The Rule of Three in Performing Arts, Photography and Music.

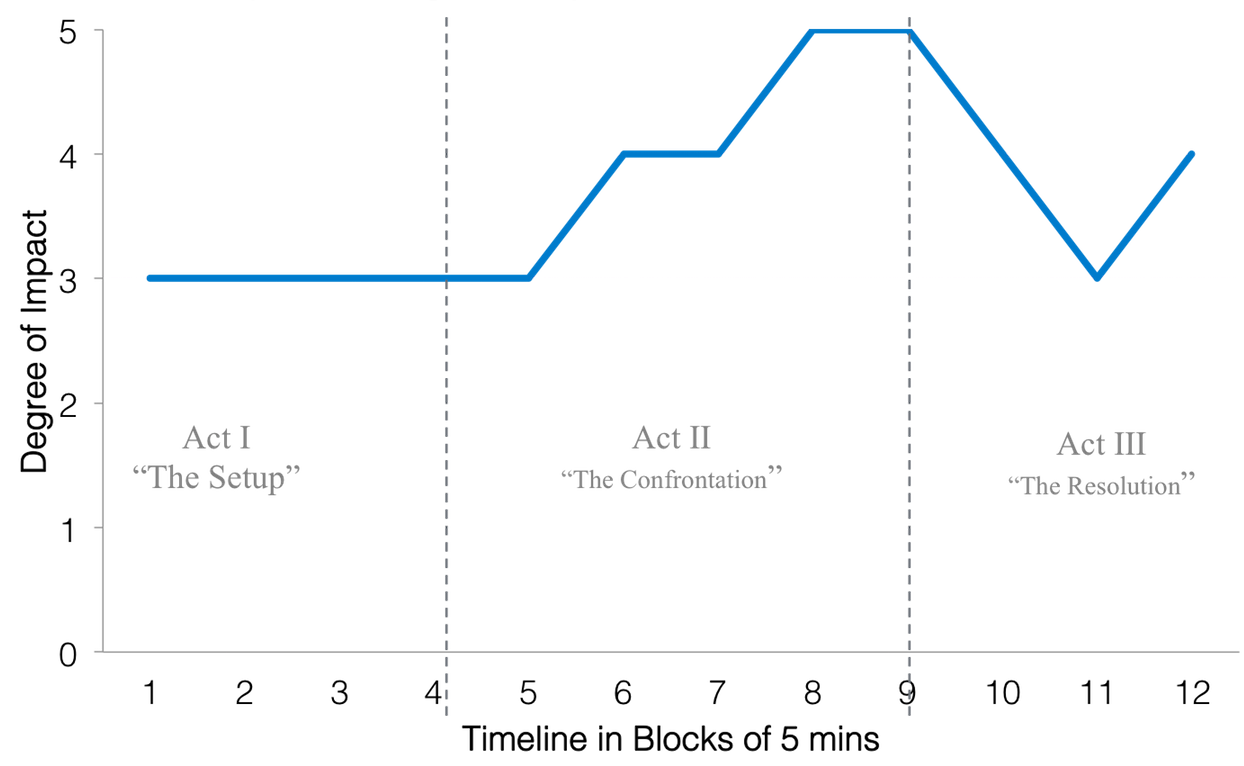

One of the primary ways to think about how you structure your therapy hour is to think in three parts.

In the performing arts, we call this the 3 Acts.

In storytelling, a well-crafted narrative arch takes you on a gripping journey (If this interests you, Shawn Coyne’s The Story Grid is an excellent book on this).

In photography, not every object needs to be dead centre. The Rule of Thirds is a compositional guideline to help you position your elements for a better composition. (After I learned about this principle, even though I’m not a professional photographer, my pictures completely changed. Here’s more on the rule of thirds.)

In music, the rule also applies in a different way (i.e., the amount of times you should repeat the idea without causing over repetition, as too much of a good thing is no longer a good thing. If this interests you, watch this).

You might say that there are countless examples in movies, stories, photos, and songwriting that break this rule of thirds. That’s true. But when it comes to how to not only structuring your therapy hour as a therapist, but also thinking about how you can improve, learning to think in thirds is a really helpful scaffold to have in your mind. After all, the aim of a scaffold is not to have the best scaffold per se, but to have a stable structure to help you build what you want to build.

The Rule of Three in Psychotherapy

In its simplest form, thinking in thirds is about having a beginning, a middle and an end.

In more specific terms for the practice of psychotherapy, the rule of threes can be described as the following:

- An Invitational Beginning,

- Deepening the Process, &

- Resolution.

Here’s what I mean about the first stage:

An Invitational Beginning

The beginning of a therapeutic encounter is really an invitation to a different space and time. We like to say that we “hold space” for the other, and the upcoming 60 mins is a distinct ground. I would even go further and say that it should be treat as sacred grounds. The four walls in our office become a vessel to behold the emotions, heartaches and troubles, as well as growth and development that one experiences in their inner and outer lives.

But the invitation to develop a shared focus is crucial. Without a sense of directionality, it’s easy for the conversation to go to places that might not lead to a healing outcome.

The setup is to open the conversation with intent, focus and directionality. If the client doesn not have a clear sense of what to work on, then part of the process is to figure that out conjointly. Because sometimes the goal is to figure out the goal.

Here are 3 different hats we might end up wearing in ACT I:

- The Meanderer

The Meanderer is someone who lets the client go to tell their story. This is not a bad thing, especially at the initial sessions. In fact, at the beginning of a session, it is welcomed by the client to have some small talk.

However, it is important to take a step further. If you have been in clinical practice, you’d know what I’m talking about, that it’s quite possible to let someone go on and on and later realise that either this was going nowhere, or worse, at the end of the therapy hour, you realise that what they’ve talked about in the last 59 mins was vaguely related to the reasons for coming to therapy!

It’s easy to be swept by wherever the wind blows.

I recall a particular client in our first session. We talked alot about her backstory, her failed relationships and experiences of trauma.

At the end of the session, I asked her to provide me some feedback about her experience of the session using the Session Rating Scale (SRS; watch this video about How to Elicit Nuanced Feedback), even though she rated 3 out of the 4 items as 9-9.5 out of 10, on the Goals and Topics, she rated it like a 6.5.

I was taken aback, because I thought we covered some meaningful grounds.

When I asked her about it, she said that she wanted to talk about one thing that she hadn’t brought up: Her recent abortion.

We spoke briefly about this, but I soon learned that there were complex tones of loss, abandonment, guilt and shame. We made it a priority to make room for this topic in our next session. - The Rigid Behaviourist

Sometimes the word “goals” trigger weird associations of corporate-speak and sports metaphor.

The truth is, not everything can be boiled down to a “SMART goal” (specific, measurable, actionable/achievable, relevant, and time-bound).

If we take a Rigid Behaviourist approach, we can become reductionist and even invalidating to the human experience.

A therapist once told me that she noticed in her own actions in therapy that when she became time-pressured, overworked, and seeing back-to-back clients, she became rigid and wanting to “cut to the chase” with her clients. So she inadvertently reduced small talk at the beginning, and would end up becoming overly prescriptive at the end.

That said, there are occasions when we have to be less abstract and more specific with our behavioural recommendations between-sessions. But you don’t want to be rigid and operating algorithmically [1]; you want to stay nimble, open and flexible. - The Focused

The Focused therapist is one who is able to think in terms of therapeutic aims, while staying flexible to the evolving needs and directionality as it unfolds.

The Focused therapist knows how to play with their lens of focus, i.e., going wide, going deeper.

In the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice (TDPA; Chow & Miller, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2022) worksheets that we’ve developed to help therapists in their deliberate practice [2] , it is worth noting that four of the questions were

i. How do you start a first session?

ii. How do you start subsequent sessions?

iii. How do you establish goal consensus in the first/subsequent sessions?

iv. How do you help a client who has no clear goals in therapy?

Turns out that these are highly important questions for us to develop clear mental models on how we make this elements come alive in therapy.

Developing an effective focus is crucial not just in the initial session, but also for every step of the way. Focus may need to change as things change in the person’s life.

The Focused therapist needs to help steer the sailboat. We can’t control the wind, but we need to consistently check on

i. Where are we, and

ii. Where are we going?

This is why I build the Structure and Impact course.

Leave a comment

Structure and Impact Course

Learning to develop a structure of your own is a skill that every therapist should have. It’s pretty hard to build a building without a scaffold.

As far as I’m aware, this is the first training available on helping you shape the arch of therapy to make it come alive.

For more about this course and start dates, check out this link.

Footnotes:

[1] Robots can deliver algorithmic, manualised therapy. Humans should do humanised therapy.

[2] The upcoming Field Guide to Better Results book deconstructs the entire TDPA with inputs from other leading researchers and authors. Slated to be released in 2023. For now, if you are interested in the TDPA worksheets, drop me an email.

3 Responses

[…] Part I of Thinking in Thirds, I talked about the rule of three in various domains like the performing arts, storytelling and […]

[…] the previous 2 parts on Thinking in Thirds, I’ve detailed about the process of Stage 1 of creating an invitational beginning and Stage 2 of deepening the process in the therapy […]

[…] From My Desk: Thinking in ThirdsPart I: The Rule of ThreePart II: Going DeeperPart III: Closing the SessionHere’s an archive based on a 3-part series that […]