As a field, we were obsessed with methods, approaches, tools, theoretical orientations, and schools of thought. Money poured into establishing treatment efficacy differences have not yield much fruit; therapists investment in time, effort and money to train in specific models have not demonstrated improvement in our results.

I suspect that one of our key mistakes is a failure to learn first principles, instead of methods.

As to methods, there may be a million and then some, but principles are few. The man who grasps principles can successfully select his own methods. The man who tries methods, ignoring principles, is sure to have trouble.

~ Ralph Waldo Emerson, Essayist and Poet

First principles is about deconstructing to the fundamental truths or origins. Aristotle calls this “the first basis from which a thing is known.” (‘origins’; archai).[1]

For instance, no amount of cooking is going to make a dish with bad ingredients taste good. One the first principles of good cooking is using fresh ingredients. No amount of embellishment to a song is going to make a tune stand out if it does not have a strong melody. One of the first principles of good songwriting is a strong melody.

At this point of my thinking, I view first principles as a set of mental short cuts (i.e., heuristics, or what Nassim Taleb calls “rules of thumb”[2]) that organises the way I think, and subsequently, guide the way I approach a situation (often, a challenging or difficult situation) in therapy.

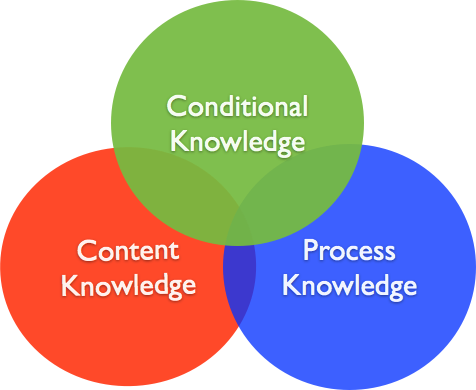

In a previous post, I talked about the the three types of knowledge that we can immerse our appetite for learning.

To recap, content knowledge relates to the clinical theoretical understanding that you have of a client’s presenting concerns (e.g., depression, obsessive compulsive disorder, schizophrenia).

Process knowledge relates to the the moment-by-moment interaction between client and therapist (i.e., what you will say).

Finally, conditional knowledge relates to how you would work differently with someone who is depressed due to bereavement, compared to someone who is also depressed but has a history of domestic violence.

Depending on the phase of our professional development, we would have different levels of focus in these three types of knowledge.

Applying First Principles Thinking

Pulling together the content, process, and conditional knowledge, here is a concrete example of what I mean by first principles on an applied level:

1. When a conflict arises between you and your client and your client gets angry at you:

– First Principle = Disarm by Agreement: Instead of defending your point, disarm the situation by not becoming defensive, or even trying to clarify your point. Rather, take the position of your client’s inner world, and speak from there.

– e.g., “You know, as I think about what you just said, I can’t believe how insensitive I’ve been. You are right. I haven’t been here for you when you needed me most… not wonder you are angry at me”

2. When a conflict between you and your client arises and your client gets angry at herself:

– First Principle = Target of Emotion: Instead of pondering on her self-blame, help your client face the angry she has towards you which she has negated.

– e.g., “Do you notice that when we were facing the issue earlier, you went straight to getting anger at yourself? What if we face the emotion together? Can we invite this into our conversation? What is your feelings towards me when I wasn’t there for you when you needed me most?”

Why do We Need First Principles?

First principles are GROUNDING IDEAS, not GROUND RULES.

First principles organises us with a form, not a formula. A form gives you a rough guide on how to operate; a formula tells you a fixed rule on how you must operate.

First principles are not meant to be formulaic, and it’s not about having stock answers to pull out from your toolkit. First principles provide you mental representations of how to handle a situation, roughly. First principles are about having a compass to guide you on an uncharted terrain with your client; it’s not a detailed roadmap.

Without clear first principles, even though we say we are intentionally taking a “not knowing” position, we behave like we don’t know what to do in every new situation. We say, “we will response to the client’s presentation at that time,” or we say, “It depends.” The truth is, most of the time we do not have a mental model of how to approach especially a challenging situation.

Renowned basketball coach John Wooden says this,

“You win by becoming a better player of the game at large, not by adapting your technique to every new team you face. Your opponent will always be changing; it’s a losing race. But if you master the game, you will have skills and knowledge you need to defeat whoever you face.”[3]

First Principles is a first step at mastering the conversational craft of psychotherapy.

What is NOT a First Principle?

– Case conceptualisation: Case conceptualisation or formulation are not first principles. A first principle will give you not only a rough guide of how to think, but also roughly how to handle a situation (recall content + process + conditional knowledge);

– Algorithm: A first principle is not algorithm. An algorithm provides a list of clearly defined steps on how to approach and solve a situation. Whereas a Principle is a rough mental model to guide you in a somewhat uncharted terrain;

– Rule: A first principle is a grounding idea, not a ground rule. There are rough mental “rules of thumb”;

– Theory: A first principle is not a theory. Theories may be governed by principles, but theories are less of a “good guide” on how to therapeutically engage with a given client. Saying that one of your principles is to be empathic is not a principle. It’s a theoretical idea. A first principle must provide the estimates of HOW to explicate empathy in particular situations.

Before we develop tools and methods, let’s develop first principles. It’s important to note that even though I’ve talked extensively about the implications of deliberate practice in our field, deliberate practice is a methodology, not a goal. Let’s not get caught up with any methods. Once we are able to go to the base of the semantic tree and articulate the first principles, we will have at our disposal an array of different and expansive methods and approaches, far beyond those articulated in psychotherapy schools of thought.

The truth is, first principles thinking is annoying, because unlike a set of clear instructions, or an algorithm, first principles do not spell out what to do each step of the way. Once again, it’s not a detailed map, but a guiding compass. Besides, a map is useless if you don’t know where north is!

Treat first principles as signposts for the journey.

What If I don’t Have Clear Principles?

Most likely, you already have some. It’s probably not been deliberated and explicated consciously.

In any case, it’s time to start developing them. Write them down! (see previous post on the difference between note-taking and note creation)

Stay tuned for the next blog post on Three Ways to Develop First Principles in Your Clinical Practice. In the mean time, I would love to hear what you think about the distinction between first principles and methods, and how you apply this idea into your practice.

Best,

Daryl

Footnotes:

[1] See Terence Irwin’s book, Aristotle’s First Principles

[2] See Nassim Taleb’s book, Antifragile.

[3] John Wooden, A Game Plan for Life, 2009, p.41

Hi Daryl,

Very interesting reading, although I’m left somewhat wondering how one arrives at the principles. For example, ‘Disarm by agreement’, is it that this is an example of a principle one develops oneself or is it a ‘truth’, a self-evident truth that suggests this is always the correct thing to do.

Funnily enough, the way I was trained was based around what the originators of the approach (Human Givens: http://www.hgi.org.uk) called a ‘set of organising ideas’. These, I guess, might be 1st principles. For me, the 1st principles (organising ideas) we were taught to recognise make good sense. E.g:

Human Beings have fundamental needs that need to be met in order that they might thrive.

Human Beings arrive with innate resources that allow them to get their needs met.

Human Beings live in environments.

A failure to get needs met is likely to lead to mental distress.

Recognition of unmet need and addressing the barriers to getting the unmet need met (such as damaged resources) will lead to resolution of the mental distress.

An unhealthy environment will not provide the sustenance for assisting to get one’s needs met.

For me, these are guiding principles, or self-evident truths. They are either true or they are not. I’m happy to accept their truth and then this becomes the compass that can point to ‘true north’.

So, I guess my wonder about this is how does one arrive at one’s principles in the first place.

In my rather poor attempt to be empirical I’ve worked over many years at developing a way of measuring unmet meed and have a measure that’s been in use for several years now, although no validation papers have been published (the PRN-14; can be downloaded at http://www.pragmatictracker.com/measures.php ..just click on the long name). Our data show that there is a strong correlation between reduction in mental distress as measured using standardised tools (e.g. CORE-10) and getting needs met better.

So, I guess I’m looking forward to your next blog…about how to develop one’s 1st principles.

All the best,

Bill

Hi Bill,

so good to hear from you. And yes, it’s similar to what human givens call “organising ideas”

” Client’s unmet emotional needs causes problems” idea is evident in several models of therapy e.g., bill glasser’s reality therapy, Les greenberg et al emotion focused, and HG…

This is a good guiding idea. What i’m trying to articulate is that first principles should not just provide a conceptual guide, but also must inform the therapist on HOW to apply such a theory in conversation.

The other thing is: We need to develop OUR own first principles. As you said, more on that in the next post 🙂

You mentioned, “Our data show that there is a strong correlation between reduction in mental distress as measured using standardised tools (e.g. CORE-10) and getting needs met better.” Love to learn more about the findings!

Best,

Daryl

I think you are really on to something here. I think it’s is hard to speak about. What if you applied the resolution of the client-therapist conflict that you have been exploring to the conflict with themselves that a client brings to therapy. I have come to think that the model is just a vehicle for exploring human beings… like exploring the basketball game through drills. It’s a kind of way in but then you are immersed in the game and learn sensitivities without necessarily knowing how you are learning them.

I don’t think you should pin down what you are saying too quickly in case you miss something.

Gabrielle,

I think you hit on a powerful note! And you are right, I really struggled trying to pin down my thinking behind this idea of first principles (as I’ve mentioned in the Facebook frontiers group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/233495736981548/permalink/563348570662928/)

Can you say a bit more about “I don’t think you should pin down what you are saying too quickly in case you miss something,” as I’m not quite sure what you mean.

thanks again.

Best,

Daryl

I’m not too sure, but sometimes when people get really close to a breakthrough they can’t help but see the concepts and explanations and miss the real transformative view. There’s a beautiful paper that gets me as close as I’ve ever got to experiencing that difference. I’ll email it in case you are interested.

Hi Gabrielle, I got it! Thanks so much. Reminds me of Thomas Merton saying that we shouldn’t be obsessed w the finger pointing to the moon, and instead we should just look at the moon.

Will read the paper, and will get back to you. Thank you so much.

-Daryl

Hi Gabrielle, I found what you’ve sent me is online as well, in case others wanna read it too: http://www.wernererhard.net/thpsource.html

Some parts are hard to follow, but this particular section hits me like a ton of brick!

“Fundamental laws and principles, however, cannot be deduced. One knows them by creating them from nothing, out of one’s Self. One does not arrive at fundamental laws and principles as a function of what is already known. Such laws and principles do not merely explain; they ILLUMINATE.” (I love this.)

“They do not merely add to what we know; they create a new space in which knowing can occur” (emphasis mine).

“The test of whether we are dealing with fundamental laws and principles, or with mere reasons and explanations, is whether there is a shift from controversy, frustration, and gesturing, to mastery, motion, and completion.”

Thanks for sharing this Gabrielle!

Damn I love this stuff… At the same time I find it so infuriating because I want to be told what to do. I often find myself gravitating towards rules and explanations, and approaching ideas in a “dissecting” sort of manner until they make sense to me. Often this seems to come at the cost of understanding “the bigger picture,” which I think comes through in my presentations which seem to leave people thinking: And now what?

I’ve also found my “dissecting” approach to be of little help in my attempts at relating to clients during therapy, where it seems to get me offside on occasion and draws me into a very fragile ivory tower where I must know and have the “right” explanations.

What I really enjoyed about the DCT trials, was being given general ideas about how to approach the interaction and then afterwards, getting feedback about how my application of the idea came across. I was not told what to do explicitly, but I was told how what I articulated, related to the general principle I was asked to adopt (e.g. disarm by disagreement).

This leaves me thinking about my attempts at developing my mountain biking skills, where someone who’s helping with this says: “Stop trying to make the bike do things you’ve watched in videos, and instead, relax and get a feeling for what the bike is doing.” I’m then told, that as I develop a better understanding of the bike in different terrain, what I’m trying to do now (not very well and with great expenditure of energy) will come as a matter of course. Funnily enough, something similar came up in supervision, where the feedback I got was to try and go with the session more, and the client, rather than exerting as much effort at steering it into a particular direction. I can then expend my energy more at tending to the client during the session, rather than the topics or ideas I want to cover.

I’m not sure whether, or how, this exactly relates to what you’re saying here Daryl. But I enjoy writing down my musings nonetheless. As usual, great stuff!

Cheers, Eeuwe! I love your mountain biking example. We watch too much of “end results” and fail to see what are the steps leading to that.

I’m still struggling w this whole first principles idea. Take for example, for a musician, there’s an assumption that you must be fully grounded in musical theory to be able to improvise well. I disagree. And there are many evidence of renowned musicians who don’t have solid musical theory. Instead, they gasp the key principles of music composition and improvisation.

Going back to your mountain bike example is a usual one to think about “Getting a feel” for the bike…

I love your reflection, Eeuwe. Thanks for sharing them.

Best,

Daryl