Note: This article was originally published in Substack on 22 Sept. 2023

Could less information actually be better in our improving our clinical decision-making process?

Turns out that with more information, our confidence might increase, but not the quality of our decisions.

Consider the following scenario posed by Gerg Gigerenzer and Stephanie Kurzenhaduser.

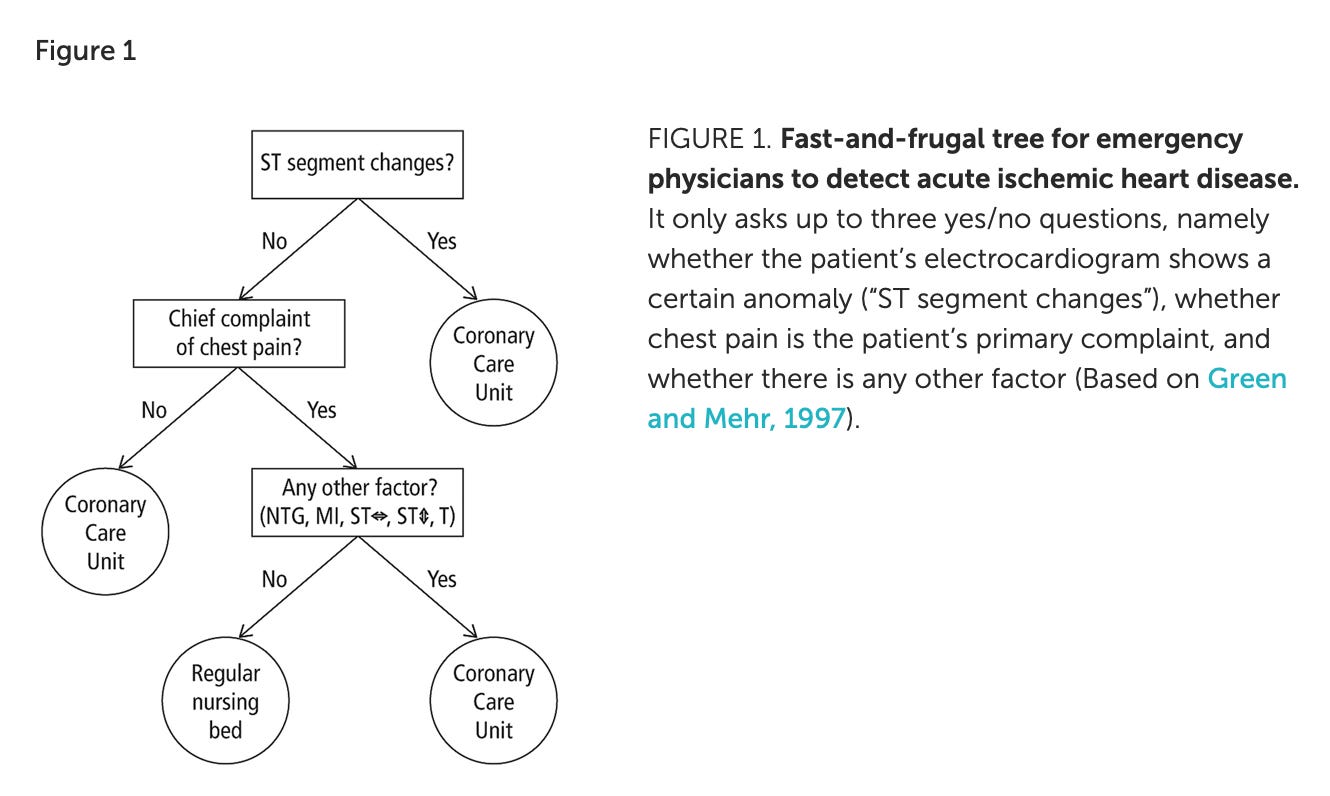

A man is rushed to the hospital with serious chest pains. The doctors suspect acute ischemic heart disease and need to make a decision, and they need to make it quickly: Should the patient be assigned to the coronary care unit or to a regular nursing bed for monitoring? The decision to admit a patient to a coronary care unit has serious medical and financial consequences. How do doctors make such decisions, and how should they?

There are 3 broad approaches doctors can approach these challenging treatment decisions.

-

- Rely on experience and intuition

-

- Statistical probability calculations, or

-

- A fast and frugal heuristic.

When doctors rely on their intuition i.e., #1, they sent 90% of patients to the coronary care unit. Why? Physicians fear malpractice suits. “If they do not send a patient into the care unit, and he subsequently has a heart attack, but less so if they send a patient into the unit unnecessarily, and he dies of an infection.” This defensive decision making incurs unnecessary costs, decreases the quality of care, and adds to additional risks of secondary infections to patients who should not be in the unit. More, “Only 25 percent of the patients admitted to the coronary care unit did actually have a myocardial infarction.”

Okay. What about a more robust and thorough approach, like a statistical probability calculation using logistic regression analysis i.e., #2?

Researchers at the University of Michigan Hospital trained physicians to do just that. Physicians were trained to use the Heart Disease Predictive Instrument (HDPI), which consists of a chart of 50 probabilities, with the absences or presence of combinations of seven symptoms…and insert the relevant probabilities into a pocket calculator (yes, this was the 1990’s), which spits out the probability that a given patient has acute heart disease.

Nevermind the hassle of a mathematical computation. It’s pretty thorough, isn’t it?

Before we look at the results, let’s contrast the third approach in decision making, a fast and frugal heuristic i.e., #3.

Roughly speaking, a fast and frugal heuristic is

1. Not a set of strict formula, but a guide

2. Meant to be designed beforehand, and not reactively

3. Deployed in an uncertain environment, as part of an “adaptive toolkit.”

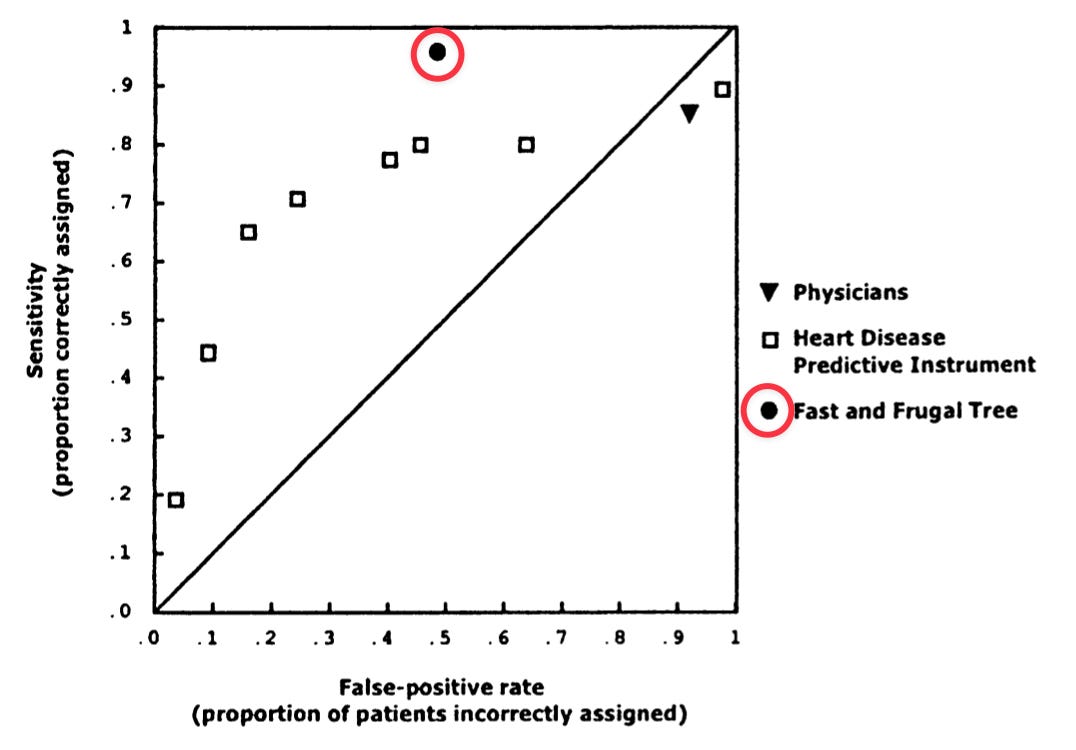

Now, let’s look at the results. How effective is a fast and frugal heuristic compared to our intuition, as well as a more thorough statistical analysis?

Turns out that, in an uncertain world, according to Gerd Gigerenzer, you can do actually make better decisions with less information.

Applying the Fast and Frugal Heuristic to Psychotherapy

How does the fast and frugal heuristic apply to the practice of psychotherapy?

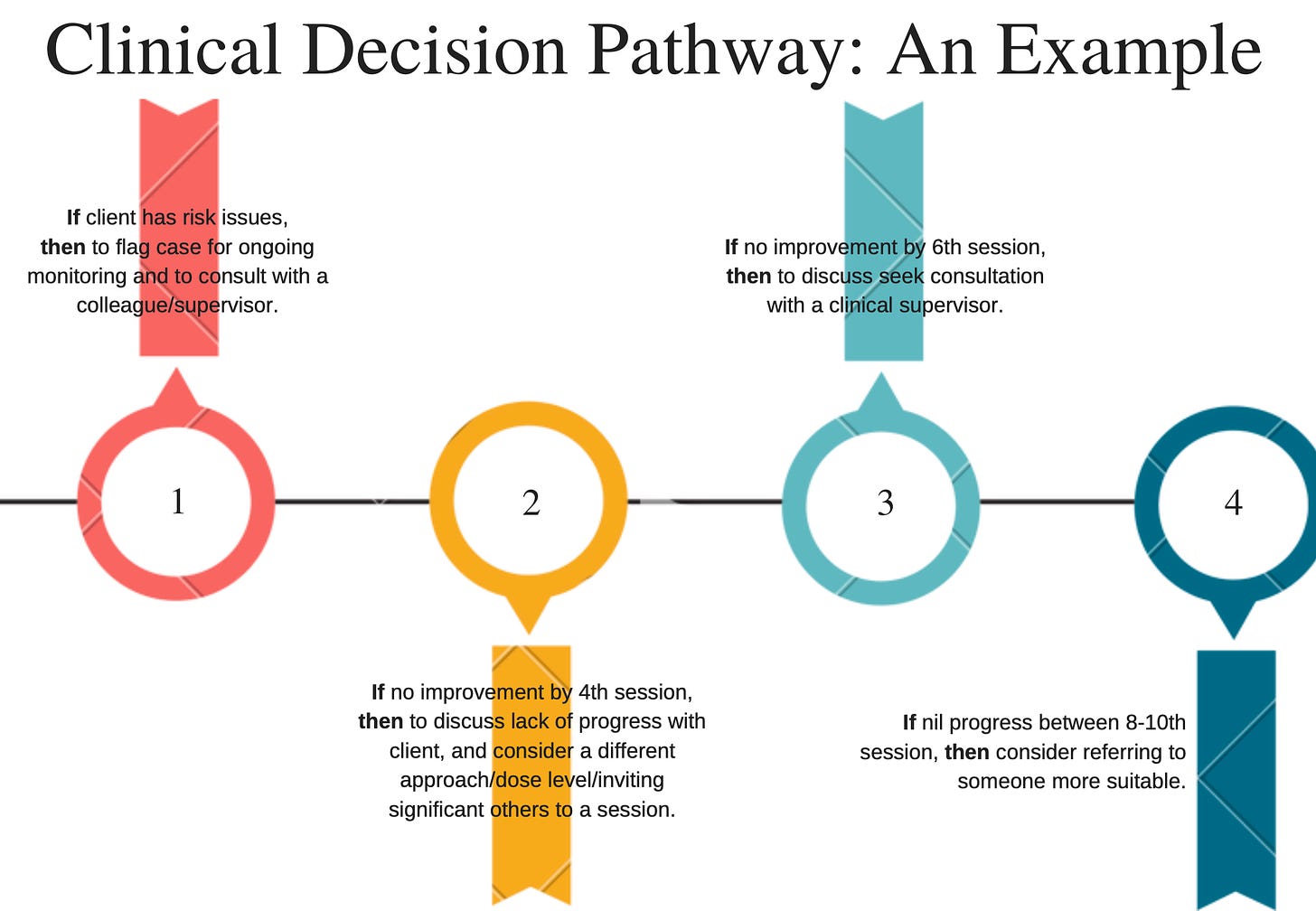

In order to improve the odds of success for a given client, we need to develop a clinical decision tree to aid decision-making based on a client’s level of progress and engagement levels across the progress of sessions.

This is not something you create reactively, but it’s something that you can–and should–design beforehand.

Imagine you develop a handful of “checkpoints” in the process of therapy to improve the odds of success for your clients. What sort of information would you fill it in with to guide your decision-making?

Based on the cumulative evidence of what we know about the factors influencing outcome, the average number of sessions typically attended, as well as the odds of improvement if early progress isn’t experienced, here’s a potential fast and frugal clinical decision pathway.

In the course Reigniting Clinical Supervision (RCS), we go into the weeds of how clinical supervisors can help their supervisees map this out.

This clinical decision pathway is not meant to be employed as a rigid rule, but as a guide. It’s like a basecamp pitstop at different checkpoints. If left purely to our reactive intuition, we might be prone to an optimistic bias and fail to take heed of key signals i.e., client not experiencing gains for more than 10 sessions and the alliance measures have not increased over time.

Take a look inside this particular module in RCS for more details:

Not Ignorance

This begs the question, why does more information doesn’t necessarily lead to better decision-making?

There are two possible explanations.

First, author and surgeon Atul Gawande makes an important point about the distinction between ignorance and ineptitude.

Here’s what Gawande means by ineptitude:

…the knowledge exists but an individual or group of individuals fails to apply that knowledge correctly. What’s really interesting to me about living in our time and in our generation is that that is a remarkable change of living now: that ineptitude is as much or a bigger force in our lives than ignorance.

Elsewhere, Gawande says,

Our great struggle in medicine these days is not just with ignorance and uncertainty. It’s also with complexity: how much you have to make sure you have in your head and think about. There are a thousand ways things can go wrong.

Here’s a second explanation: Dilution.

Consider this example. How much would you pay for a 24 piece dinnerware set consisting of the following:

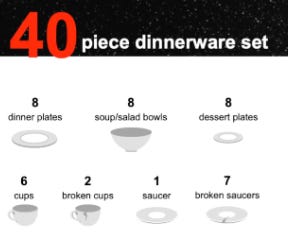

Now consider how much would you pay for a 40 piece dinnerware set consisting of the following:

Turns out that on average, participants are willing to pay £390 for the 24 piece dinnerware set, which consists of 8 dinner plates, 8 soup and salad bowls and 8 dessert plates all in good condition.

On the other hand, participants are willing to pay £192 for the 40 piece dinnerware set, which consists of 8 dinner plates, 8 soup and salad bowls and 8 dessert plates all in good condition, as well as 8 cups (2 broken), 8 sauces (7 broken).

Why would we pay more for less? Rationally speaking, the 40-piece dinnerware set includes all elements you would get in the 24-piece set, plus six cups and one saucer.

This is the Dilution effect.

Niro Sivanathan points out that when we’re processing information, our minds utilise 2 categories of information: diagnostic and nondiagnostic.

Diagnostic information is information of relevance to the valuation that is being made.

Nondiagnostic is information that is irrelevant or inconsequential to that valuation.

And when both categories of information are mixed, dilution occurs.

Watch this TED talk by Niro Sivanathan:

Niro Sivanathan: The counterintuitive way to be more persuasive | TED

No Description

In other words, when we take a grab-bag of information without parsing out what is actually predictive of improvement in therapy, we are likely to inflat our confidence in the decision-making process, and paradoxically, dilute what is actually important in influencing outcomes.

On a related note, as I’ve wrote about in the book, The First Kiss: Undoing the Intake Model… if we don’t factor in what is relevant vs non-relevant information, we are at risk of gathering “True but Useless” (TBU) information.

See this related post: Is Less Really More?

Before we wrap up, take another look at the Clinical Decision Pathway example illustrated above. You will notice that there are only 3 vital pieces of information:

-

- Risk issues,

-

- Client outcomes across sessions, and

-

- Level of engagement across sessions.

I’m sure there are other multi-factors that could be optimised and accounted for (i.e., complexity, severity, chronicity). But adding more information might not necessarily improve our decision-making; neither is too little information. That sweetspot is perhaps what Herbert Simon calls “Satisficing,”

In summary, if you are clinical supervisor, this is one thing you can do to help your supervisees to have in place: Develop a fast and frugal heuristic to guide them in their decision-making, so as to improve the odds of success with their clients.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments