Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 02 Aug. 2024

Introduction

“I come from the land down under!” yells BMX freestyle cyclist Natalya Diehm, She is the first Australian woman to claim a medal in any international freestyle BMX event. Diehm told the reporter that she had the song, “Down Under”1 on repeat for the last 72 hours before the competition, lead to her claim of the bronze medal.

I’ve dropped my older kid to school. I’m back at my desk. I’m sitting with my winter puffy jacket on, and a coffee and water at hand, feeling moved by gratitude for being in the land of Australia. I remind myself to place the hand on the soil and give thanks.

Tempted to watch more Olympics. But the annoyance of not getting this writing done outweighs the pleasure of watching the games.

Last week, I gave the backstory and the turning points that led to my study of highly effective therapists.

Today, I want to address some findings that went under the radar about the Supershrinks study. There are also some misunderstandings about this study published about a decade ago. I hope to address them.

“DP = time spent” is a misleading conclusion

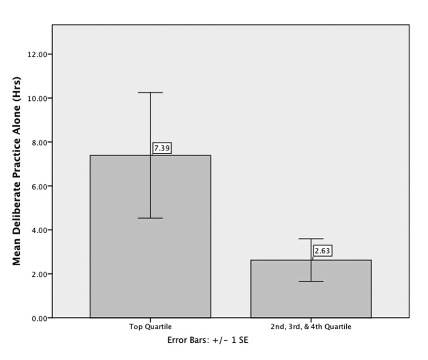

Most readers would know that the main finding from the study was that the amount of time spent in solitary practice targeted at improving one’s therapeutic skills was a significant predictor of client outcomes.

To me, this wasn’t the most significant finding. We will get to that shortly.

A decade ago, we found with this result in our analysis, which was similar to other professional domains. Not earth shattering news to say that time spent on improving matters.

However, this was not the working definition of deliberate practice we concluded with. The Supershrinks study2 was a discovery oriented study, modelled after Ericssson and colleagues (e.g., 1993) study design as well as others in the expertise and expert performance literature.

Given that there weren’t any previous studies done on DP in psychotherapy, we leaned heavily on study protocols outside of our field. One of the indicators, used in the study of expertise, was the amount of time spent (e.g., Charness, Tuffiash, Krampe, Reingold, & Vasyukova, 2005; Ericsson et al., 1993), which was why time spent in deliberate practice alone was added as one of the items in the research.

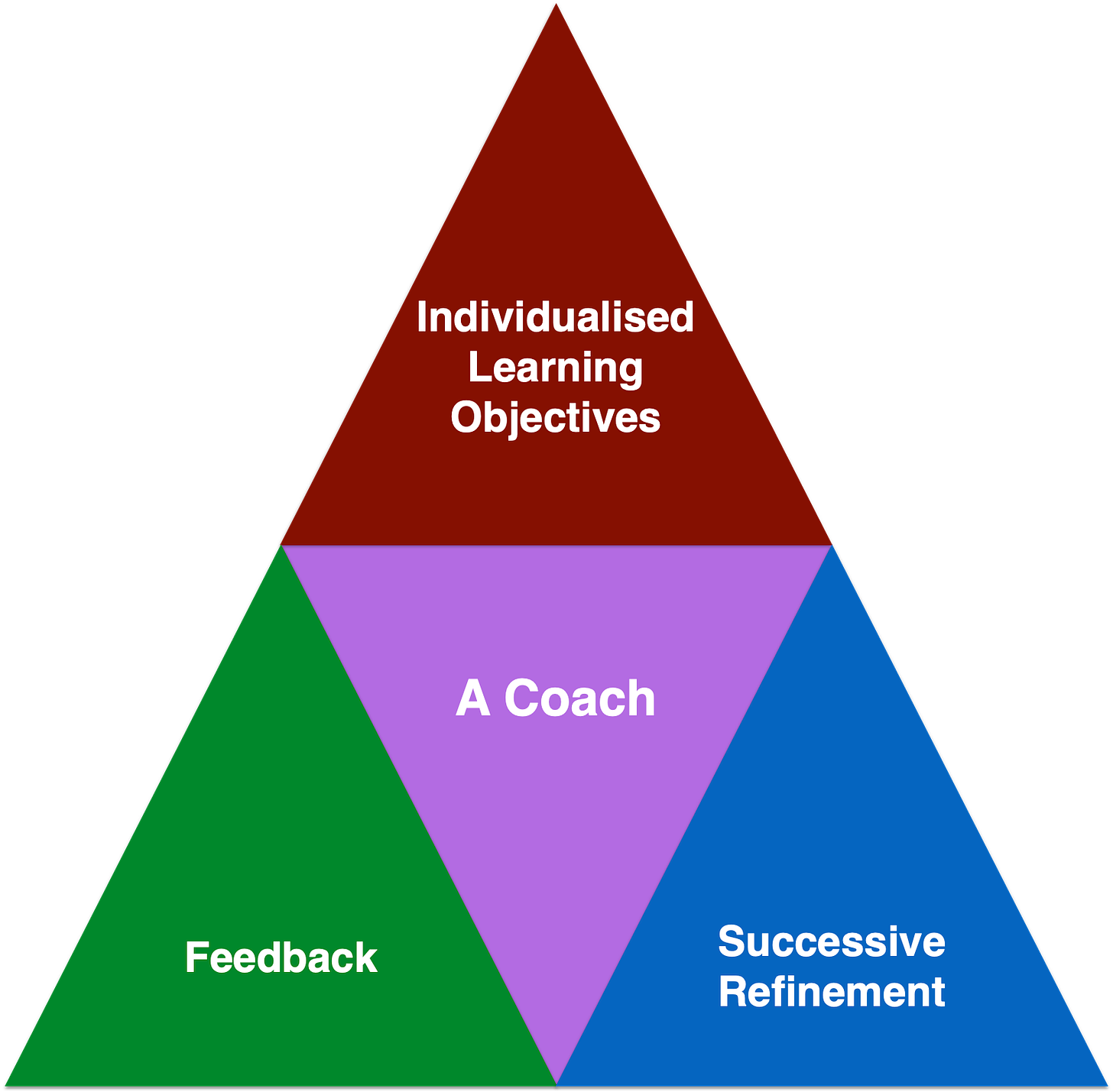

Since then, my colleagues and I further elaborated our working definition of DP in two papers3 and in our book, Better Results.

RELATED:

We said,

Time spent in a learning activity cannot be regarded as deliberately practicing the activity.

What the Study Didn’t Set Out to Do

We did not set out to see if any specific activities related with performance.

As mentioned, the aim of the original study was to initiate the first empirical examination of deliberate practice in psychotherapy, if we could glean knowledge from other fields in the development of expertise and expert performance and deliberate practice.

Even if any of the activities ended up as a signifiant predictor of performance, it would be erroneous to say that this is the activity to “DP” on.

Depending on a therapist’s professional development stage and their zone of proximal development (ZPD, Vygotsky 1978), it is critical to figure out what to one has to work on that has leverage on their outcome (Miller, Hubble, Chow, 2020) before the “how,” based on their existing baseline performance.

What do we do when one starts an exploration? Start wide.

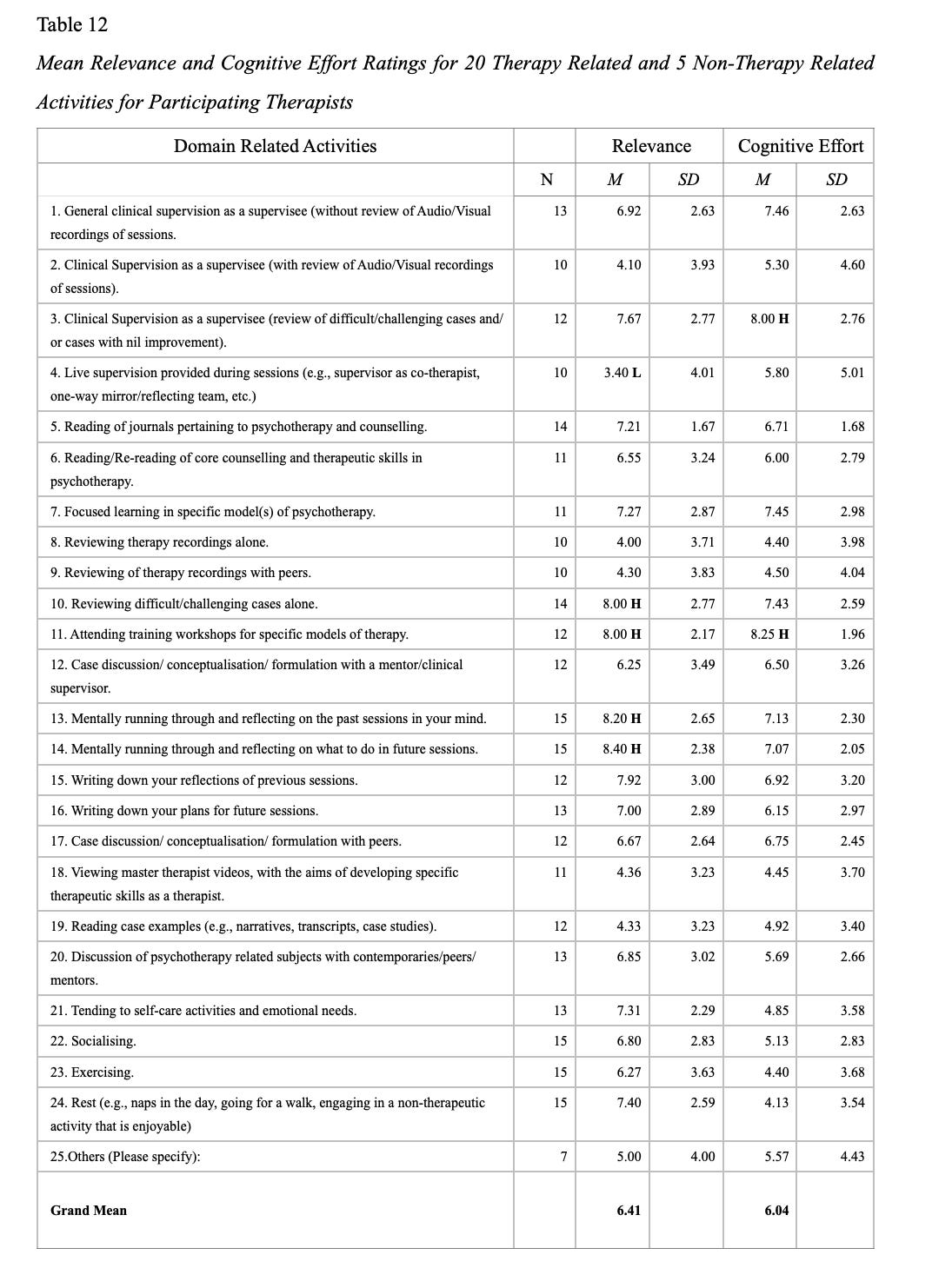

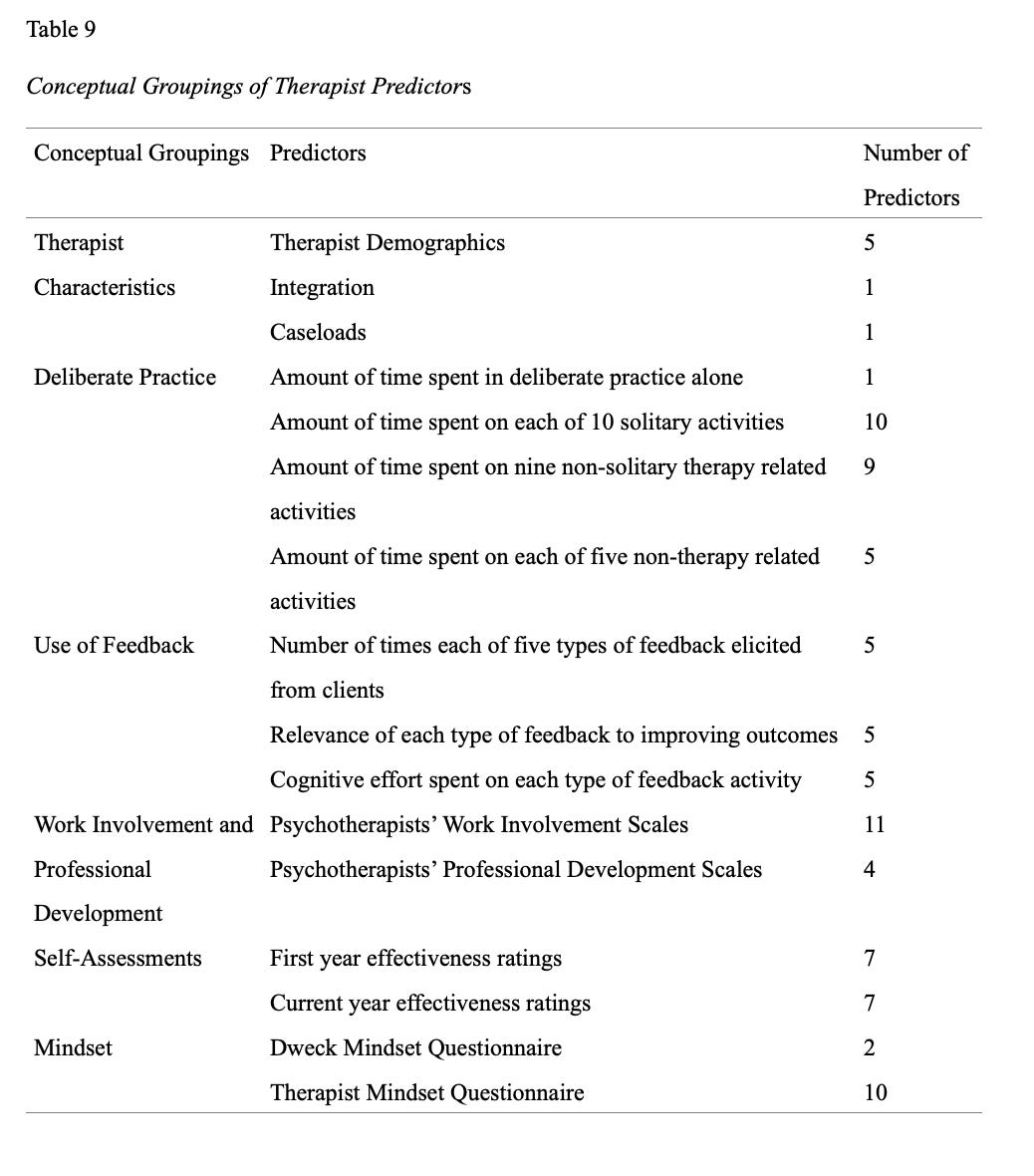

To give you a sense of the breath of the investigation, here’s an overview:

Based on Table 12, “There were no significant correlations of therapists’ adjusted client outcomes and the 25 relevance ratings of the taxonomy of domain related activities.”

Sorry, no silver bullet.

However, there were other factors worth considering, that are based on significant and nil findings.

Interesting Positive, Negative and Nil Findings

Significant findings and nil findings are just as important.

Nick Axford and colleagues wrote a paper called, Promoting Learning from Null or Negative Results in Prevention Science Trials.

…it would be remiss if, as a field, we did not reflect on how to learn from well-conducted null and negative effect trials, particularly because how we respond affects not just what happens after a trial but how we think about and design interventions and tests of interventions.

Here are the other factors that we examined in the Supershrinks study:

If you look into the Supershrinks study, amongst the significant findings, there were also other nil findings that are just as important.

Here’s five of them.

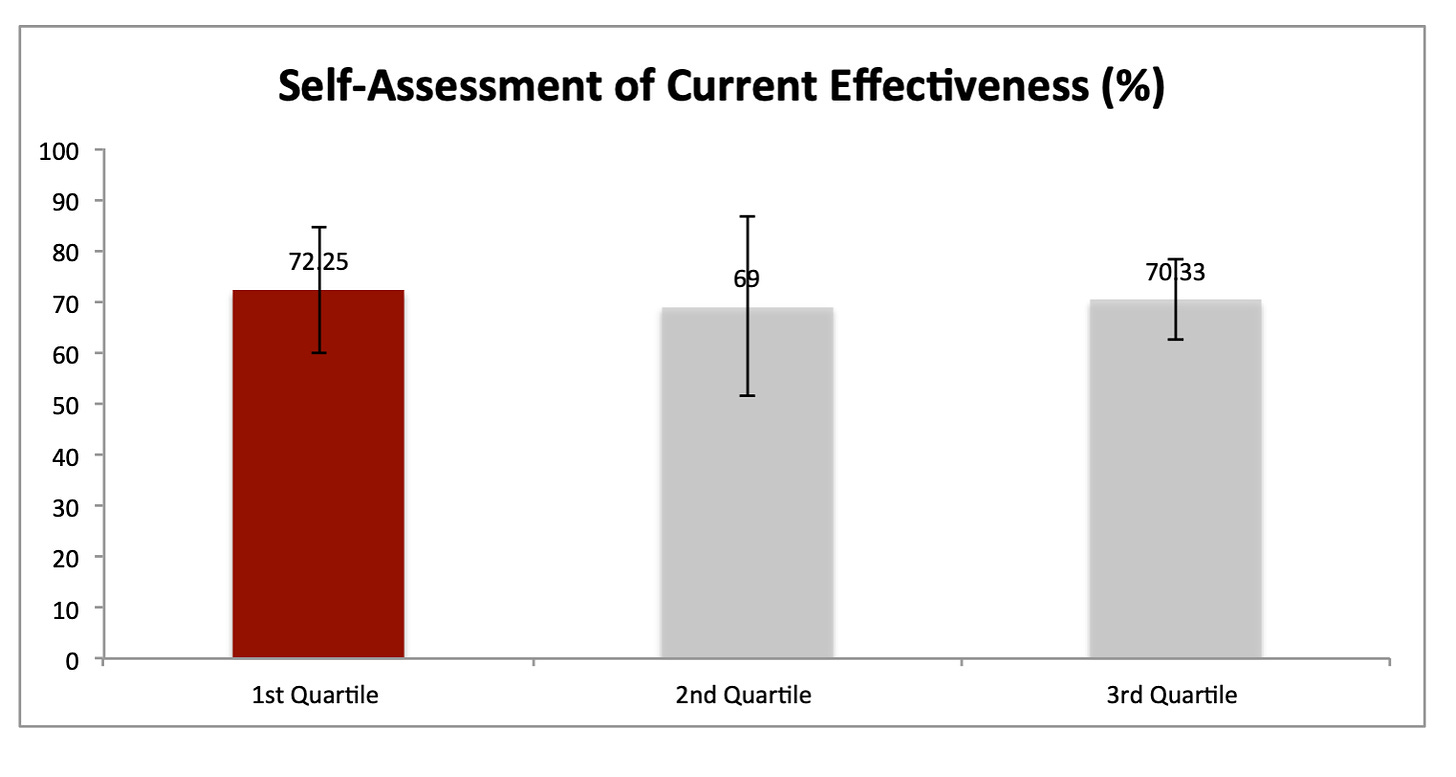

1. Self-Assessment

Even though the cohort of therapists that were participating in the study were engaged in monitoring their outcomes (CORE-OM), their self-assessment of their own effectiveness was not predictive of their outcomes.

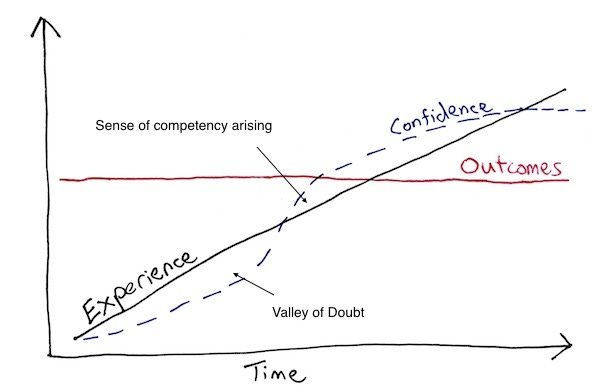

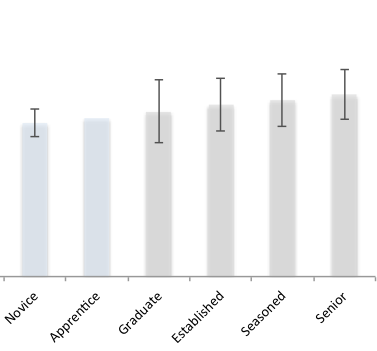

Look at this graph.

It seems like the highly effective therapists rated themselves someone more humbly, and the rest seemed to rate themselves roughly the same as the first quartile therapists. This somewhat coincided with Helene Nissen-Lie and colleagues studies on professional self-doubt, that PSD paradoxically predicted alliance positively4, and has a positive impact on patient’s interpersonal functioning.5

Doubt, it seems, can be a good servant, not a good master.

2. Healing Involvement

We turned our attention to another area that had been widely investigating. There was another group of researchers who have been studying the development of therapists across the globe.

In 1989, the Society for Psychotherapy Research (SPR) Collaborative Research Network (CRN) was initiated to study the development of therapists from various backgrounds, theoretical orientations, and nationalities (Orlinsky, Ambuhl et al., 1999).

In 2005, Orlinsky and Ronnestad (2005) published a comprehensive analysis of the way psychotherapists develop and function in their profession using the Development of Psychotherapist Common Core Questionnaire DPCCQ. This was based on nearly 5000 psychotherapists of all career levels, professions, and theoretical orientations in more than a dozen countries worldwide. Of interest, the authors found highly plausible convergence between the depiction of effective therapeutic process based on 50 years of process-outcome research (Lambert & Ogles, 2004; Orlinsky et al., 2004), and the broad dimension of therapeutic work experience, identified as Healing Involvement (HI) in the DPCCQ.

This book of mine is severely highlighted, scribbled and dog-eared.

Orlinsky and Ronnestad (2005) indicated that HI represented the therapist as the following:

Personally invested, (involved, committed) and Efficacious (effective, organized) in relational agency, as Affirming (accepting, friendly, warm) and Accommodating (permissive, receptive, nurturant) in relational manner, as currently Highly Skillful, as experiencing Flow states (stimulated, inspired) during therapy sessions, and as using Constructive Coping strategies when dealing with difficulties. (p. 63)

Orlinksy and Ronnestad found that HI gradually increased over time with experience.

Did this match up with being more effective?

The cohort that Orlinsky and Ronnestad didn’t have therapists who systematically tracked their client outcomes.

We did.

So we decided to test this. Given that we had longitudinal outcome data and therapists who completed the HI scale, we ran the numbers and we found it to be significant—in the opposite direction.

On average, therapists who rate themselves as more nurturing, invested, and affirming in the psychotherapeutic process than their counterparts are more likely to obtain poorer client outcomes.

3. Clinical Experience

Well, what about clinical experience?

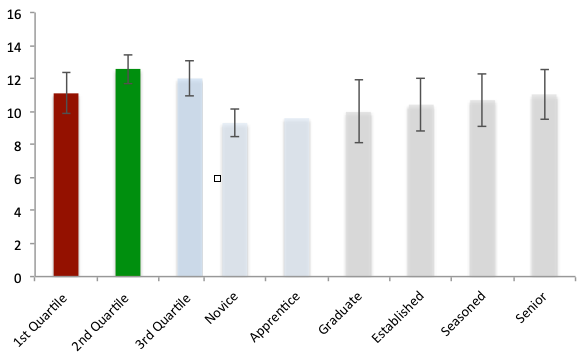

I think this graph says more than I can with words. The research plays out to be true in what we found as well as more recent studies.6

When someone says that they have 20 years of experience, what is really means is that they have 1 year of experience, repeated 19 more times.

4. Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

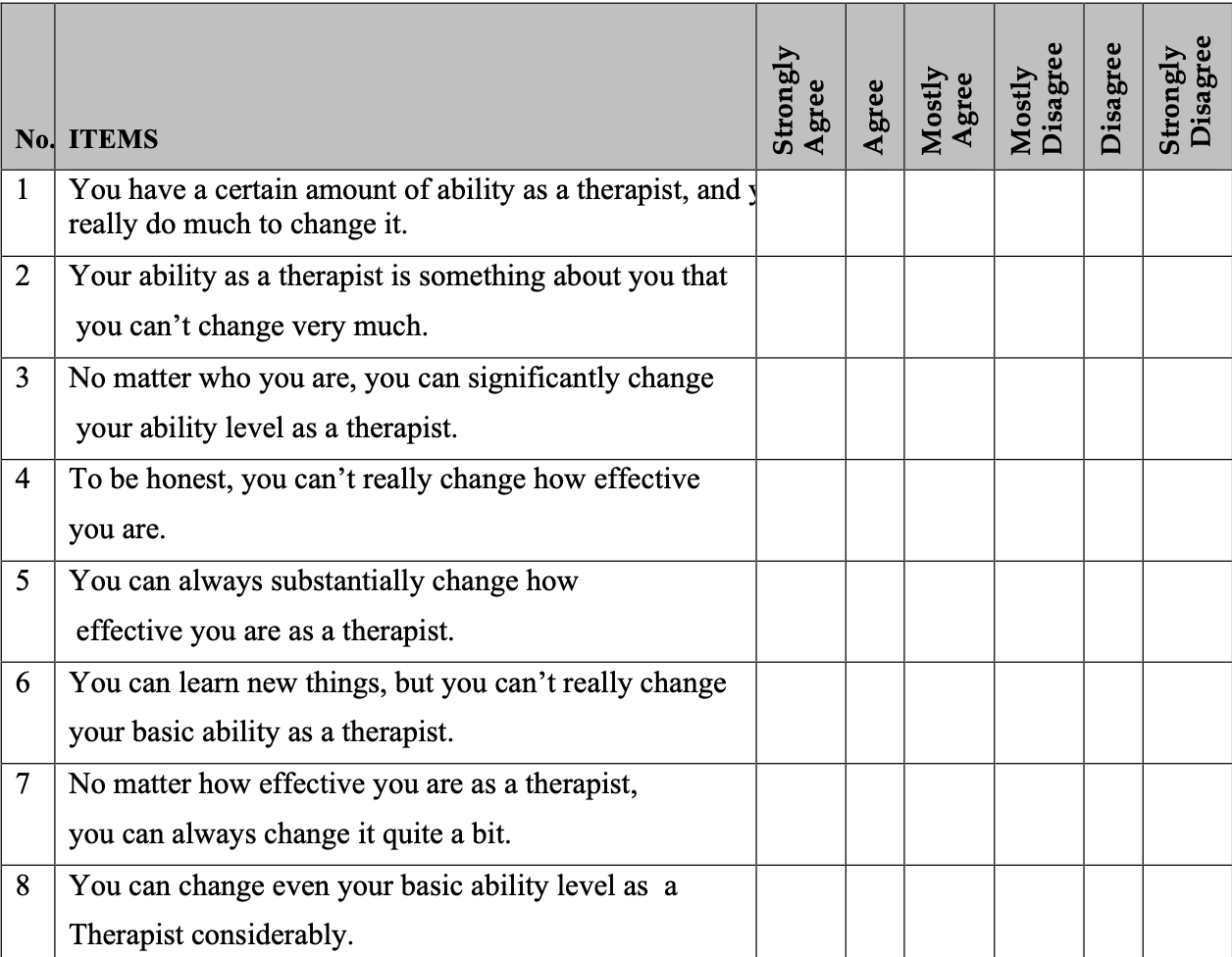

There has been a lot of talk about the importance of mindset, derived from Carol Dweck’s idea of implicit theories of intelligence. Every other podcast interview I hear someone mentioning this.

We tested this idea with our sample of therapists.

After some back and forth correspondence with Dweck, we embedded her measure in our battery of questionnaires and adapted the questions to suit therapists’ context.

Here’s how the adapted version looks like:

Given the existing evidence, we were hopeful to see some positive findings.

To our surprise, therapists mindset didn’t make a different. It failed to support our hypothesis.

Upon closer inspection, all but one therapist indicated self-endorsing to a growth mindset.

On hindsight, I would be hard-pressed to find a therapist who doesn’t believe in that change is possible. I doubt the mindset questionnaire was able to discriminate between therapists—or maybe a larger sample might? Who knows…

Given what we have seen in the Self-Assessment and Healing Involvement sections, it’s possible to hazard a guess that practitioners’ own beliefs about their work practice, and implicit theories about their own abilities, are not predictive of actual performance.

RELATED:

5. Surprised by Feedback

Finally, one unexpected finding.

We wanted to know how therapist elicit and take feedback. We asked, in the last typical work-week, how many times were you “surprised by client’s feedback about the session?”

This turned out to be a significant finding, albeit small. That is, higher performing therapists were more likely to be surprised by the feedback that they received from their clients.

It is possible to infer that therapists’ willingness to receive a variety of feedback, while conveying a sense of openness in therapeutic interactions with clients, may positively impact on client outcomes. While the therapist uses his or her expertise in creating a facilitative environment for the client, the therapist adopts a responsive and tentative posture, while conveying a sense of openness and newness towards the client’s unfolding narrative.

Side-Note: “Surprised by clients’ feedback” was negatively correlated to therapists’ self-ratings of Healing Involvement (HI; see above). This was also and not correlated to “DP alone,” suggesting that “surprised” and “DP alone” constructs are potentially measuring distinct facets of the therapists’ professional qualities and work practices.

Validity of the Measure

One last thing to address before we wrap.

Guided by everything we have learned from other domains in the studies of expertise and expert performance, we created quite an arsenal of questions. It’s long. It’s called RAPID-D, Retrospective Analysis of Psychotherapists’ Involvement in Deliberate Practice.7

To be clear, we have never thought of the RAPID-D like some kind of psychometric assessment tool. We have not insisted that the RAPID questionnaire was a “valid measure” of DP. Once again, given that we are at an early stage of understanding DP in psychotherapy, the battery of questions designed was meant to be exploratory, due to the nature of initial investigations.

Personal Rumination:

- What really matters:

I don’t really care about the concept of “deliberate practice” per se.

What I really care about is that we start to invest in things that can really make a real difference for the people we seek our help, and less about whether what we are doing is considered “DP” or not.

I sometimes feel like an uptight Asian in his mid-life getting upset watching therapists spent hundreds or thousands of dollars of their hard-earned cash on training that doesn’t ultimately move the needle on their clinical work. (But maybe as an Asian, I should be content that at least they get a certificate).

DP is not about us. It’s about others. - Concerns:

I worry we are going in circles. I worry we are not rethinking or reimagining our efforts to improve in a deep and meaningful way. I worry we are creating parallel problems to the “therapy model wars” as we had in the last few of decades.

(I am delivering a talk in a few months tentatively called “Seven Unpopular Ideas about DP.” I’m hoping the organisers allow me to record it for you.) - Take us forward:

Since the publication of the study, I had I really hoped for replication studies. Back then, the topic of the “Replication Crisis” was unfolding.

Some things might hold up; others not. And that’s ok. Granted, we could be wrong about the working definition of DP (see the 4 Pillars above and the two studies in footnotes #3). But hey, that is the process of science.

I’ve received several emails from people wanting to conduct replication studies or at least studies based on this.

As far as I know, only one replication has been published by Pauline Hanse and colleagues in 2023. It’s a great paper; you should check it out. Both studies had some similar findings that none of the activities related to therapist effectiveness. Plus, similar to the original study, therapist variables, “specifically their gender, years of experience as a therapist, and caseload also did not predict clients’ outcomes.”

The only pity is that their sample had strangely little differences between therapists8 (i.e., therapist effects of 1.5%) compared not only to our sample (5.1%), but to majority of other studies (therapist effects approx. 5-9%).

If we don’t see therapists difference play out, it’s harder to find further differences teased out. To their credit, they have a bigger sample (ours shrunk from 69 therapists in Study I to 17 in Study II).

In any case, since the study in question, we have conducted another study taking step further, taking DP into action. Once the publishers have put up the advanced copy, I will share it with you. It’s going to be OPEN ACCESS! Yay. I mean, we paid USD$3000 for it to be accessible to all. It’s a bizarre business arrangement to be honest.

So stay tuned!

Thank you for spending the time to read this. Wishing you well from the land down under.9

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments