Note: This article was originally published in Substack released on 1 Sep. 2023

People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.

~ Coach John Wooden, from You Haven’t Taught Until They Have Learned, p.9

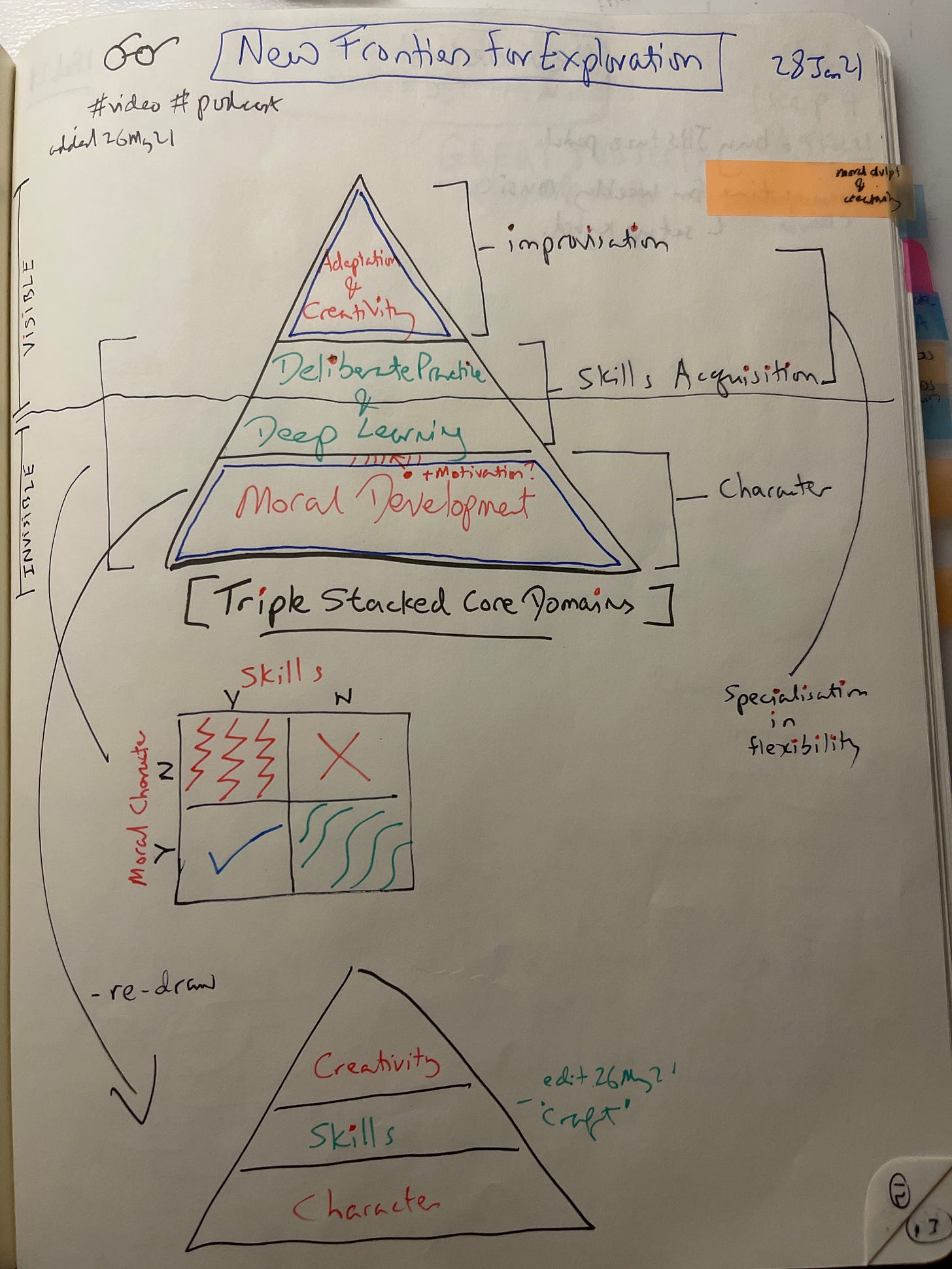

I’ve been chiseling at this for far too long. Since late January 2021, I’ve been trying to figure out a way to articulate what I’m about to describe in today’s post.

I think there is some further shaping to do, but I would like to share this with you on Substack, before it goes into the archives in Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD) blog sphere.

If you have reactions or suggestions, I would love to hear from you in the comments below.

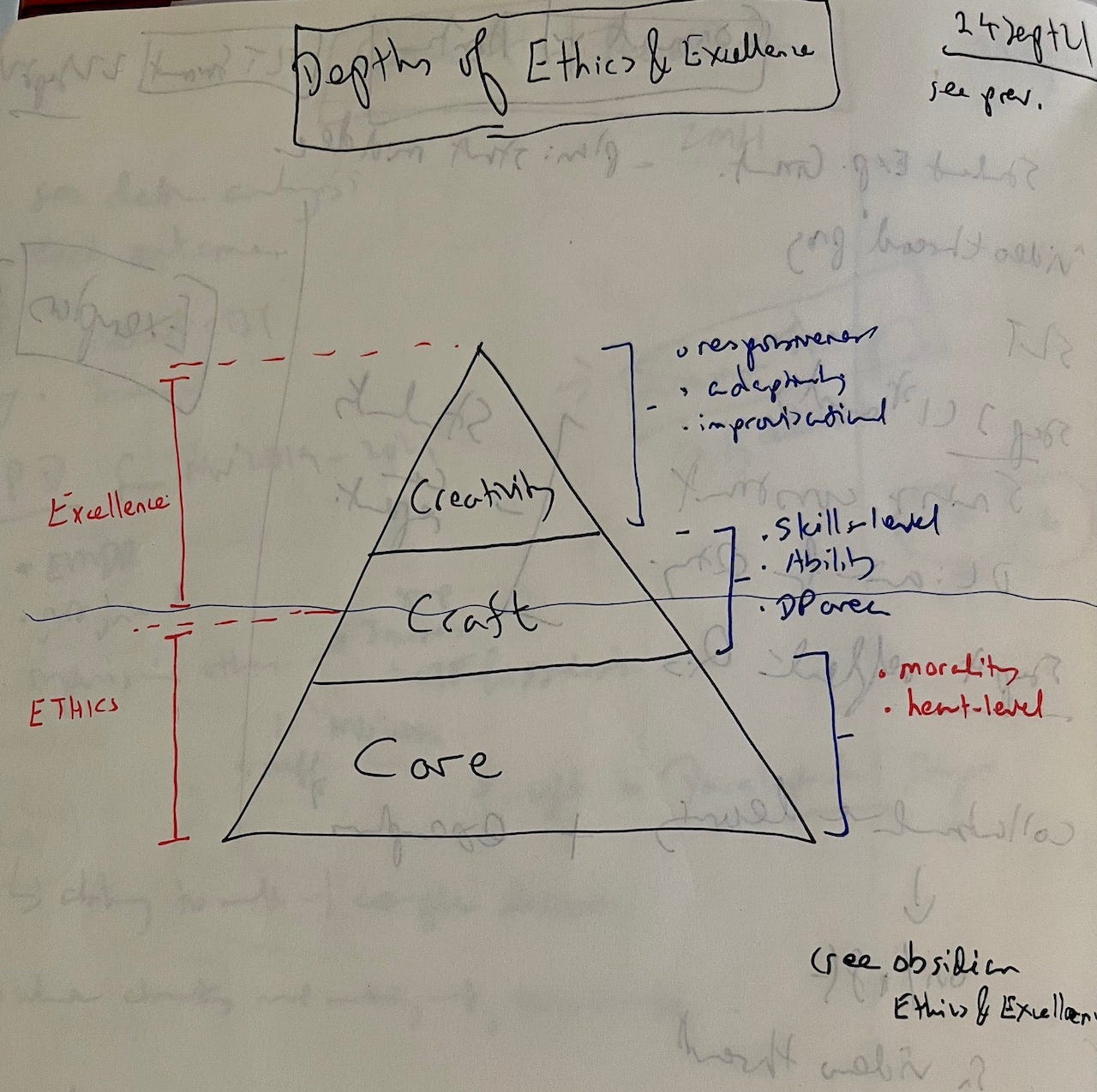

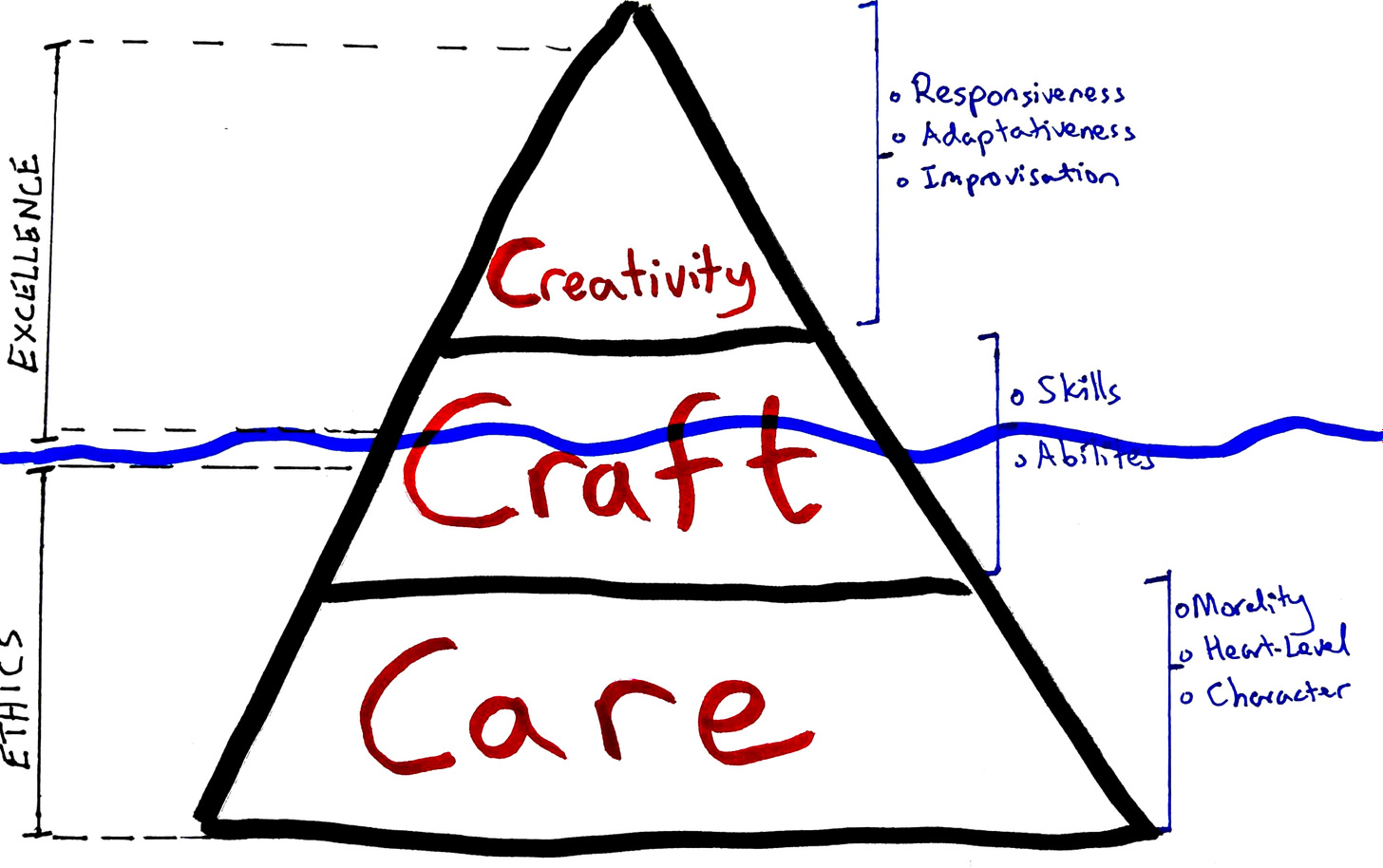

What I’m going to try to describe are 3 levels of thinking about the topic of excellence and ethics, or performance character and moral character.

The 3 Layers

Here’s an overview of what I’ve been thinking about: Craft, Care, Creativity.

Let’s start with the centerpiece of the iceberg: Craft.

I. Craft

Much of our efforts have been focused in this domain of craft.

Craft is about the development of expertise.

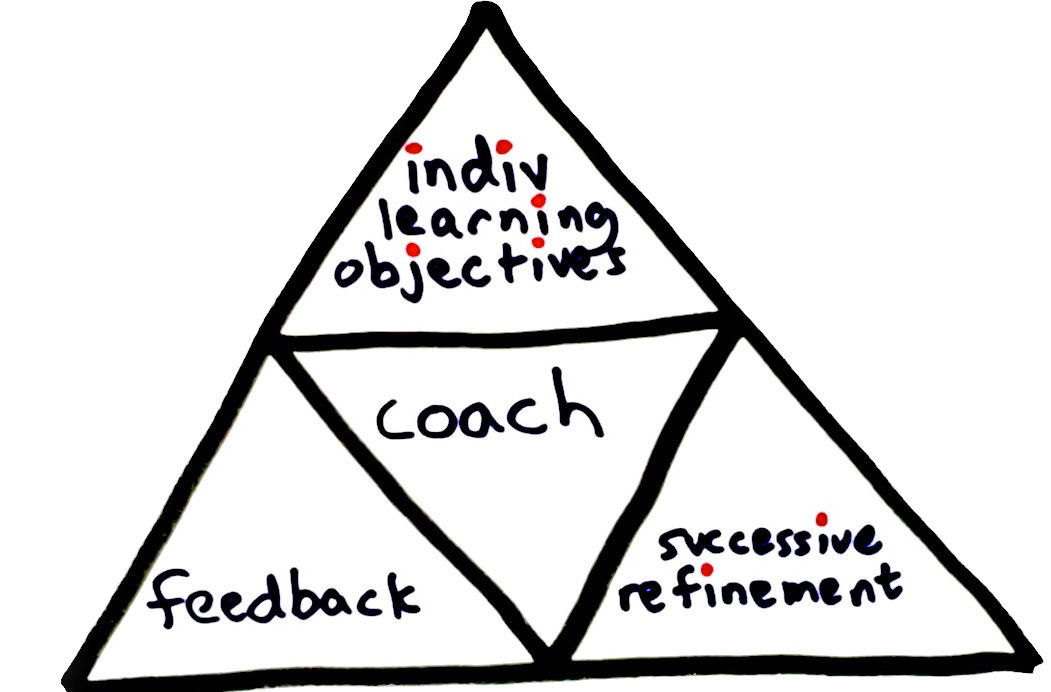

In our striving to do better and be of better help to our clients, we embark on ways to improve our skills and abilities. We engage in deliberate practice in order to hone in on our craft as relational beings, figuring ways to move the needle in achieving better outcomes, one client at a time, one therapist at a time. (For more on what deliberate practice looks like, see this post)

As we have described elsewhere, Deliberate practice is not just mere repetition, but it is guided by

- Figuring out where you are (i.e., baseline performance),

- Where you need to grow (i.e., your zone of proximal development),

- A system of deep and personalised learning, and

- Within an environment of feedback.

II. Care

Besides Craft, there is another dimension that we often take for granted.

A distinct and interdependent factor to consider besides performance character is moral character.

What is character? In the book Leading with Character, Jim Loehr says,

The word “character” comes from the Greek word, “kharakter,” a chisel or marking instrument for stone or metal.

In a sense, we chisel our true essence from the bedrock of life, one moral decision at a time.

Think about this. In our psychotherapeutic work with each person that shows up in our office, the defining mark is how we treat others.

Am I patient, or am I hurried?

Am I listening in order to speak, or am I speaking in order to listen?

Am I opening myself to the explorative possible with this person, or am I going in with a fixed agenda?

Am I relating with this person with dignity, or am I becoming transactional?

In a sense, this second component of Care is hidden in plain sight. It is our hidden scorecard. There is no quantified outcome measure of success in this domain.

On the one hand, expertise is often associated with technical knowledge and skill, which can be used to achieve specific goals or outcomes. On the other hand, morality is concerned with questions of right and wrong, and the ethical implications of our actions and decisions.

Samuel and John Philips provides their definition of character, one that meets both mind and morals:

Goodness without knowledge is weak and feeble, yet knowledge without goodness is dangerous. Both united form the noblest character.

Expertise can be used for both good and bad purposes, depending on the moral character of the expert. For example, a skilled surgeon might use their expertise to save lives, but they could also use it to harm others if they lacked a strong moral compass. Similarly, a financial expert could use their knowledge to help people make wise investments, but they could also use it to exploit others for personal gains.

Thankfully, most therapists I know are in this profession because of deep care and regard for others. Many have also experienced being in the receiving end of such guidance. But this side needs to be returned to, again and again. Returning back to your unique “origin” story can serve as an anchor. Because in order to care for others, we must tend to our inner life, and remember in the first place, what brought me to want to be help to others in the first place?

Craft and Care are not mutually exclusive; we need to work on both. Craft manifests more externally, whereas Care is an interior condition.

One time, I kept count on how many times in one day at my clinical practice I had to exercise moral judgment. I quickly noted these down between sessions. There were at least 3 instances:

- A young client wasn’t keen to talk… there was a part of me that just wanted to let that be and not bother with trying a different tact. Thankfully, I kept at it. I later learned that something had happened to him at school earlier. So we went there.

- Another client had to change the session to a telehealth call. Since she couldn’t see me, I found myself tempted to check my email during the call.

- Third client had a last minute cancellation. Should I charge cancellation fee this time? But he’s struggling financially…

Only I know this about this hidden scorecard.

III. Creativity

Finally, let’s switch gear. A third domain exists right at the top of the ice-berg: Creativity.

I think of creativity as the following:

Creativity = Making connections + creating something novel and valuable.

Specifically, for the use of this word in the practice of psychotherapy, to be creative is to be

- Responsive,

- Adaptive, and

- Improvisational.

Ben Stiles and colleagues defined what it means to be responsive in the therapy room:

…behavior that is affected by emerging context, including emerging perceptions of others’ characteristics and behavior…involving bidirectional causation and feedback loops.

In suggesting that psychotherapy is responsive, we mean that the content and process emerge as treatment proceeds, rather than being planned completely in advance.

In other words, as we open ourselves to the interactional process, we can’t help but be altered, and we adapt and utilise what the client brings into the therapy room. Such a process is more akin to an improvisational jam session than a performance of a classical piece, pre-ordained on a musical sheet.

But wait. Could it be that some therapists somehow are more creatively flexible?

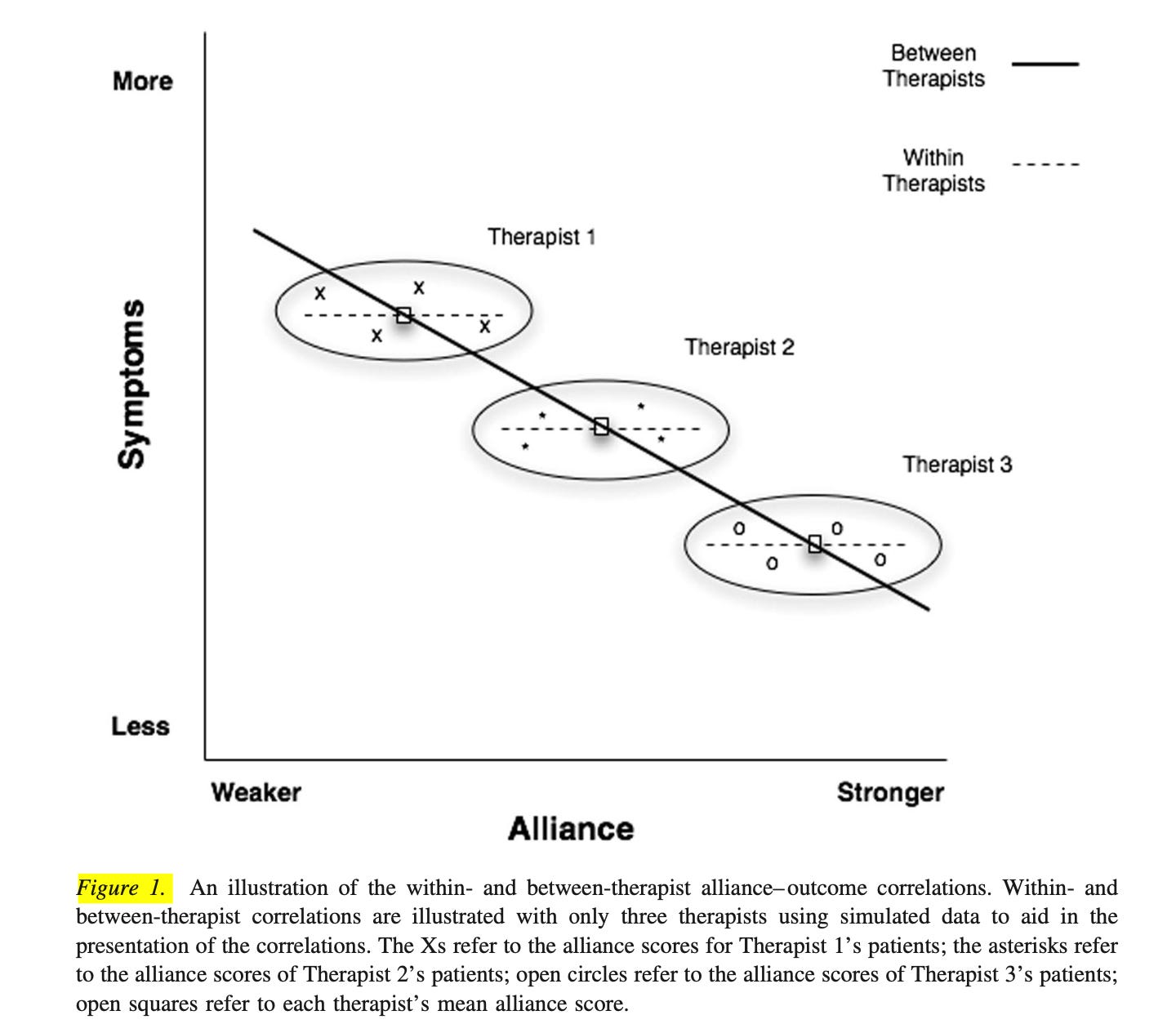

A seminal study by Baldwin and Wampold hints at a potential answer. This is their research question in plain English: Who is responsible for the alliance?

They tested to see if the alliance-outcome relationship was due to one of the following:

- Client (i.e., some clients are better at forming a collaborative relationship);

- Therapist (i.e., some therapists are better at forming a collaborative relationship);

- The interaction between client & therapist (i.e., it is the fit between two parties).

- Alliance happens as a consequence of good outcomes (i.e., this is a reverse of the alliance-outcome relationship, that is the change experienced in therapy led to better alliance formation).

Most people I quiz at workshops pick #3. The fit between client and therapist. What Baldwin and Wampold discovered was not what we intuitively would have guessed.

The alliance boiled down to differences between therapists, which accounted for a significant proportion of the alliance-outcome correlation (#2).

What’s more, the differences between therapists accounted for 97% of the variance in client-rated alliance (You’d rarely hear a single factor accounting for such a big proportion of the variance in social sciences).

Said simply, some therapists are flexibly better at working with a wide range of folks than others.

Finally, it’s worth stating that to be “improvisational” doesn’t mean “anything goes,” “just go with the flow,” or “winging it.”

Improvisation, originates from the Latin ‘improvisus’, meaning “not yet seen ahead of time.”

In discussion about music improvisation, Ted Gioia (incidentally, one of my favorite writers on Substack) says,

The improviser may be unable to look ahead at what he is going to play, but he can look behind at what he has just played, thus each new musical phrase can be shaped with relation to what has gone before. He creates his form retrospectively. ~ Gioia, 1988.

Or consider anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who had a significant influence on the evolution of family therapy:

The theorists can only build his theories about what the practitioner was doing yesterday. Tomorrow the practitioner will be doing something different because of these theories,”

In other words, it is after the fact that we develop a theory of our own. Before that, we improvise and learn.

I think of the disposition of improvisation as the following:

Improvisation = Openness and freedom to listen + Willingness to take risks – Expectations

Indeed, the practice of improvisation is paradoxical. If development of our Craft is develop expertise, the practice of Creativity is to be unpracticed. To suspend our existing knowledge and willing to apprentice ourselves to each person’s experience.

The enemy of improvisation is control. Instead, there is an active surrender to relational endeavor, whilst guiding the dynamic process based on the emergent conversation.

Excellence and Ethics

In looking at the 3 domains of Craft, Care, and Creativity, we can group them into two broad categories: Excellence and Ethics.

Here’s a list to contrast the differences:

Excellence

– Performance

– Driven

– Push for results

– Goal-oriented

Ethics

– Care for the other

– Deep listening

– Soften to relate

– Soul-oriented

In my estimation, Craft exists in-between Excellence and Ethics. Craft is to strive to do better, but it also has a dimension of not only being goal-oriented for skills acquisition, it also requires you to be soul-oriented and to give you undivided attention to the person in front of us.

Meanwhile, Creativity is perhaps our fullest expression of excellence. By being an active agent of connecting the dots, we are co-creating something vibrant and useful in service of the other.

Examples of Missing Pieces

Here are some hypothetical examples if some pieces of the iceberg are missing:

1. A therapist with Care, but no Craft and Creativity.

– This therapist is prone to feel helpless and impotent.

– Likely to become easily overwhelmed

– Prone to burnout.

2. A therapist with Craft, but no Care and Creativity.

– Most therapists would be ok in the short-term, but not sustainable in the long-term.

3. A therapist with Creativity and Care, but no Craft.

– Clients might experience this therapist as really caring by somewhat disorganised.

4. A therapist with Craft and Care, but no Creativity.

– Some clients might benefit from this therapist, but some might find this person rigid or inflexible.

6. A therapist with Craft and Creativity, but no Care.

– Refer clients elsewhere.

The Takeaway:

There is more to be said, especially around the domains of Care and Creativity. But for now, here are three takeaways:

- Each of the 3 domains needs our attention. I believe these can be cultivated.

- Emphasising solely on Craft is likely to be insufficient, and

- The morality of Care is hard to talk about, but I believe it deserves more of our attention—like brushing our teeth, we should be attending to this, twice daily. The continuous praxis for therapists is to make space, slow down, and learn to soften.

It’s not just about being guided by the ethics of fear (e.g., I better to do right thing and not get in trouble with the governing bodies), but by the morality doing what’s right for the common good.

In that process, we turn outward. We learn a form of graceful self-forgetting.

May the words of legendary basketball coach, John Wooden continue to reverberate:

People don’t care how much you know until they know how much you care.

If you would like to learn more topics that can help your professional development, subscribe to the Frontiers of Psychotherapist Development (FPD). On Frontiers Friday (FPD), we serve you directly to your Inbox highly curated recommendations each week.

Recent Comments