In the previous post, we addressed the issue of how to receive feedback.

In this post, we take a step back and address how we can elicit feedback.

…But what questions should we ask?

But before we dive right in, ask yourself:

Do you really want to know? I used to find myself hesitant to ask for feedback when I know someone was amiss in the session. I’ve learned from my colleagues that this is common. What I learned is to point it out anyway, “You know Tim, I noticed that I might have missed something essential to you today. Am I mistaken? Can you help me figure out what that is, or what we could have explored further on?”

How we convey a sense of openness to the other person’s point of view will determine the type of feedback we get.

When we ask, ”Is everything ok today?” will skew towards a vocal-tic response, “Yeah. All good.”

Where we point the lens, it becomes the foreground. Discuss in advance what you are looking out for. While it may sound counterintuitive at first, take some time to process the following:

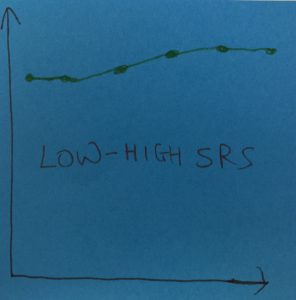

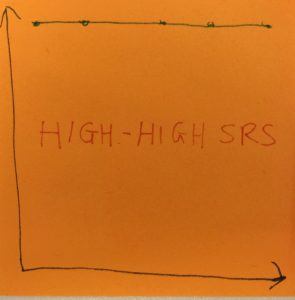

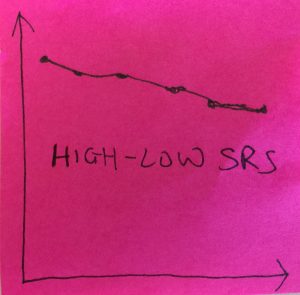

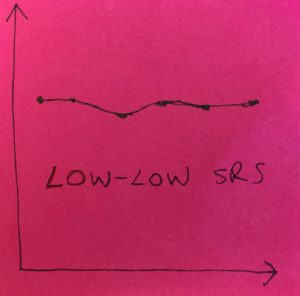

High session ratings of engagement by your client is not predictive of good outcomes (e.g., Owen, Miller, Seidel, Chow, 2016). In contrast, highly effective therapists seem to be able to elicit low engagement scores in early sessions. High alliance scores in the first session tells us nothing. The client could be truly happy with the session, or she might not feel safe to tell you how badly you missed her point today.

Do you know the average alliance formation trajectory among your clients? Which of the above fits your pattern?

We’ve also found in our initial Supershrinks study (Chow, 2014; Chow et al 2015. Stay tuned. We are on to some replication studies. More on that next time) that as compared to the average cohort, highly effective therapists are more likely to report being surprised by client feedback. That is, the top performers are more likely to report being surprised by client’s feedback that their counterparts. It does seem to suggest that the highly effective therapists are more willing to be corrected. They have a sense of openness to receive and consider client’s viewpoints, even if it may be contradictory to the therapist existing expectations.

Janet Metcalfe and colleagues suggest that individuals are more likely to correct errors made with initial high confidence than those made with low-confidence, so long as the corrective feedback is given (Barbie & Metcalfe, 2012; Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001; Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2006; Metcalfe & Finn, 2011). Although it may seem intuitive that deeply held beliefs are more entrenched and are the hardest to change, experimental studies have indicated that individuals are more likely to overwrite their responses and correct their beliefs (Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2001; Butterfield & Metcalfe, 2006), and are more likely to retain the correct answer compared to knowing the correct answer at the outset (Barbie & Metcalfe, 2012).

What? That’s a mouthful. Put it this way. Stand tall, and stand corrected.

Here’s some key points to remember when trying to elicit feedback from your clients at the end of a session:

1. Prime the Recall:

Give a good rationale WHY your client’s feedback about the session is crucial to you;

2. State What This is Not:

For example, “This is not an evaluation tool…You know how we are asked to do feedback surveys at restaurants? This is exactly what it’s not! Simply because those types of feedback, do not effect a change that will impact you. Your meal isn’t going to change because of your feedback. Here in the session, your feedback is important to me as it can help me tailor to fit you specifically…”

3. Juxtapose Open and Close Ended Questions:

Conventional wisdom argue to use open ended question. “What was the session for you?” Most of the time, this is too vague for clients. Instead, ask the specifics. “As you recall out what we talked about, and the exercise we did before we wrapped up, What was helpful to you?” After they share with you a response, follow it up with, “What was not helpful to you?” “…I know it’s tough to give feedback… we don’t normally tell others what we think, but your point of view is very important to me. I won’t take it personally, but I will take it very seriously…. cos’ sometimes, I just can’t see what I can’t see.”

4. Be Specific:

If you want specific feedback, be specific with your questions. “You know Kelvin, I got a feeling that I’ve pushed you too far today, especially when we were attending the issue about your fears. Am i mistaken?”

“What should I do more of?”

And

“What should I do less of?”

5. The Small of Things:

Say this, “You know as it’s hard to give someone feedback, I just want you to know that even if you think it’s a small or minor issue, please, I would love to hear about it.”

Cite examples: “You know, I once had a client who told me that I was too careful with her, and she wanted me to just be blatant with her. Do you feel that way too?”

As a form of closure, you can ask, “If there’s just one thing, what stands out for you today that you’d like to remember from our session?” Write that down, and begin to form ideas to bridge this into the next session.

Don’t forget to take a gamble on your own to make a prediction of how your client rates the session, before you see their ratings on the alliance measure. (see an older post that I talked about this practice, called Rate & Predict exercise)

All systems balances itself with a feedback loop. It’s up to us to elicit the specifics, and then follow through be an open and warm receiver. It’s abit like receiving presents during this Christmas. Be thankful.

At the time of this writing, I wish each of you a happy new year.

Best,

30th of Dec 2016

This is an important aspect of practice and success. I often included a similar discussion in my discussions about the use of self in practice. There are always opportunities to carefully listen to someone who may be yelling at you. As Marshall Rosenberg’s non-violent communication focus states when working with anger when someone is yelling they are asking for help. I am stubborn since birth and often have to step back and carefully hear the message delivered in a rash manner. The seeds of truth can sometimes be embedded in language we may dismiss or place barriers toward. Thank you for this reflection.

Thanks George. I have great respects for Rosenberg’s contribution to the field. I love what you said “The seeds of truth can sometimes be embedded in language we may dismiss or place barriers toward.”