“I always wanted to be someone. Now I think I should have been more specific.”

~Comedian Lily Tomlin

One of the most rudimentary, yet the most difficult thing to do in your professional development is to be specific.

As a culture, we are obsessed with “How to’s”. Do a search on Amazon, and you’d yield close to 100,000 self-help books like “How to Change Your Life in the Next 15 minutes,” the classic “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” and “How to Be Happy,” etc.

The unresolved problem is, we fail to identify What to work on before the How.

Skipping this step of well-defining and specifying the component parts of what to work on that has leverage on improving our situation is like trying to be a writer without knowing how to spell. Sal khan, founder of Khan Academy shines a light at the inherent issue: We go after complex techniques and so-called advanced skills, and lose sight of working at the grammar i.e., fundamentals.

Sal speaks on this issue regarding standardised testing in education:

“On that test, maybe I get a 75 percent, maybe you get a 90 percent, maybe you get a 95 percent. And even though the test identified gaps in our knowledge, I didn’t know 25 percent of the material. Even the A student, what was the five percent they didn’t know?

Even though we’ve identified the gaps, the whole class will then move on to the next subject, probably a more advanced subject that’s going to build on those gaps. It might be logarithms or negative exponents. And that process continues, and you immediately start to realize how strange this is. I didn’t know 25 percent of the more foundational thing, and now I’m being pushed to the more advanced thing. And this will continue for months, years, all the way until at some point, I might be in an algebra class or trigonometry class and I hit a wall. And it’s not because algebra is fundamentally difficult or because the student isn’t bright. It’s because I’m seeing an equation and they’re dealing with exponents and that 30 percent that I didn’t know is showing up. And then I start to disengage.

To appreciate how absurd that is, imagine if we did other things in our life that way. Say, home-building.

So we bring in the contractor and say, “We were told we have two weeks to build a foundation. Do what you can.”

So they do what they can. Maybe it rains. Maybe some of the supplies don’t show up. And two weeks later, the inspector comes, looks around, says, “OK, the concrete is still wet right over there, that part’s not quite up to code … I’ll give it an 80 percent.”

In our field of psychotherapy, with over 400 models therapy, there are so many aspects to learn and get distracted by. Again, here is the problem: We lose sight and remain vague, abstract, and overwhelmed in our definition on what to work on. Instead, we go broad, and sacrifice deep. And when we go deep, we go into rabbit holes that make us none the wiser.

I worry we are barking up the wrong tree. We work on things that have suboptimal leverage on impacting our interpersonal therapeutic skills. Instead, we think that content knowledge will get us to there.

Here’s what Carl Rogers has to say about this, almost 78 years ago:

“The experience of every clinic would bear out the viewpoint that a full knowledge of psychiatric and psychological information, with a brilliant intellect capable of applying this knowledge, is of itself no guarantee of therapeutic skill.” (Rogers, 1939, in The Clinical Treatment of the Problem Child)

NO guarantee of therapeutic skill?? Good grief. Then what should I be working on? Here’s my best estimates at this point in time. It’s not in the domain of content or clinical knowledge. It’s got something more to do with process knowledge and conditional knowledge. (See my previous post on this topic, Three Types of Knowledge).

~~

Before we can adopt a philosophy of mastery learning, we first have to learn the art of being specific.

I remember during my primary school days, when we were first introduced to science lessons, we were given a little magnifying glass. Armed with this little contraption, I took it around with me during recess. We ended up skipping meals, and ran to the edge of the fences to burn things. Leaves, paper, even our textbooks or whatever we could get our hands on. The simple trick, as we applied our science lesson, was to find the sweet spot and focus the sun’s rays and slowly ignite the object. To discover smoke and fire. What a primitive delight.

Figure out what to work on that has the biggest leverage to improve your performance before you begin working at your craft.

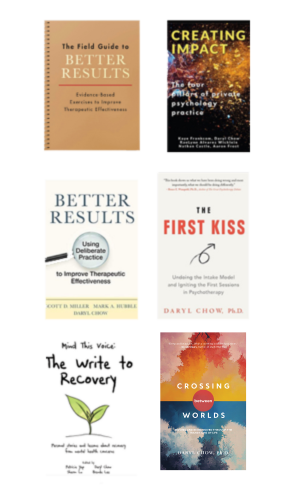

Fast forward a few decades, we are still playing with a different sort of magnifying glass. Scott Miller and I created what we call a “Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activites (TDPA; Chow & Miller, 2015*). This is aimed at guiding practitioners and supervisors in the art of leveraging and being specific. Stay tuned. In an upcoming APA book, edited by David Prescott, Cynthia Maeschalck, and Scott Miller, I’ve got a chapter related to the topic that speaks about the taxonomy, as well as issues on the practice and the practicals of deliberate practice. {Updated on 28th of August 2018. The book has since been released. Click HERE to check out Feedback Informed Treatment in Clinical Practice)

Here’s a question you can begin to ask yourself: “At this point of my professional development, What is the one thing I can to work on to get better at my craft?” Hint: Seek the advice of someone who is willing to know your work, and go back to the fundamentals.

Best wishes,

Daryl Chow, MA, Ph.D. (Psych)

Note:

*You can email me at daryl@darylchow.com if you would like to receive a copy of the taxonomy.

Thank you for this post! I enjoyed Sal Khan’s TED Talk and your blog post!

Good stuff bro. Looking forward to learning more.

Thanks. Sal Khan’s worth listening to. His efforts in the Khan Academy is so inspiring

A great post Daryl, especially since you drew on Sal Khan’s work. I refer parents to his free resources for helping their kids to master one level before moving on to the next. It’s a pity schools don’t make Mastery Learning & Direct Instruction standard practice.