Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 3 May. 2024

“Every impactful person brings to you themselves and not needing to proof

‘how impactful I am’, ‘how smart I am’, and ‘how needed I am.’”

~ Sr Joan Chittister.

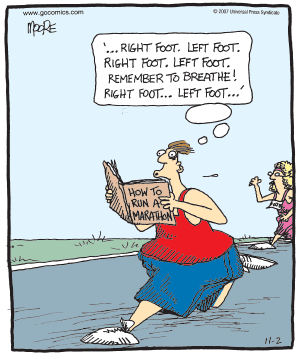

When we are trying to get better through deliberate practice, we have a tendency to hyper-focus on ourselves and end up tripping on our own foot.

That’s because we are trying to “perform.” When we are too focused on the outcome, we trade-off being open and flexible, so as to really engage in the ebb and flow, of the moment-by-moment unfoldings.

In other words, there is a paradox here. When you try to be impactful, you are less likely to be.

Little Deaths

Out of the three things Sr Joan Chittister mentioned, even though my aim is to create impact, I notice within myself a desire to be “impactful” and “smart.”

Now that I am putting this down, this realisation seems rather absurd. Yet, in moments of conversation in therapy, I hear myself conjuring up “strategic” moments to give a highly intelligence idea that might cause an impact. In others words, I’m tending more to my own thoughts than to the person. I was not speaking in order to listen, I was listening in order to speak.

Over time, I’ve come to begrudgingly appreciate what’s required in those moments is a sort of little death inside of me—that is, to let that go. These micro-grieves, seem to ask of me to make room for what is possible to come alive between us.

If we can let go of the ego, there is a chance for the session to come alive.

But there is a sort of inner-resistance to experiencing these little deaths within. I see this play out in the therapy room; I see this play out in parenting. In fact, this surfaces in most forms of meaningful long-term relationship engagement.

We are in an apprenticeship with grief. If we avoid it, we don’t know how to really live. Grief informs love, and love can only truly exist with grief around the corner, asking us to come to our senses.

Where Does This Come From?

As I look back in my early years, growing up in Singapore and the education system that I was in, for the most part, I felt stupid.

As I told my experience in this podcast episode, because of the ongoing pressure to perform, I wasn’t learning. I was “trying” to perform.https://open.spotify.com/embed/episode/400l4JRlcxHEWq9HS9A4jF

My saving grace was music. Forming a band at around 14-15 years old, I was opened up to a whole new world of possibilities. For the first time, learning took place at this speed of light.

Failing vs. Failure

Back to the therapy room, for at least the first 8 to 10 years in the profession, my core buttons get pushed whenever I feel like I’m not impactful or worse, sounding like I don’t understand i.e., stupid. The ghosts of “I am inadequate,” “I’m useless,” lurked under the hood.

Part of my personal journey is to make clear when it’s something to do with me and when it’s not. Whether or not if it was due to me, I have to find a way to create a healing space.

Plus, I had to learn to distinguish between failing and failure.

I worked with a family some time ago.1 The son was refusing to go to school. Given my background as a youth worker before I became a psychologist, I didn’t normally have big difficulties working with youths. But in this instance, I was rendered useless. I couldn’t engage with this particular 15 yr old. No matter how hard I tried, he didn’t want to talk. He was like a clamped sea-shell with a baseball cap. His response was often a shoulder-shrug.

Speaking conjointly with the parents was as far as we got. When we reverted to one-on-one session, he reverted to his default position. Maybe he clamped up even further.

My supervisor said to me to release the pressure from needing him to speak. And I asked, “The pressure in him or in me?”

“Both.”

That was an important point. To not push him to speak, and to not pressure myself to sound smart and impactful.

Sweating in the next session, I said to him, “I know you don’t wanna talk. I just want you to know, that’s ok with me. I’m sorry for pressuring you to open up. In fact, you probably think this whole thing is a waste of time.”

He looked up, and gave a wry smile. He said, “Look, it’s got nothing to do with you ok.”

It seems that after two decades in this profession that I am inching close to not taking things personally. This clarity of mind has afforded me the clarity to see in relations what was happening for the other person in front of me.

If I was too self-absorbed with my failure, I would have missed the person in front of me—what he was feeling, all those spokens and unspokens.

And yet, we were going nowhere. He agreed. I added, “I can see that you are hurting, and I can’t reach you. I’m sorry.”

“It’s alright,” his eyes gazed back to the floor.

“Would you like me to refer you to one of colleagues to give this another go?”

“No… it’s not you…”

“Yeah,” I interrupted, knowing that he had already said that earlier. “I can see that school environment is overwhleming, and you wished you can tolerate the mayhem going on there, but the truth is, you can’t focus or ignore it. You wish you could. Meanwhile, please don’t think that it’s something wrong with you… high school can be a pain in the butt. And it’s not permanent. We will find a way to cross this bridge.”

Next, dread came over me as I needed to tell the parents that I was not able to help their son. They were understanding. We discussed with his parents on making plans on various education options with the school. Meanwhile, I said to the family that I’d keep my doors open to them in the future if need be. We closed the session.

Some weeks later, with some trepidation, they took the homeschooling option. After high school, he worked his way into a design course in university.

Graceful Self-Forgetting

The late poet and writer John O’Donohue notes,

“Love begins with paying attention to others, with an act of gracious self-forgetting. This is the condition in which we grow.”2

Our therapeutic role is to be fully present, to be fully ourself, and then to leave oneself—a kind of graceful self-forgetting—so that we can truly enter into the improvisational nature of conversation.

Graceful self-forgetting means to let go of my expectations no matter how well-intentioned they might seem, to do what I can as an act of love, and not to be defined by the outcome.

It also means that I lose self-consciousness of myself and focus on the person right in front of me.

The paradox of our personal and professional development is to take the journey from self-examination to worrying less about how smart I sound, how impressive I am, and even how impactful I am.

To leave oneself, is required in order for us to be to fully engaged in conversation nature of therapeutic emergent reality.

Turn off the self-view. Remove the mirrors. Shine the light where it needs to be.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments