How to reduce dropouts from psychotherapy and inviting therapists to bring everything to bear.

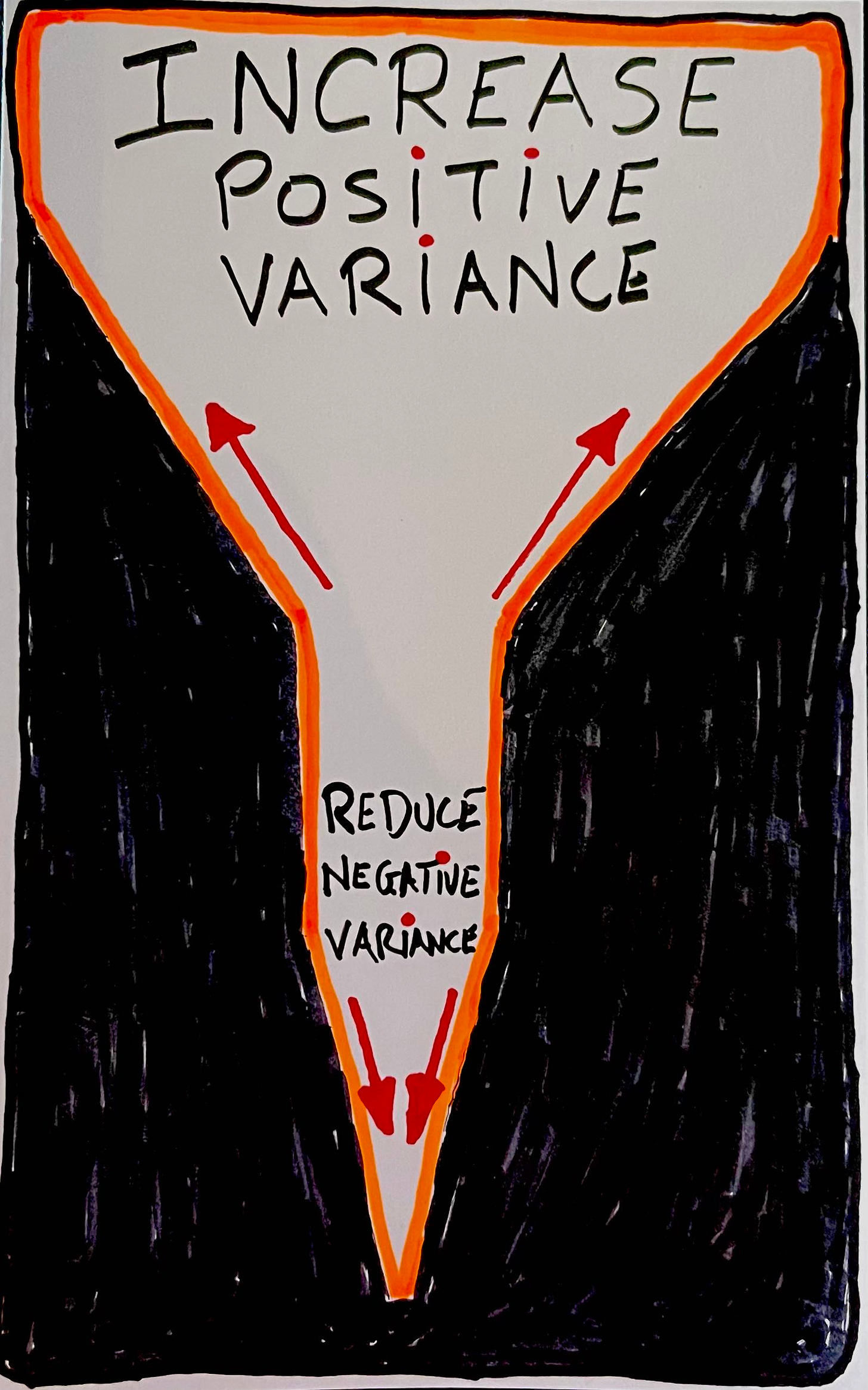

Reduce negative variance and increase positive variance

There are two sides. Both sides are of value and require a different perspective. Let’s call them Negative Variance and Positive Variance.

Reduce Negative Variance

The first is to address how we can reduce the odds of people dropping out of treatment without experiencing gains, unplanned endings of therapy, and deterioration.

Reducing negative variance requires us to first, square with the facts. Take for example, even though you might be admitted to a hospital for medical treatment, there is also a chance of you getting sick from being there.

Here is surgeon Atul Gawande on the realities of intensive care1,

At any point, we are as apt to harm as we are to heal. Line infections are so common that they are considered a routine complication. ICUs put five million lines into patients each year, and national statistics show that after ten days 4 percent of those lines become infected. Line infections occur in eighty thousand people a year in the United States and are fatal between 5 and 28 percent of the time, depending on how sick one is at the start. Those who survive line infections spend on average a week longer in intensive care.

And this is just one of the many risks. Gawande provides a few more examples,

After ten days with a urinary catheter, 4 percent of American ICU patients develop a bladder infection. After ten days on a ventilator, 6 percent develop bacterial pneumonia, resulting in death 40 to 45 percent of the time. All in all, about half of ICU patients end up experiencing a serious complication, and once that occurs the chances of survival drop sharply.

When we are presented with such statistics, it is tempting to point the finger and engage in the blame-game of individuals who fail to keep the Hippocratic Oath, or wave our hands and say that’s just the way it is. As Gawande points out, the issue is less to do with ignorance, but ineptitude.

Ignorance refers to a lack of knowledge or information, and can be resolved by acquiring the relevant knowledge.

Ineptitude, on the other hand, is more about a lack of skill and ability to perform a relevant task.

Our great struggle in medicine these days is not just with ignorance and uncertainty. It’s also with complexity: how much you have to make sure you have in your head and think about. There are a thousand ways things can go wrong.

How does all of this relate to people dropping out of psychotherapy prematurely?

Most of us fail to pick up the signs that people are disengaged from therapy or even deteriorate while in our care.

Here are two questions to consider:

1. What is your best guess of the rates of people who drop out of treatment?

2. What is your best guess of the rates of people who get worse in treatment?

Answers:

1. In the face of not experiencing any reliable improvement, it is estimated 20-22% of people unilaterally terminate treatment.2 In other words, for every 10 clients that you see, 2 of them are likely to prematurely discontinue treatment in the face of lack of improvement.3 More sobering, if you are working with child and adolescence, the rates are even higher, between 40-60%!

2. And what about deterioration rates? The percentage of people who get worse while in treatment is about 5-10%. The real question is, do you know who actually is getting worse?

Increase Positive Variance

The flipside to reducing negative variance is to increase positive variance. What I mean by this is to increase the various possibilities of how one can co-construct a good outcome for a given client, at any given point in time. Instead of trying to homogenise a particular type of treatment for specific issues, we should encourage therapists to flex, adapt and be highly responsive to each unique person that presents in their clinical practice.

A therapist is not a bot dispensing manualised treatments to each person that walks into their office—AIs can do this. Instead, like a jazz musician listening intently to what the other musicians bring to the improvisational performance, they part-take in the therapeutic musical conversation one step at a time. This back-and-forth process can’t be seem ahead of time—that what improvisation means, not yet seen ahead of time—but guided by the aim of bringing out the best in each other.

Some of us are schooled into a false security about empirically supported therapies (ESTs), thinking that since there is a research backing, what we call “evidenced-based,” we end up believing that there is a “best” way to work with a person, given what the clinical presentation is, devoid of who actually is the person sitting front of you.

As such, we are prone to make a critical mistake called ecological fallacy.

Ecological fallacy occurs when we mistakenly make inferences about an individual based on an aggregate information about a group.

In our forthcoming edited book, The Field Guide to Better Results, researchers Joshua Swift and Jesse Owen provides a useful example for us to consider:

For example, a research study could be conducted with 100 female clients over the age of 70 with generalized anxiety disorder. After the administration of a specific 12-week treatment, 85% of them show clinically significant change. Now, a 75-year-old woman with generalized anxiety disorder comes into a therapist’s office seeking help, and the therapist decides to use that research-supported 12-week treatment.

Make your best guess as to the chance of treatment success for this particular 75-year-old woman with GAD?

Here’s Swift and Owen again:

Some might guess that the chance of treatment success for this woman is 85%; however, her chance of recovery is actually unknown. There is no way to tell if she had been in the research study on the treatment, if she would have been one of the 85% who recovered or one of the 15% who did not.**

And here’s when the research applied might start to make sense:

If the same therapist were to apply this treatment to 100 women over the age of 70 over the course of a year, we could assume that around 85% of them would recover and 15% would not. But, we would have no idea which individual woman would fall into which category.

In other words, don’t be misled by “averages.” Design a therapeutic enterprise that fits the individual, not the average. There is no such thing as an “average” person.

Solutions to Reduce Negative Variance

Here are some ideas to consider in order to prevent dropout from the treatment process:

- Addressing lack of treatment gains:

Pioneer researcher in outcome monitoring Michael Lambert have been pointing us in this direction for a long time. We got to systematically monitor outcomes, one client a time, one session at a time.

Specifically, the lack of any improvements at the early stages of treatment should at least give us pause, to reconsider and discuss if we should continue the way we have been. - Addressing lack of engagement:

While some might take a longer time to experience treatment gains, a lack of engagement is a significant indicator to take heed. More specifically, a decrease in engagement levels from one session to the next are very markers.

In my clinical practice, I’ve noticed that even a slight dip in alliance ratings may indicate something. The key is to be able to pick that up and recalibrate. I have a simple system in place: I make the graph containing the session-by-session outcome and engagement trajectory visible to the client and I. I know, it sounds ridiculously mundane. But the very act of make the graphs visible, it has really helped me in many instances. When I revisited some of my caseloads on people, who dropped out from treatment, lo and behold, several had a drop in the Session Rating Scale (SRS). The trouble was, I failed to address it, thinking it was just a slight dip

In this podcast episode, I talked about when things are visible, it becomes visercal. - Engagement of caregivers:

This third suggestion relates to working with the younger population. I’ve found that engaging with the young person and their parents or carers to be highly valuable.

Oftentimes, parents drive their kids to therapy, and are seated outside in the waiting area. For the most part, parents are wanting to know how to better relate with this child. Plus, if a parent does not know how things are progressing, or worse, has no clue if things are improving or not, the chances of premature ending of therapy increases. This is why when working with child and adolescence, it is highly useful to not only get the child’s rating of their wellbeing, but also the carer’s view of how the child is doing. Often, especially at the initial stages, the ratings are different from each other. This is a rich catalyst for the conversation. In sessions down the road, even if you don’t have the parent in at every session, getting the caregiver’s perspective of the youth’s wellbeing is invaluable. - Pre-emptive safety nets:

Finally, simply pre-empting the potentials of disengagement early on can help. For example, at the initial session, I not only explain why I track their outcomes and engagement levels in each session, I also make it clear that if things aren’t improving, the onus is on me, the clinician, to tweak and adjust we go along. Plus, sometimes life gets busy and chaotic, and that they might miss an appointment and as things build up, they might forget about re-scheduling another session. I would ask if they are ok for me to contact them if I have not heard from them in 2 months. It is not for me to pressure them to continue therapy, but rather just as a check-in call. Most people opt-in for this.

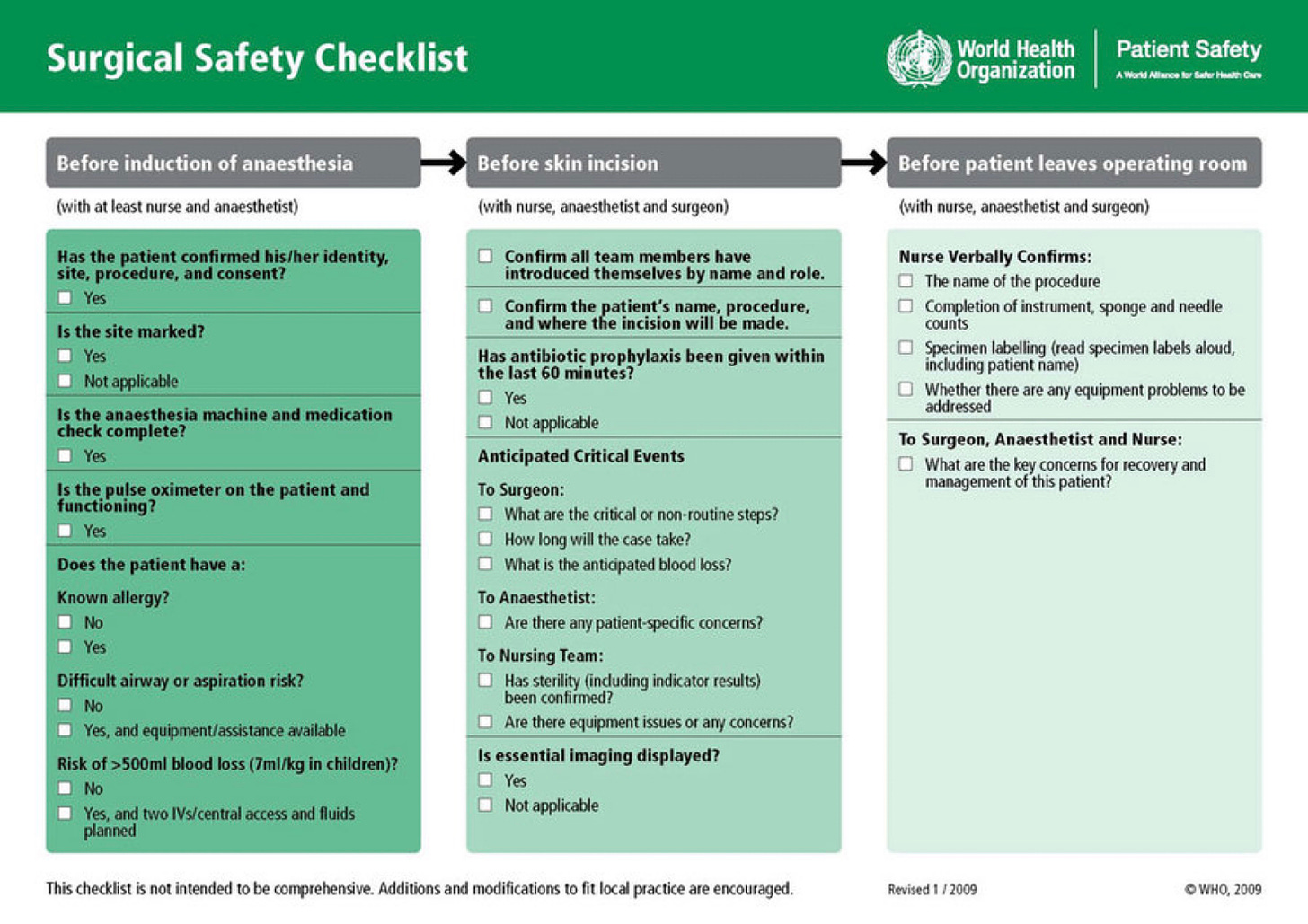

Systematically monitoring outcomes is also form of safety net. Recall Atul Gawande from his reports of infection rates in hospitals. Learning from a chance visit to Boeing and understanding how things work, he couldn’t help but notice how “they fall back on checklists.”

He and his team were able to conduct a research experiment . With a shoestring budget from WHO, they developed a “bedside aide” i.e., surgical safety checklist. They brought this two-min checklist (see below) into the operating rooms in 4 developed and 4 developing countries.

Here’s what Gawande and his team found:

The simple multi-disciplinary team’s use of the checklist helped reduced major complications for surgical patients by 36 percent after introduction, and mortality rates fell by 47 percent!

This is staggering results given the simple implementation of a checklist.

Despite the positive results, 20 percent of doctors in the eight hospitals were not keen to continue using the checklist. However, according to Gawande, “They said, ‘This is a waste of my time, I don’t think it makes any difference.’ And then we asked them, ‘If you were to have an operation, would you want the checklist?’ Ninety-four percent wanted the checklist.”

Solutions to Increase Positive Variance

Now that we’ve addressed some ways to prevent dropouts, let’s address how we can increase positive variance:

- Bring all of you into the treatment process:

Don’t be confined to thinking solely in treatment models. It’s not just about being eclectic and integrative. It’s about bringing all of you to be of service. Maybe it’s your knowledge coming from skateboarding that will resonate with a particular youth. Or maybe it’s your spiritual upbringing that can serve as a useful metaphor to a client who holds a spiritual belief to his existential depression. Or maybe it’s you becoming a parent that has shifted your perspective that could help another new parent.Can we allow ourselves to bring everything to bear, and bow to be of service of the other, without getting caught up in our minds if this is adhering to ACT, EMDR, Schema, or any other acronym of psychotherapies?As most season practitioner will attest, it’s a different an approach for different folks.This is one of the unique professions that require us to bring our personhood into the profession-hood. If you stay too clinical, clients can feel your de-tachment. Your attempt to be “professional” can create a feeling of keeping them at arm’s length. This can be wounding, especially when they are pouring their hearts out to you. - Tap into the client’s world:

Our client’s belief systems, preferences, worldviews and sparks play a huge role in the success of treatment. Our task is to figure out what they are and to tap into them as a wellspring of life-giving forces.

We can tap into sports and peak performance metaphors if your client is highly athletic. We can tap into musical metaphors if your client immerses herself in music. We can tap into spiritual resources if your client is religious.

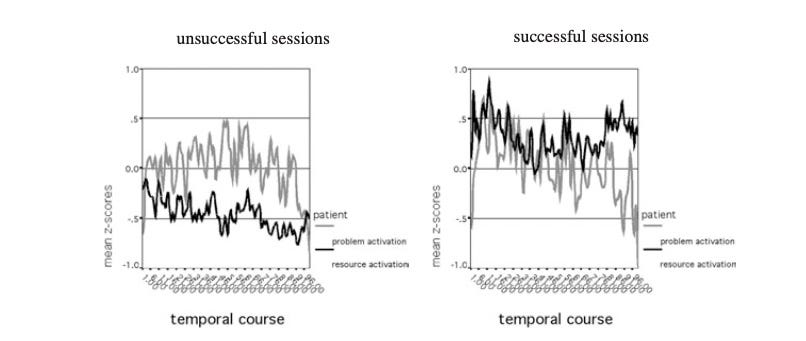

In an intriguing paper by Daniel Gasman and the late Klaus Grawe from the University of Bern, the authors and their assistance combed through 120 videotaped sessions and analysed minute by minute interaction between the client and therapists. They found that problem activation alone does not lead to a good therapy outcome. The degree of resource activation (i.e., strengths, relational and individual resources), however, distinguished unsuccessful therapies significantly from therapies with moderate and high outcome.4

Here are some ideas of questions we can ask as invitations enter into our client’s world:

What do you really care about?

What makes you come alive?

Who has been a significant figure in your life?

What do you do for fun? And why?

For more related to tapping into your client’s world, see “Take Note of These 4 Perennial Factors of Your Clients.”

3. Be willing to be altered:

Finally, we must be willing to change our minds. If the jazz musician pre-determines what he’s gonna play on an improvisational stage, he runs the risk of hyper-focusing on himself. His virtuosity becomes a liability. He will find himself unable to listen and response to the other players.

If we can be altered by what the person in front of us is saying, we can then be moved by how their heart is speaking, and in turn, we can become more deeply engaged with them in the process. After all, even while each party may have differing ideas, the task is for you and your client to become of one mind.For more on this, read “To Be Altered.”

Bricolage

The practice of psychotherapy is not like the practice of medicine. Though we yearn for greater distinctions, diagnoses and clinical treatment pathways of what we should do to alleviate suffering, the human psyche is made of a different fabric. The therapeutic endeavor is like bricolage, we have to use whatever materials available to create a work of art. Every piece, is none like the other.

We are invited to co-construct significant moments with our clients, to figure out where they are and where they want to go. We might not see completely what’s ahead, but as Ted Gioia points out about music improvisation:

The improviser may be unable to look ahead at what he is going to play, but he can look behind at what he has just played, thus each new musical phrase can be shaped with relation to what has gone before. He creates his form retrospectively.

As we’ve pointed out at the beginning, there are two sides. One, we have to do what we can to prevent un-necessary dropouts from treatment, and second, we must encourage every practitioner to bring everything to bear in helping their clients, one person at a time, one session at a time.

For more on the topic of dropout, stay tuned to Frontiers Friday as I’d provide useful recommendations in the coming weeks.

Question: Do you know your base-rates of people who dropout of treatment?

Daryl Chow Ph.D. is the author of The First Kiss, co-author of Better Results, and The Write to Recovery, Creating Impact, and the forthcoming book The Field Guide to Better Results.

The Field Guide to Better Results is coming out soon on 23rd of May’23!

1 From Atul Gawande’s book, The Checklist Manifesto.

2 See Swift, J. K., Greenberg, R. P., Tompkins, K. A., & Parkin, S. R. (2017). Treatment refusal and premature termination in psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and their combination: A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons. Psychotherapy, 54(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000104

3 Even though the base rates for people dropping out of treatment is between 20-20%, there’s a huge variance between studies ranging from of 5% to 70%!

4 Gassmann, D., & Grawe, K. (2006). General Change Mechanisms: The Relation Between Problem Activation and Resource Activation in Successful and Unsuccessful Therapeutic Interactions. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(1), 1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cpp.442

2 Responses

[…] Reduce negative variance and increase positive variance […]

[…] Here’s a related post: Increase Positive Variance and Decrease Negative Variance. […]