You may have seen that there’s been a surge in books about deliberate practice (DP) in psychotherapy.

There is DP for CBT, DP for EFT, DP for DBT, DP for IPT, DP for MI…

The list goes on.

I have nothing against any model-specific approaches. Personally, I found myself drawn to systemic thinking and experiential-based approaches. More recently, I found myself drawn back to depth psychology. Specific approaches offer specific metaphors. Metaphors represent and point to realities.

However, I’m not so sure that it makes sense to think about deliberate practice (DP) for specific schools of therapy.

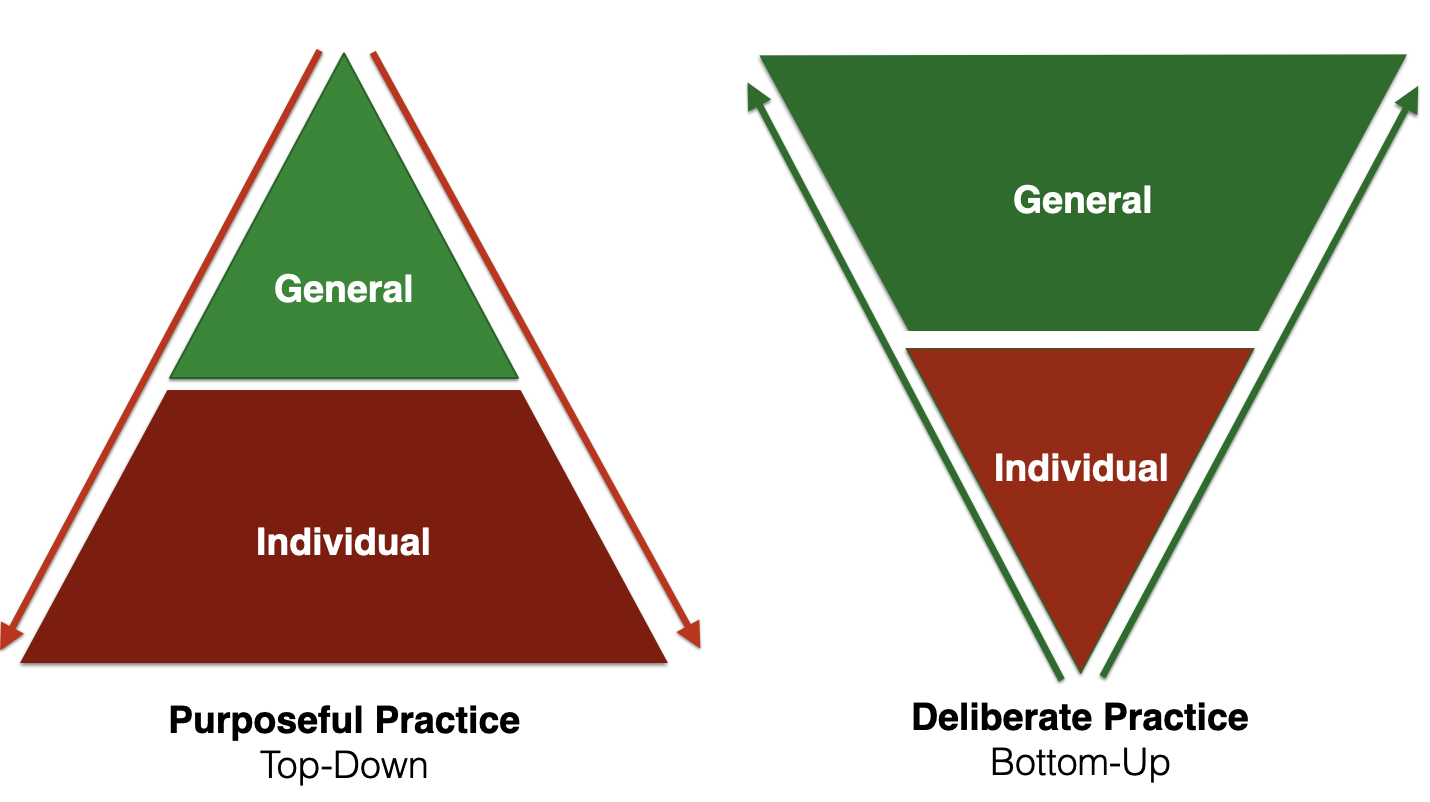

To me and my co-authors, it sounds more like purposeful practice (PP).

PP is more about competence.

DP, on the other hand, is more about excellence.

RELATED:

See this post Deliberate Practice is Not Purposeful Practice.

—

There is a place for PP. Maybe there is a place to get better at specific modalities.

However, that is what our field has been doing for the last 60 years—and it hasn’t gotten us very far.

The cumulative evidence suggests that there has been minimal advancement in enhancing client outcomes. Not only that differences between models account for 0-1% of outcomes[1], competency in specific modalities or adhering to specific protocols contribute nothing to outcome.[2]

When I think back of various workshops on specific schools of thought that I’ve attended, be it in ACT, CBT, EFT, Schema therapy, most trainers tell me to stick to the technique, so that I can get better at it. The consequence of this communicates more of compliance than on following your curiosity.

Having said that, purposeful practice is appealing, both for clinicians and educators. Why? For two reasons. PP provides

- Structure, and

- Scalability.

First, the affordance of structure in specific models provides a clear pathway on what to work on, how to get better at it, and even a list of exercises you can do to get good at it, based on the assigned objectives and competency grading given.

Second, you can rinse and repeat. The stability allows more therapist to learn this at scale.

We tend to conflate structure with models. Therapists have a tendency to seek structure by learning a specific approach. I think that is limiting. I argue that we have to learn how to structure our sessions beyond specific modality.

By zooming in prematurely to a specific model, you end up rigid in your method, coupled with a lack of grounding first principles to guide what you do. (I’ve talked about the importance of structure elsewhere).

In terms of scalability of DP, there is no so straightforward ‘factory’ solution because, as you might recall from previous issues, DP is highly individualised (see the top right pyramid).

If you jump too quickly into ‘practice exercises’ without first figuring out if this is the right thing for you to work on (i.e., course learning objectives vs. individualised learning objectives), you could end up expending energy without actually translating to specific improvements (i.e., repetition vs. successive refinement).

Another way of thinking about the difference between PP and DP is its general pedagogy. The method of teaching in PP is predominantly top-down (i.e., what you should be learning), whereas in DP, the emphasis is more bottom-up (i.e., figuring out where each therapist’s existing ability is, tapping into their native wisdom and going from there).

Before we go further, here is an overview table for comparison:

Table Comparing Purposeful Practice and Deliberate Practice.

By analogy, if you were a musician, it’s much easier to practice scales on a piano than getting good at songcraft. With scales, the target is well-defined. You keep working at it and you get the result. With writing better songs, it’s less well-defined, it’s subjective, but you can work at it. You might not even be technically proficient, and still improve at song-craft.

Think of The Beatles. None of the fab four were technically proficient, nor did they even seem to know what chords they were playing at times.

In therapy, it’s much easier to work at thought challenging than it is to help a client have an impactful experience in the session.

This is because, therapy exists in what Robin Hogarth calls ‘wicked’ environment, not a ‘kind’ environment.

Kind Environment

Kind environments are when the feedback loop for the target of learning and the impact of performance are clear. Examples of kind environments include golf, chess, bowling, weightlifting and school homework.

Deliberate practice in the field of psychotherapy is not like weightlifting, where the more you do, the stronger your psychotherapeutic muscles become.

Neither is it like golf, where if you spend more time to improve your putting, you will likely improve your game.

Neither is it like chess. Though it is a game with highly complex strategies, it’s parameters are well-defined; its objective is easy to measure.

In short, weightlifting, golf and chess operate under kind environments.

Wicked Environment

On the other hand, a “Wicked Environment” is where the rules of the context are often unclear, and the feedback loop for the target of learning and the impact on the performances are delayed, inaccurate, or both. Examples of wicked environments include poker, soccer, medicine, and life.

When we practice as if we are in a kind environment, we run the risk of our efforts looking like #4, where our learning efforts does not translate in our targeted naturalistic setting.

If we reshape our efforts and design for learning in a wicked environment, we stand a fighting chance for our professional development efforts to impact our clients lives. If continue to think we are in a kind environment, we are likely to make very little progress in the end.

The task of DP is to seek not just what’s right, but what’s right for you i.e., what you need to work on to get at your growth edge.

Can DP Make Things Worse?

Even if we make little progress, can DP actually make things worse?

In a 2024 Swedish study, an eight-week RCT manualised DP course found that the DP group experienced a decrease in alliance.

Take a look at this graph.

Why is this the case?

Why Engage in DP?

Maybe I’ve been starring at this for too long. Maybe I’m missing something about the merits of “DP” for specific models. I’m prepare to change my mind about this. After all, we are at an early stage of development for DP in our field, and there’s so much to discover and make progress in.[3]

I’m not wedded to concepts like DP. The most important thing is not to lose track of what is the most important thing.

So what’s the most important thing? For me, it is this:

“Are my efforts in learning and development actually helping those whom I seek to serve?”

Recent Comments