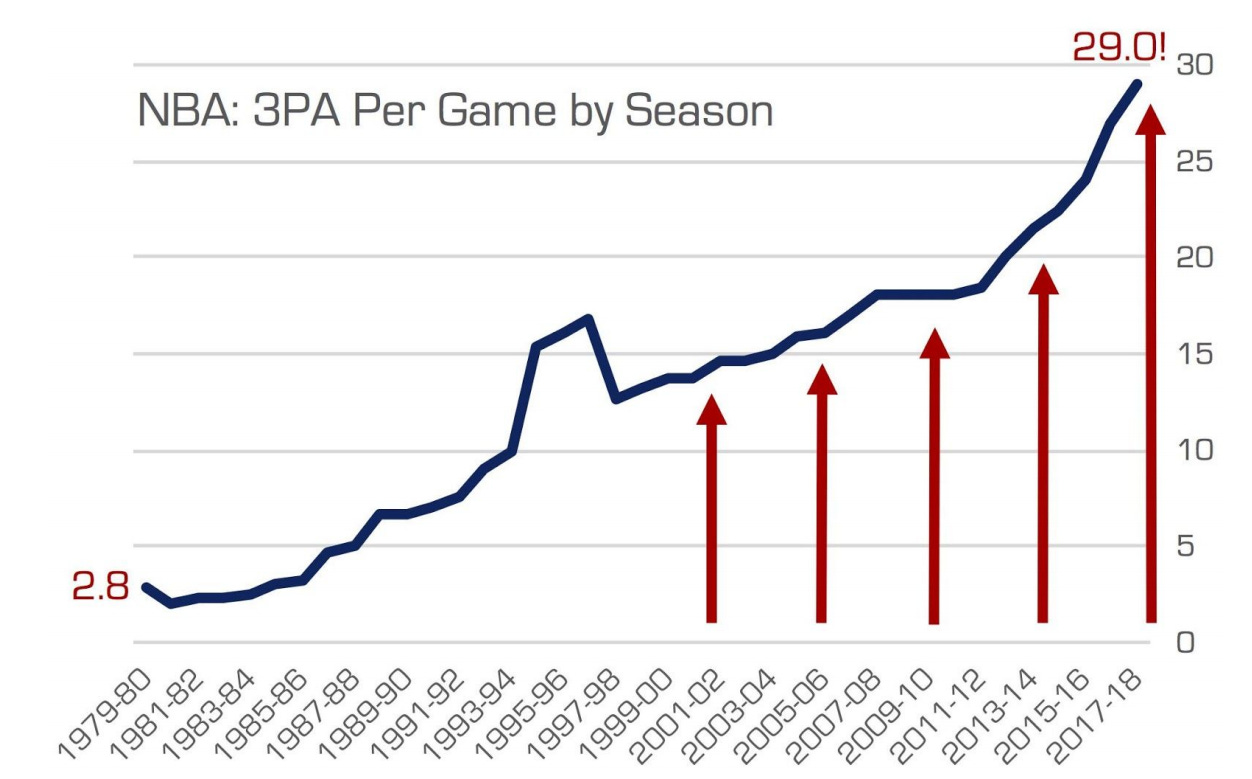

Shots from 3-pointer line have dramatically increased over time.

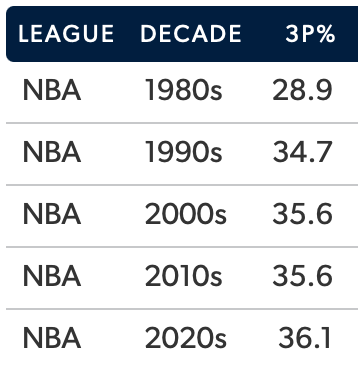

Not only the attempts at 3-pointers have increased, the percentage of shots from the 3-point line have also improved dramatically . Since the three-point line was introduced in 1979, take a look at the stats from the 1980’s til today.

Critics have been suggesting that this trend has brought the game to a turning point, potentially making the sport boring—because everyone is aiming from afar to get the extra point.

Free Throw

After dropping off the kids to school, I thought it might be good to go to the court to clear my head and shoot some hoops. It was a hectic day at the practice yesterday.

I mucked around for a little while… and I couldn’t help my thinking brain, and I thought to myself, if I were to tweak ONE aspect to improve my shots, what would that be?

Just for fun—and feeling a little unfit at 45 and sedentary living—I thought I would slow down on the running and see what’s my shooting accuracy at the free throw line. Indeed, I scored 6/10. And just to recap, that was my average in the past.

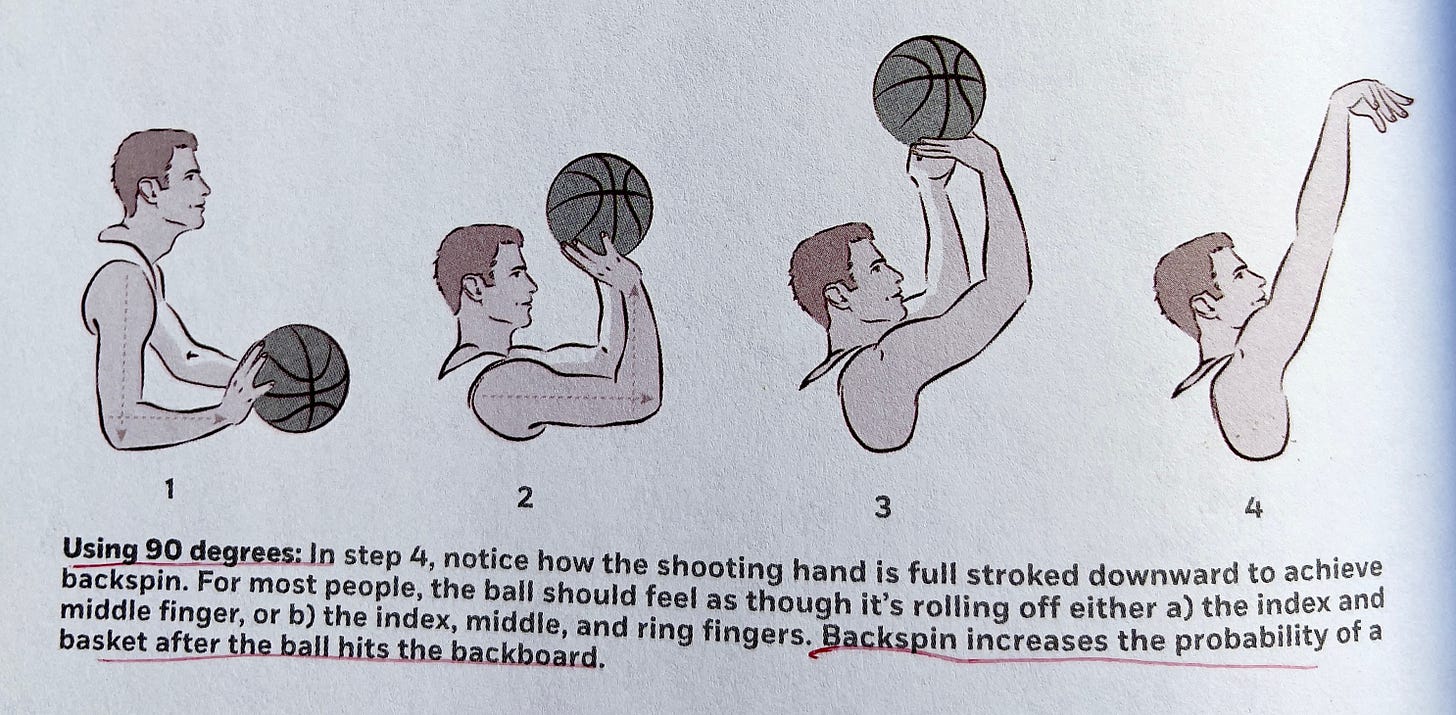

Then I recalled some year ago from Tim Ferriss’ book, The 4-Hour Chef (it’s not really about cooking), in a chapter, he talked about how to improve one’s shooting at basketball.

Ferris wrote,

After each shot, freeze your arms and spot-check your form.

I started to pay close attention to the feeling of the ball leaving my shooting hand and finger tips as I flicked to a backspin. Given what I’ve learned and past advice from better players, this is something that I can work on to that can improve my accuracy.

I got back to the free throw line and took my second set of 10 shots. I thought to myself, this is going to work…

I scored 4/10.

Argh.

I meandered around for another few minutes, and then got back to my third and final set of free throws, and committed to focusing on the feeling ball leaving my hand and fingertips. Here’s how it played out, shot-by-shot:

0-1 (missed)

0-2 (missed)

0-3 (missed)

0-4 (missed)

I’m now contemplating packing up and going home.

I thought to myself, Man, this isn’t even a real game… no one’s pressuring me or booing at me in the crowd like Shaq.

Letting go of the scoreboard in my head, I stayed focused on what I was supposed to work on. The flicking feeling of the ball leaving my hand.

1-5 (in)

2-6 (in)

3-7 (in)

4-8 (in)

At this point, it feels like magic! But I had to remind myself, forget about whether the ball goes into the net or not.

5-9 (in)

5-10 (out).

Not exactly a happy ending.

In summary, here’s the free throw score for today,

1st set: 6/10

2nd set: 4/10

3rd set: 5/10.

Should I just stop working on the form as the ball leaves my hands and fingers?

Best and Worst Decisions

Here’s a thought experiment:

- Think of a best decision that you’ve made last year.

- Next, think of a worse decision that you’ve made last year.

Write your responses to both before you proceed.

As Annie Duke stated in her book, How to Decide, most of us would answer the two questions based more on the outcome of the decision rather than the decision process itself.

As a professional poker player, Duke said in her previous book, Thinking in Bets,

Life is not like chess. Chess contains no hidden information and very little luck.

Life is more like poker. You could make the smartest, most careful decision and still have it blow up in your face.

You might recall from the previous article about the difference between a kind and wicked environment. Chess is more of a kinder environment that poker.

In a wicked environment, we can’t draw a tight-conclusion between decisions and outcomes. “When a decision doesn’t work out,” said Annie Duke, “Don’t treat that result as if it were an inevitable consequence rather than a probabilistic one. Don’t focus only on the poor outcome (emphasis mine).”

Here’s a visualisation to help us think this through:

It’s easy to think of examples that fall in the Good-Good, and Bad-Bad quadrants (e.g., I study for the test, and I got good results. I didn’t study for the test, and I failed).

However, it’s not quite as intuitive to think of the other two quadrants, Bad Decision-Good Outcome and Good Decision-Bad Outcome scenarios.

Bad Decision-Good Outcome: You had too much to drink and you still decided to drive back home (bad decision). Thankfully, you got home safe and sound. There were no accidents—as far as you know. (good outcome).

Good Decision-Bad Outcome: You did all the research and background checks about the new workplace you were joining and the new role is aligned with your values (good decision). However, your boss left 2 months later and the replacement is a tyrant from hell (bad outcome).

Making Good Decisions

This has ramifications of how you decide what to work on in your professional development as a psychotherapist.

Trying to improve outcomes alone is not going to get you very far.

We need to first understand what actually has leverage on improving outcomes.

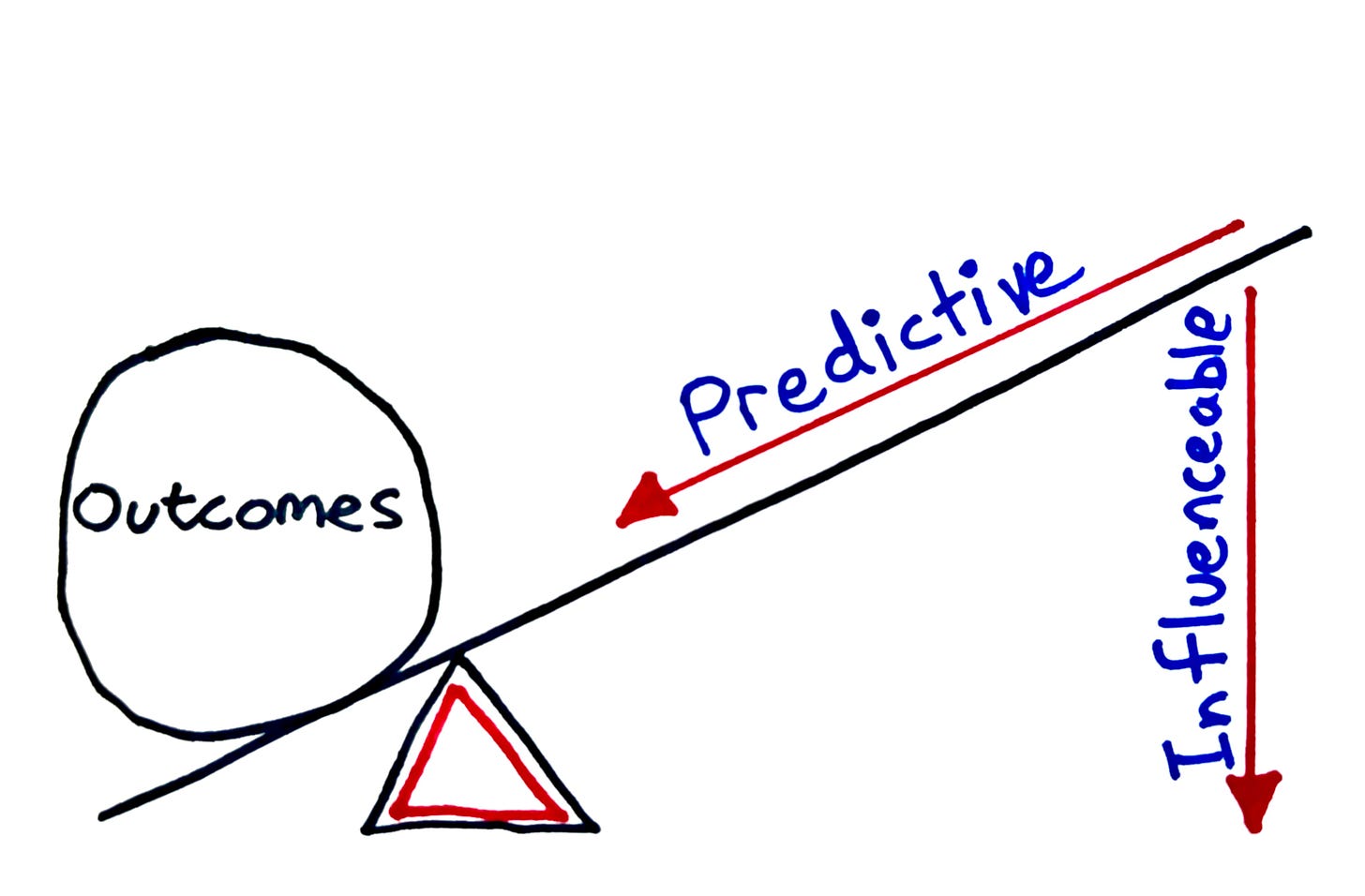

And then, we need to take a step back and ask, what are some things that predict outcomes, plus, something that you can work on, taking one step further than where you are now i.e, your baseline.

We need to know what is generally predictive, as well as what is specifically predictive of impacting your outcomes.

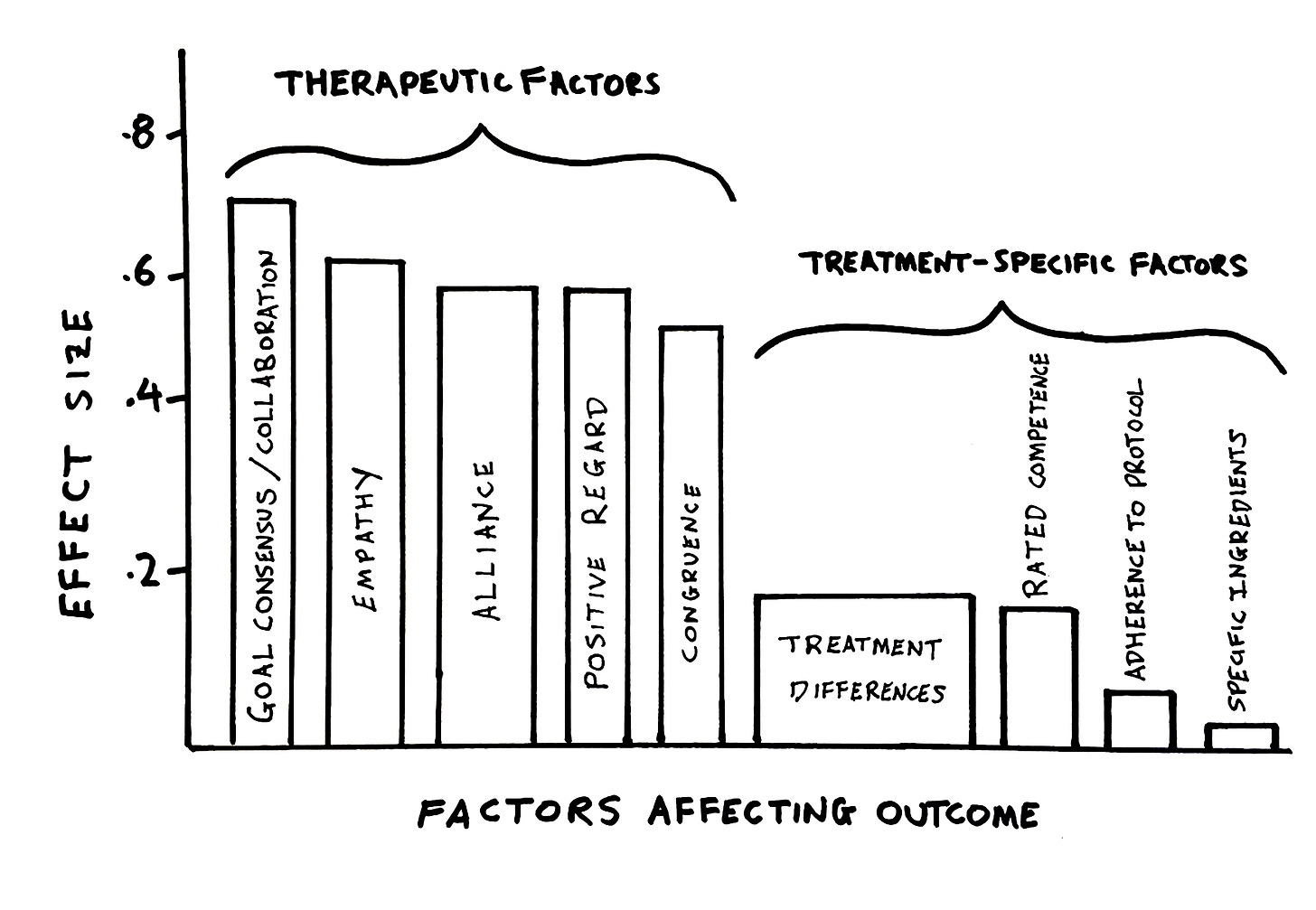

Here’s what we know from the psychotherapy literature:

Lots more studies have been done on treatment specific factors (i.e., thickness of the bar), compared to Empathy and Goal consensus, which has a higher yield on moving the needle on outcomes.

But the real question is: what is something you need to work on?

Archimedes said,

Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.

Richard Rohr takes this one step further:

(Yes) you must have both “a lever and a place to stand” before you can move the world. The educated and sophisticated Western person today has many levers, but almost no solid place on which to stand.

To develop a firm foundation, develop a baseline of how you are doing. Only by examining your localised aggregated outcome data—not just based on the evidence of other studies—coupled with a clarity of “how-you-do-what-you” (i.e., the decisions you make in and out of sessions), then you could start to get a sense of what is something that you can influence and leverage the fulcrum.

Outcome vs. System Mindset

Physicist Safi Bahcall echoes Annie Duke’s idea on “resulting.” In Loonshots: How to Nurture The Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries, he made the distinction between Level 1 Strategy of Outcome Mindset, and Level 2 Strategy of System Mindset.

The key differences between outcome and system mindset is this:

- Outcome Mindset targets specific results, while System Mindset focuses on the processes and structures that generate those results.

- Outcome Mindset is goal-oriented and often short-term, whereas System Mindset is process-oriented and long-term.

One of the examples Bahcall gave was this:

You can analyze why you argued with your spouse. It was, let’s say, your comment about your spouse’s driving. but you may improve marital relations even more if you understand the process by which you decided it was a good idea to offer that comment.

Safi Bahcall is no couples therapist, but this makes sense.

Bahcall added,

System mindset means carefully examining the quality of decisions, not just the quality of the outcome (emphasis mine).

How does this relate to the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA) Worksheet?

Pulling this together from basketball to therapy, the ideas about Decision vs. Outcome, and what we can leverage to improve the outcomes for our clients, here are some takeaways:

- Disentangle Decision and Outcome in the short term:

If you came to a position where you have decided to work on a specific area as identified from the TDPA, let’s say it is to improve your ability to develop an effective focus, don’t expect the outcomes to follow immediately in the short term. What you do automatically will be disrupted (for a good reason). - Perspective:

Get inputs from others who can make sense of your outcome, as well as someone who has reviewed how you conduct sessions. See if they agreed or disagree with your decision on what you are going to focus on.

Different seasons have different needs. This has to be also tied to your growth edge. - Connect the Dots:

Keep track on what you are working on and how it influences your outcome in the long-run (use the spreadsheet version of the TDPA). Depending on your caseload, review this on a 6-monthly or annual basis. Crucially, take stock of your decisions and development.

Basketball Redux

I have no plans to play basketball at a higher level (nor do I have the ability and fitness level—maybe I should improve my cardio first). But, for the sake of it, I’m going to try to see if I can improve my shots from 6/10 to 7/10, on a consistent basis.

And as most of you are on this life-long project, I’d keep working on the craft of therapy.

I’m rooting for you.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments