Note: This is a compilation of Frontier Friday, a weekly Substack published, originally released on 17 Mar. 2023

PART I

📕Must-Read: Premature Termination in Psychotherapy: Strategies for Engaging Clients and Improving Outcomes

This 2015 book by Joshua Swift and Roger Greenberg is one of the best resource on this specific topic. The researchers have drawn from a large body of work.

(Also, we are thrilled to have Joshua Swift contribute a chapter in our upcoming book, The Field Guide to Better Results.)

I recommend that you read the book. For now, here’s my summary.

Key Grafs:

(note: I’ve added some of my perspectives next to the key highlights from this book when it’s relevant. I’ve labeled them as ‘DC.’)

A. Occurrences:

– About 1 in 5 people terminate treatment prematurely.

– Specifically, “The average dropout rate across all studies was only 19.7%, with a 95% confidence interval of 18.7% to 20.7%.” (p. 171).

– University-based clinics, including psychology department training clinics and university counseling centers, experienced the highest average rates of premature discontinuation. This is likely due to younger clients, trainees providing the services, lack of investment and perceived credibility due to nil or minimal fees charged.

B. Strategies:

– Frequency expectation: The mere act of specifying duration was associated with lower dropout rates.

– Most people expect to attend only a few appointments, but if made aware that a greater number of sessions are involved, “they know what to expect and are more likely to follow through with that expectation.” (p. 49). (DC: Though I do not provide an exact number, I usually say to my clients that we’d meet for just a few sessions to see if this is helpful. Plus, I’d monitor their progress using outcomes measures session-by-session. If things aren’t going in the right direction, it’s my responsibility to tweak/adjust/calibrate in order to better help them. Finally, it’s my job to render myself out of a job.)

– Provide role induction: i. what to expect (process, treatment rationale), ii. role of therapist, and iii. role of client. (DC: As I’ve outlined in the Structure and Impact Course, I talk about the need to provide a scaffold based on figuring out“Where are we, where we are going, and why.”)

– (DC: Do not take for granted what client might expect from therapy. I recall a particular case where the client thought that therapy was supposed to “happen” to him, just like in the movies where he laid down on a couch while I analyse him behind his back.)

– Don’t forget to address logistical concerns. (DC: This could relate to issues with transportation, finances, caregiving responsibilities, etc. We can also use systems to help people with their logistics. For instance, in our group practice, we found that simply having an automated sms reminder 48hrs prior to their appointment dramatically reduced DNAs. The unintended consequence of this was that in some rare occasions, clients arrived at the right time, but one day earlier!).

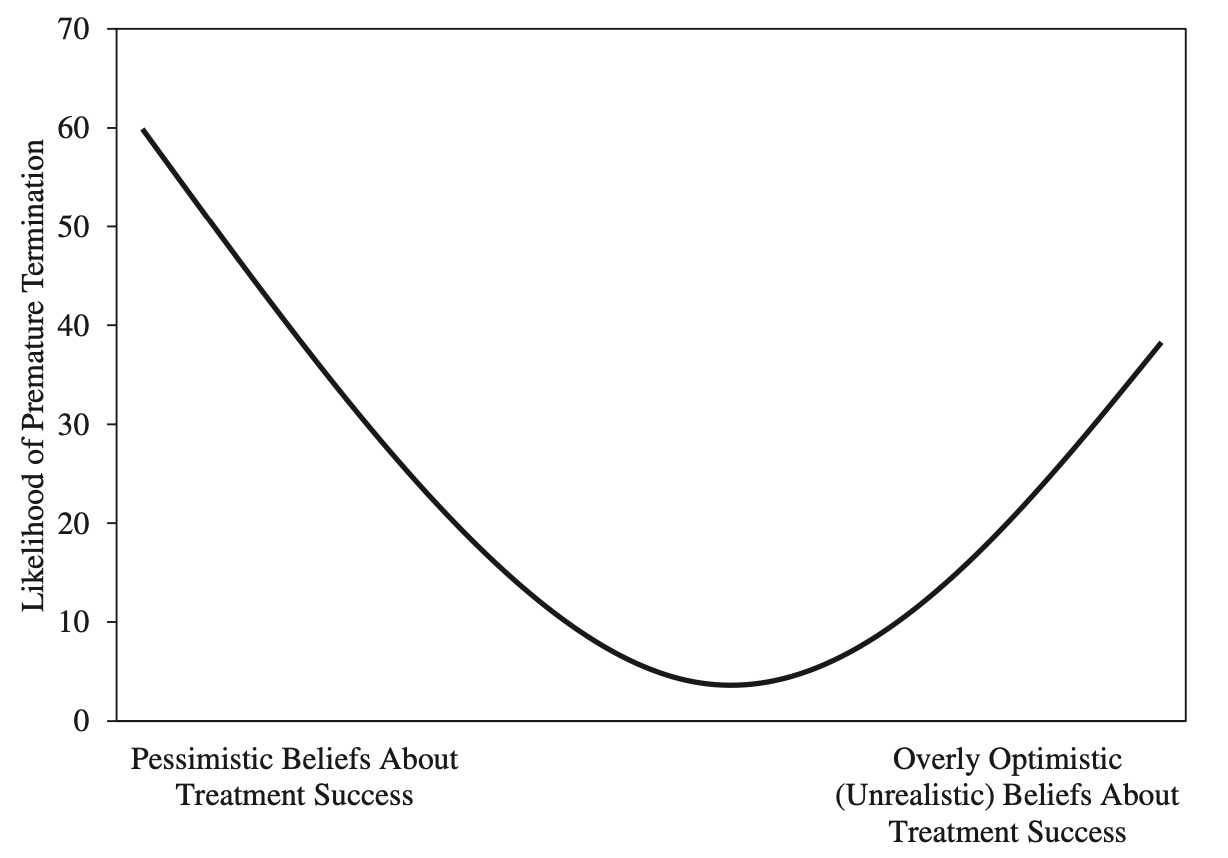

– The curvilinear relationship between outcome expectation and treatment dropout:

– “Not only is it important for clients to believe that the treatment will help, they should also believe in the effectiveness of their therapists.” (p. 119). (DC: This speaks to the importance of a therapists needing to do something that they themselves believe in).

– Distinction between client expectation and client preferences: “preferences represent desires and values, expectations reflect what clients actually believe should or will happen in therapy.” (p. 80). (DC: I would argue that it would do everyone good to match unique preferences at the pre-therapy phase, if there’s any. For instance, someone has a specific preferences of seeing a female, someone with a particular spiritual orientation, etc.)

– “…clients who receive their preferred conditions were between one half and one third less likely to drop out of therapy prematurely compared with clients who did not receive their preferred therapy conditions.” (p.85)

– Planned Termination can lead to lower rates of premature discontinuation. (p.98) (DC: I’ve observed this in our Supershrinks study as well. More effective therapists have a higher rate of planned endings. On a practical note, at the start or even pre-therapy phase, I would recommend enquiring about clients initial thoughts of expectations on treatment length).

– Address the fact that focus of therapy may change over time, thus treatment length might change.

– Address issues regarding a decline in hope or motivation.

– Therapists are poor judgers of recognising when their clients are getting worse.

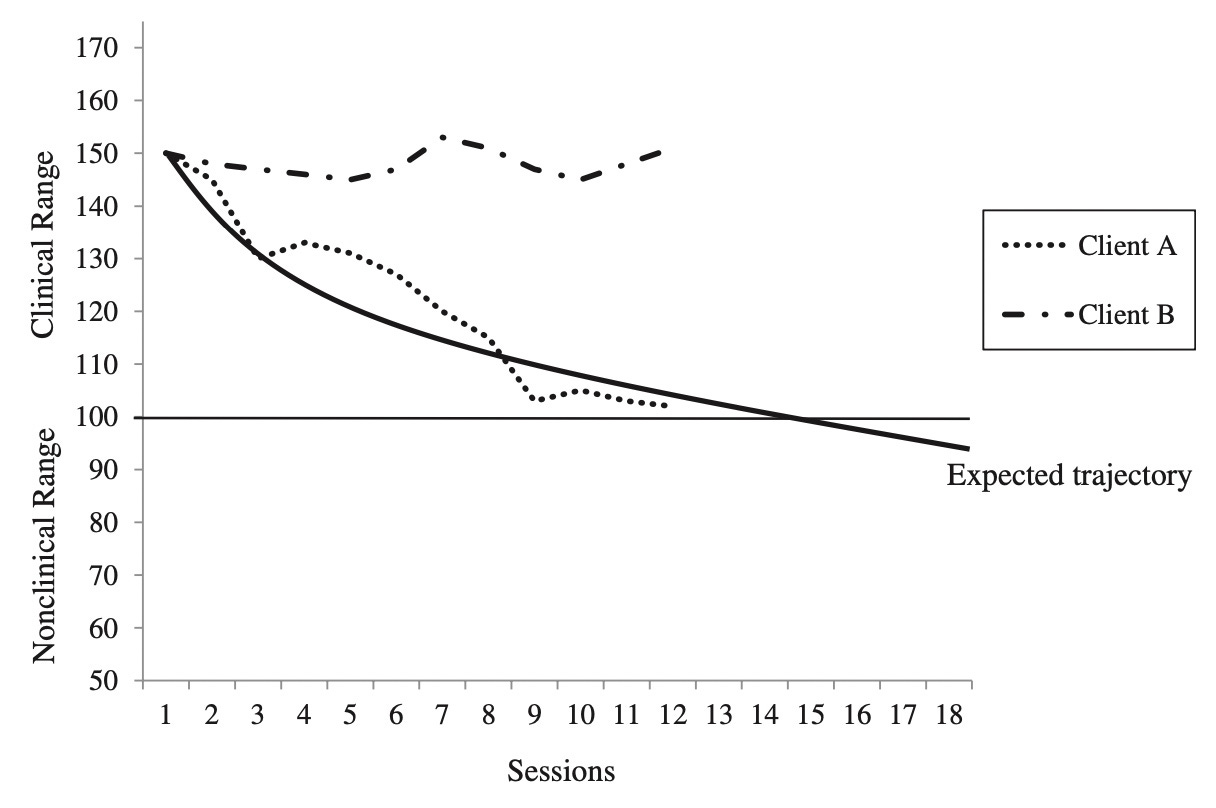

– Monitor progress systematically, because a client is more likely to dropout if it deviates from expected trajectory (see figure below).

Reflection: Contemplative Action and Active Contemplation

The following is an area of deliberate practice that are underrated by many clinicians. It’s not fanciful, and frankly, quite tedious at first.

A. Contemplative Action:

Park aside some time next week or so to look through your caseload.

i. Who are the ones who terminated therapy prematurely in the face of lack of improvement?

ii. What are your baseline rates of dropout?

iii. For each case, how do you decide if there was improvement or not?

iv. Do you have a system to zoom out and look at all of your past cases?

B. Active Contemplation

i. Solve not just for specifics, but solve for patterns. What can you learn about the people who dropped out from treatment prematurely?

ii. What can you learn about you?

iii. Tax the system before taxing the human. What are some systems in place to help you not only keep track of people who might fall off your radar, but also help you prevent unnecessary dropouts from treatment?

PART II

I. Why People Dropout of Treatment?

I had forgotten that Laura, my friend, had brought her teenage son to see my colleague today. I greeted her in the waiting area and chatted a little while Thomas was in-session.

Several weeks prior, after an unsuccessful series of therapy sessions with another clinician, Laura had asked me to recommend someone in my practice as her son was having difficulties in school. I reckoned my colleague would be of help. And I couldn’t resist finding out what had happened with the previous therapist that prompted the want for a change. So I asked her.

Laura said with a wry smile, “You must have trained her and the team.”

“Ha,” I replied with a tint of nervousness. “Why do you say that?” I asked, not quite sure where this was going.

“She made us do these questionnaires… Tom and I decided before the last session, that we are going to give her high scores for both.”1

“I see.”

She went on to explain.”I don’t think she can take it. She’s asking all these questions about ‘how was the session’ but we don’t want to break her heart—the sessions weren’t going anywhere.”

In essence, Laura and her son has collaboratively decided to breakup with their therapist, but gave her the wrong impression that things were going good, and that the sessions were great.

This could happen to any of us.

This is why even if you are using formal feedback tools in your clinical practice, how you ask for feedback, and how you receive them really matters. It is not an assessment tool, but a conversational catalyst.

Laura later told me that she felt for some reason, the therapist seemed pre-occupied about needing being competent with doing the “right thing,” kept insisting on a particular way of working, and might not be able to handle any sort of feedback about how the session was going.

While the story of Laura of her son is not one that is known as a treatment dropout in clinical research—nor in the eyes of the previous therapist, it is important for us to learn as much as possible what predicts clients making an premature termination.

What is a Dropout?

As mentioned previously in Frontiers Friday #127, a useful working definition employed by most recent research on what constitutes a dropout from psychological treatment is the following:

People who discontinue unilaterally without experiencing reliable improvement.

What are the rates of dropouts in psychotherapy? About 1 in 5 clients dropout. But, as stated in our book Better Results, “there’s a huge variance between studies ranging from of 5% to 70%! Dropout rates are typically higher in child and adolescent population (40-60%).”

Don’t brush off this topic on early termination, even though at first blush, the reasons for a client dropping out of treatment might seem fairly obvious (e.g., client not engaged, lack of motivation, not experiencing any benefit).

From the treatment provider perspective, experiences of client dropping out of therapy can be demoralising. Yes, at times we knee-jerk to putting the onus on clients, but for the most part, therapists feel responsible and experience disappointment, confusion and shame when dropout happens.

If we take the time to examine carefully, we just might be able to pre-empt potential disengagement, address any therapeutic ruptures, and make room to help our clients speak the unspokens with us.

RELATED POST: Reduce negative variance and increase positive variance

What Does Not Contribute to Dropout?

Before we examine the factors that lead to premature termination, let’s look at what the body of research tells us about what doesn’t contribute to dropout.

- Not theoretical orientation difference.

- Not individual or group format.

- Not time-limited treatment.

- Not client’s gender, ethnicity, marital status, employment status and education level.

- Not the provider’s age, gender and ethnicity.

Some years ago, I thought people who are non fee-paying clients2 were more likely to dropout from treatment, and less likely to have good outcomes. Looking at my clinical outcomes over time, this doesn’t appear to be the case.

What Contributes to Dropout?

If factors like our theoretical orientation, clients’ and treatment provider’s demographic factors does not play a part in influencing dropout rates, what does?

Researcher Joshua Swift and Roger Greenberg pulled together factors that seemed to contribute to premature termination from psychotherapy:3

- More chronic conditions (e.g., “personality and eating disorders”)

- Treatment settings. University-based clinics, including psychology department training clinics and university counseling centers, experienced the highest average rates of premature discontinuation. This is likely due to younger clients, lack of investment and perceived credibility due to nil or minimal fees charged, and

- Differences between therapists.

Differences Between Therapists

It is well established that therapist effects accounts for 5-9% of differences in outcomes. To put this into context, even though 5-9% might still seem small, contrast this to differences between models of treatment, which accounts for 0-1% in outcomes.4

Moreover, when researchers scrutinise these percentages, the actual outcomes are dramatic. For instance, the best therapist have a response rate (i.e., clinically significant improvement) of 80% (i.e., 24 out of 30 clients respond to treatment positively), as compared to the least effective therapist with a response rate of 20% (i.e., 6 out of 30 clients respond to treatment positively). In other words, over time, the best therapists helped hundreds more people than the worst.

Then what are the differences between therapists that might account for dropout? Swift and Greenberg suggested that based on their meta-analysis, the treatment providers, age, gender or race did not predict dropouts. They pointed out that one of the other reasons university-based clinics experienced highest average rates of premature discontinuation may also be due to the fact that less experienced trainees providing the services.

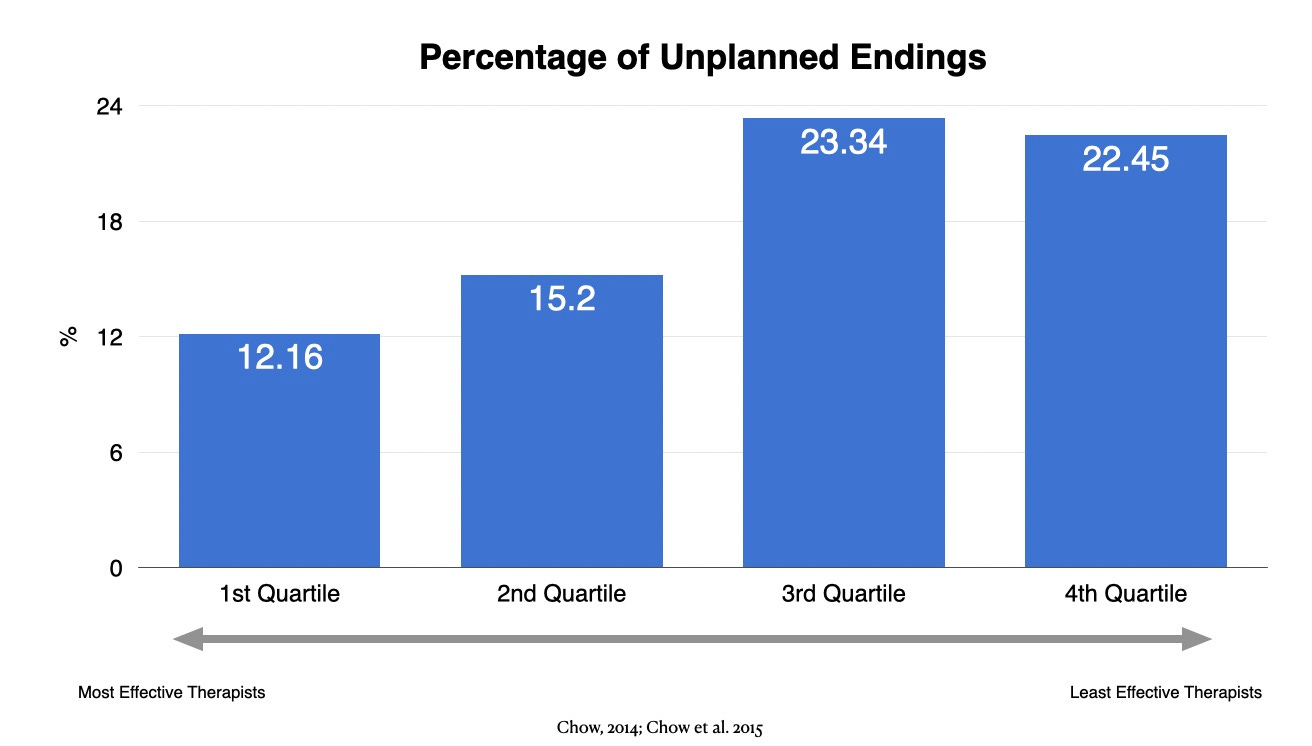

Here’s some other clues about differences between therapists. In my analysis of therapists in the UK who have been systematically collecting outcomes for 5 years (69 therapists; 4580 clients), the number of planned/unplanned endings explained about 65% of the variance between therapists.5 To make sense of these numbers, take a look at the figures below.

On aggregate, the most effective therapists seemed to significantly lower unplanned endings compared to the least effective therapist (12% vs 22%). Conversely, the analysis suggests that most effective therapists have a much higher rate of planned endings than the least effective therapist (73% vs. 27%).

Take Action: Look Close In

What are the implications of all of this information about treatment dropout? What can we do to improve our dropout rates? Here are two areas to consider.

1. Zoom In, and Zoom Out

This week, park aside some time to look through you existing caseload. Who are the people who dropped off your radar and hadn’t experienced reliable improvement? Zoom in and investigate further. Revisit your casenotes if needed.

And then Zoom out. Do you notice any patterns (see this post on Solving for Patterns for some clues. I talked about what I’ve learned from my on outcomes over the years).

2. Deliberate Practice (DP)

This part is often overlooked in the DP process.

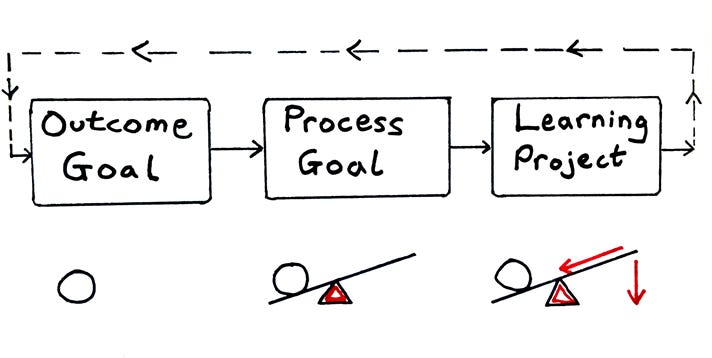

Here’s a framework to help you break it down into manageable chunks. I call this the OPL framework.

Outcome Goal

First, the Outcome goal is the one that we are most intuitively familiar with. What is the end goal that we want to achieve? Saying that we want to improve our effectiveness isn’t enough. For the purposes of our discussion here, it should be framed specifically to the reduction of dorpout rates. In order to do this, you’d need to

a. Figure out the percentage of people who dropout of treatment in your care,

b. Aim for a realistic outcome goal in the near future, and

(note: An understanding of the base rates is useful in this instance. As mentioned, the baserates of dropout is about 20%)

c. After you’ve established the Process and Learning Goals (see below), fix a time point in your calendar to revisit this.

Process Goal

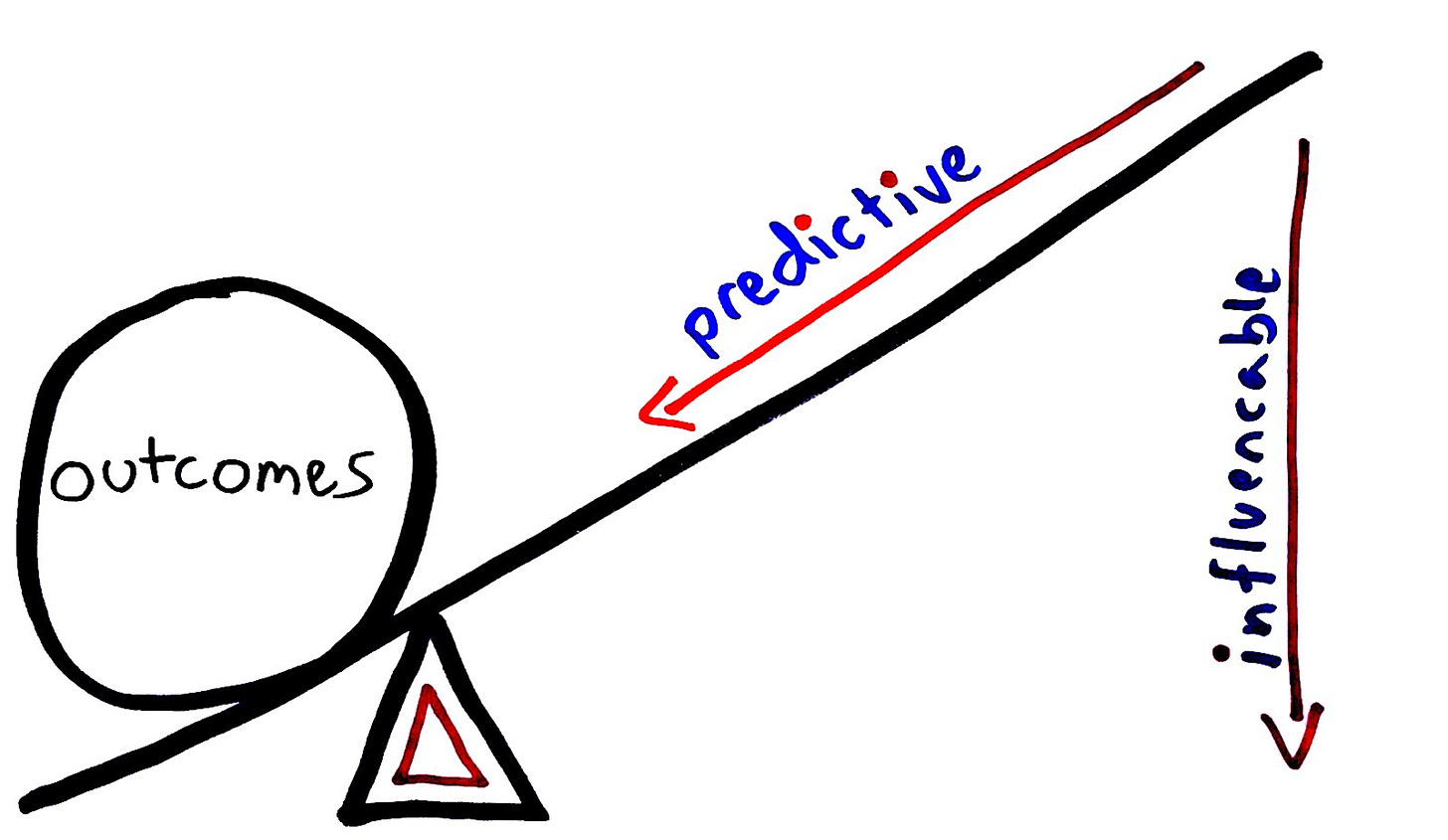

Second, once your outcome goal is defined, we need to figure out the process goal. The process goal is about creating an ongoing system that leads to the outcome goals. A guiding principle of a good process goal is that it must be predictive of influencing the outcome goal, and it must be influenceable i.e., something that you can work on.

A good way to think about what is “predictive” is to turn to what the existing literature on what prevents dropout (see my summary of Swift and Greenberg’s book on Premature Termination in Therapy). Knowing what is truly predictive gives you a good head start.

Next, here are some practical suggestions on what are some influenceable factors to reduce dropout rates:

a. Frequency expectation:

The mere act of specifying duration was associated with lower dropout rates. Most people expect to attend only a few appointments, but if made aware that a greater number of sessions are involved, “they know what to expect and are more likely to follow through with that expectation.”.

Though I do not provide an exact number, I usually say to my clients that we’d meet for just a few sessions to see if this is helpful. Plus, I’d monitor their progress using outcomes measures session-by-session. If things aren’t going in the right direction, it’s my responsibility to tweak/adjust/calibrate in order to better help them. Finally, it’s my job to render myself out of a job.

b. Logistical Concerns:

Don’t forget to address logistical concerns, if any. This could relate to issues with transportation, finances, caregiving responsibilities, etc. We can also use systems to help people with their logistics. For instance, in our group practice, we found that simply having an automated sms reminder 48hrs prior to their appointment dramatically reduced DNAs. The unintended consequence of this was that in some rare occasions, clients arrived at the right time, but one day earlier!

c. Pre-therapy Phase:

It would do everyone good to match unique preferences at the pre-therapy phase, if any. For instance, match someone at the outset if they have specific preferences of seeing a female, someone with a particular spiritual orientation, etc.

“…clients who receive their preferred conditions were between one half and one third less likely to drop out of therapy prematurely compared with clients who did not receive their preferred therapy conditions.”

(Swift & Greenberg, p.85)

Enquire about client’s initial thoughts of expectations on treatment length.

- Address the fact that focus of therapy may change over time, thus treatment length might change.

- Address issues regarding a decline in hope or motivation.

- Therapists are poor judgers of recognising when their clients are getting worse, so, monitor progress systematically, because a client is more likely to dropout if it deviates from expected trajectory and the issue doesn’t get addressed in the here-and-now.

- Monitor engagement. I’ve found that if you are able to pick up even the slightest drop in the alliance ratings, you may have helped address a potential early termination. Unfortunately, when I looked back at my data, there have been occasions when I failed to address these dips, which turned out that these clients did not continue sessions subsequently. One might argue in the absence of measurement, “Well, I ask for feedback all the time.” The thing is, these dips in alliance ratings were typically verbalised as a “yeah, all good. Thanks for the session.” But their alliance ratings, when contrasted from previous sessions, tell a different story. Our job is to pick up the nuance. On those occasions, I failed to.

Learning Goal

Finally, design a learning project. As illustrated above, your learning goals must align with your process goal and your outcome goal. In other words, the question you’d be thinking about should sound something like,

“What do I need to learn at this stage of my development, so that I can influence my process goal, and in turn, impact the outcome goal?”

For the purposes of reducing dropouts, a learning goal could even be “learning how to address treatment expectations at the initial session,” or “systematically eliciting alliance feedback after each session.”

Note: We’ve elaborated on the OPL framework for deliberate practice in greater detail in Chapter 2 of our forthcoming book, The Field Guide to Better Results.

II. Keynote: Engaging the Edges

Finally, here’s a related keynote address I gave a few years ago during the lockdown period, called Engaging the Edges: Connecting with People Who Dropout from Therapy… Before It Happens.

Thanks to the organisers, The Network of Alcohol and other Drugs Agencies (NADA) for making this available.

Starts at 01:00min to 28:39min.

PART III

- 👩👧Meta Analysis of Head-to-Head Comparisons: Treatment Refusal and Premature Termination in Psychotherapy, Pharmacotherapy, and Their Combination

Coming off the heels of their book, Premature Termination in Psychotherapy, as highlighted previously, Joshua Swift and team conducted a head-to-head meta analysis of 186 comparative trials. They wanted to find out if differences exist in treatment refusal and dropout from psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination. Here’s what they found:Key Grafs:- Clients who were assigned to pharmacotherapy were 1.76 times more likely to refuse treatment, and 1.2 times more likely to dropout, compared with clients who were assigned psychotherapy.

- “Pharmacotherapy clients with anorexia/bulimia and depressive disorders dropped out at higher rates compared with psychotherapy clients with these disorders.”

- “No significant difference in rates of treatment refusal and premature termination between the single treatment (pharmacotherapy alone and psychotherapy alone) and the combined treatment (pharmacotherapy plus psychotherapy and psychotherapy plus pill placebo) conditions.”

- Across all studies, an average treatment refusal rate of 8.2% was found (DC: This is important to note. While the figure might seem small, the researchers noted that “it is important to remember that these were clients who already indicated that they were willing to be assigned to any of the treatment conditions.” In other words, this was the percentage of people who first said yes, and then said no.)

- Key (obvious, but not trivial) point: Client preference of types of treatment matter.

- ⭕️ Meta-Analysis: Patient Preference for Psychological vs Pharmacologic Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders

Though not exactly about dropout, this other meta-analysis dovetails with the previous recommendation regarding client preferences:- 75% of adults prefer psychological treatment compared to pharmacological treatment.

- 75% of adults prefer psychological treatment compared to pharmacological treatment.

- 🧪 A Lab Test: A Lab Test and Algorithms for Identifying Clients at Risk for Treatment Failure

I particularly like this study design. I like to use this example in workshops to highlight how we miss the boat.

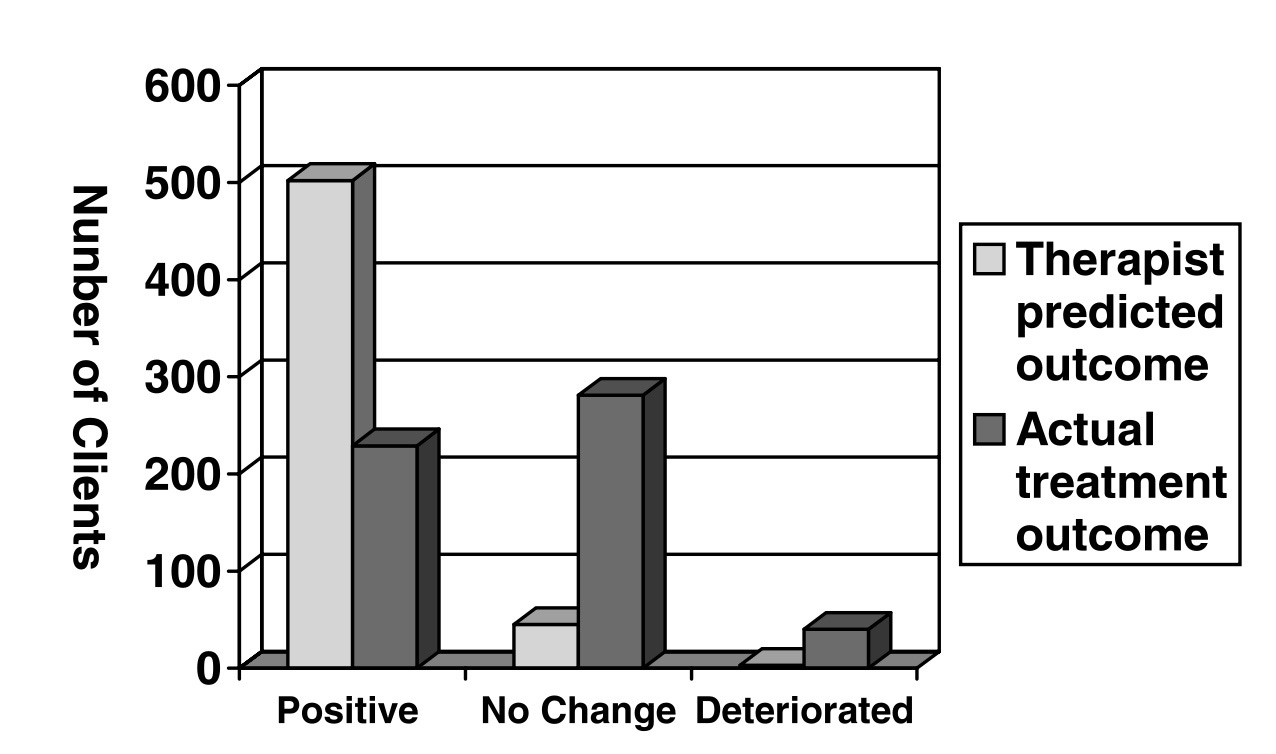

Here’s how the study went:- At the outset, the researchers told a bunch of therapists (N=48) some baserate information, that is, on average, about 8% of people get worse in treatment.

- After treating 550 clients in total, the therapists were asked, how many got worse. The grand total number of clients they predicted got worse was 3.

- In contrast, the actual outcome data indicated that out of the 550 clients, 40 deteriorated by the end of treatment. (Note: This was close to the baserate figure of 8%, compared to 3 out of 550).

- However, out of the 3 the pracittioners predicted to have deteriorated, they were acurrate only with one of the 3 cases!

- The researchers summed up, “We interpret these results as indicating that therapists tend to overpredict improvement and fail to recognize clients who worsen during therapy” (p. 161).

- ⭕️ Meta-Analysis:Are psychotherapies with more dropouts less effective?

At first, this 2018 study hit me as a strange research question. Turns out that the relationship between outcome and dropout is not so well established.

Here’s are the 3 key findings:- Individuals who dropped out began treatment more distressed than those who completed therapy (smalle average effect size),

- Individuals who dropped out of therapy were more distressed at posttreatment than individuals who completed therapy (moderate average effect size) and

- Treatments with higher rates of dropout were also less effective for the treatment completers.

- ⏸ Words Worth Contemplating:

“A little knowledge of the greatest things makes us happier than a lot of knowledge of lesser things. ”

~ Variations attributed to Aristotle and St Thomas Aquinas.

Reflection:

What is your weakest link?

Recent Comments