“Those who control their passion and make it work for them have presence.

Those who fail to control their passion look like excited, nervous teenagers.

Those who have no passion at all have no presence.”

~ Dianna Booher, Creating Personal Presence.

Knowing the possible pitfalls is as helpful, if not more helpful, for the road ahead. If you are in search of a path to improve your own professional development, I recommend you get familiar with the following 10 things to avoid that will help you stay on track.

1. Having More Than ONE Area to Focus on Improving

Truth is, most therapists are pushed beyond the brink. On top of clinical practice, administrative duties, and fueled by a desire to read the latest and the greatest research publications—oh, how can I forget that we have a personal and family life— having more than one area to work on creates nothing short of overwhelming.

Feeling overwhelmed is not necessarily a function of having too much to do but rather not knowing what to do next.[1]

In the early stages of the development of the Taxonomy of Deliberate Practice Activities (TDPA), Scott Miller and I figured that therapists can focus on improving three of the identified from the list. After some months of working on it as a practitioner, I realised that even 2-3 areas to work on is OVERWHELMING. We began to get some feedback from others from the deliberate practice workshops that we run annually in Chicago (come join us this Aug’18!). I was not alone in this experience.

In the latest version of the taxonomy, after the ranking of the top 3 activities, we recommend drilling it down to ONE area to work on.[2]

2. Not Having ONE Specific Area to Focus on Improving

“Improve engagement,” is to vague a goal.

Sometimes the goal is to figure out the goal. Get focused on defining the goals, and get less wedded to solutions.

Let’s think this through: What consists of a good engagement? Goal consensus, emotional bond, agreement on approach and method?[3] What else? What aspects of the human interaction can facilitate resonance?

(See related post.)

3. Not Having A System of Practice

Once we’ve defined the ONE area to work on, we need a system to help us sustain this through our busy lives.

In order for deliberate practice to happen, we need a system of practice.

We can’t just rely on willpower; our energy needs to be channeled to clinical practice and deliberate practice, not “when to practice”. Instead, we need to rely on a system of practice, and **automating** this process so that we do not need to be thinking, “ok, when I get some free time,” or “Ok, let’s see if a client cancels today, and I’d slip in some deliberate practice.”

4. Trying to “Do Deliberate Practice” in a Particular Method

This point often surprises people I coach. Focusing on specific methods has little to no leverage on actually improving your outcomes; let alone focusing on a specific feature of a specific method.

Do not turn deliberate practice into a noun. Instead, deliberate practice is a framework for engaging in focused and deep work, aimed at getting better at achieving better results with your clients.

Gleaning from the study of expertise and expert performance, the following are the four tenets of deliberate practice:

See our recent edited hapters for an elaboration on how these four tenents apply to our efforts in deliberate practice:

Chow, D. (2017). The practice and the practical: Pushing your clinical performance to the next level. Prescott, David S [Ed]; Maeschalck, Cynthia L [Ed]; Miller, Scott D [Ed] (2017) Feedback-informed treatment in clinical practice: Reaching for excellence (pp 323-355) x, 368 pp Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; US, 323-355.

Professional development: An Oxymoron? In T. Rousmaniere, R. K. Goodyear, S. D. Miller, & B. Wampold (Eds.), The Cycle of Excellence: Using Deliberate Practice in Supervision, Training, and Independent Practice (pp. 23-47). River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, USA: Wiley Press.

Finally, instead of focusing on specific therapeutic models/methods, focus on making clear your first principles. (See the series of blogposts on first principles, I, II, III).

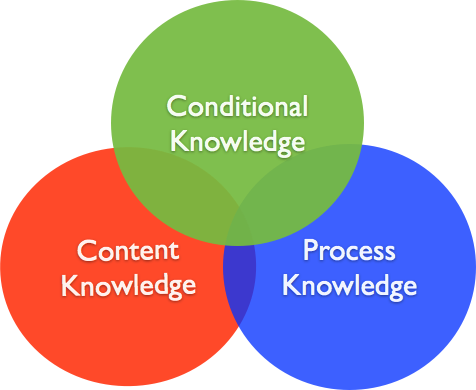

5. Focusing Exclusively on Content Knowledge

Sometimes there is indeed a gap in our knowledge in a particular issue our client presents (i.e., content knowledge). When that happens, go read up about it.

However, most issues that therapists face relate to process knowledge and conditional knowledge.

6. Focusing on the Numbers

Early adopters of routine outcome monitoring or feedback informed treatment (FIT) tend to get fixated with the numbers.

It’s not about the numbers.

It’s not about the reliable change index or the clinical cutoffs.

It’s about the story behind the numbers.

(see related post)

7. Emphasis on the self

While we are to work on improving our craft, we must not lose sight that the emphasis is not on the egoic self. Instead, the emphasis is to help our clients optimise the chances of experiencing growth, relief from suffering, and benefit from their encounter with you.

Think of it this way: We need more outrospection than introspection. We need to focus more on being helpful than on being good.

So when you are working to improve your craft, focus on your client.

(See related post)

8. Not Consulting a Mentor

I often asked clinicians and clients alike, “Who has guided you in your life that has created an impact?” It’s such a heartache to hear that many people had no one to turn to for guidance.

Richard Rohr says that too many people are “father hungry.”

Contrary to the genre, there is no such thing as “self-help.” Even when we are reading a book for guidance, the author is providing some instrumental help to the active reader.

Somewhere in our culture (and literature), we are led to believe that when we get older with more experience, we know how to help ourselves in designing a way to improve our work. Maybe that’s why it’s “lonely at the top.”

It’s hard to see what we can’t see.

9. Detached Professional Development from Actual Client Outcomes

We play differently when we are keeping score [4]. Don’t believe this? Just watch a bunch of kids playing basketball. They play very differently when they are just shooting around, compared to when a game is on and they are keeping scores.

Attending workshops, trainings, and supervision without an idea on how your clients are doing is like bowling with a curtain covering the pins; you don’t know if it’s a strike, a spare, or a complete miss (okay, maybe if you heard the pins, it would mean that at least you’ve hit a pin).

I argue that too much effort, time and money is wasted on CE/PD activities. It may make us feel good (“I found this course so helpful”), but it does not translate to actual benefit for our clients.

10. Supervision That Does Not Translate to Improvement

We have less of an excuse for supervision than on other professional development activities.

Supervision is meant to be individualised, isn’t it?

I worry that supervisors spend too much time on content knowledge and less on process and conditional knowledge—and crucially, there’s a lack of staying close to actual client outcomes.

(See these two related posts on clinical supervision: I & II)

p/s: There’s a little more time left. Join us for the in-depth online course Reigniting Clinical Supervision. If you are a subscriber to this list, you will be given a 50% discount code for this course. Offer ends on the 31st of Jan 2018.

YOUR TURN: What are some pitfalls you recommend we should avoid in our path of professional development? Love to hear from you in the comments below.

Best,

Daryl

Footnotes:

[1] I borrowed this a citation in Michael Port’s book, Steal the Show, from Matthew Kimberly.

[2] You can email me for a copy of the taxonomy of deliberate practice activities daryl@darylchow.com

[3] See Bordin (1979) classic study that many researchers still use to define therapeutic alliance: Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252-260. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

[4] McChesney, C., Covey, S., & Huling, J. (2012). The 4 Disciplines of Execution. London: Simon and Schuster UK Ltd.

This listing was most helpful. I was impressed that you reference Richard Rohr. When I was a Catholic, I remember reading his work in the 1970s and 1980s. I respected his work and wisdom. I have always been focused on several directions, however your point about settling on one from the list one generates makes sense. Developing skill mastery one skill at a time makes sense. The idea of focusing on being helpful rather than being good. This idea of being or doing is an interesting dynamic. “Doing” activities that help the client, and the client is improving indicates therapeutic success. Last, your observation about attending feel good continuing education workshops with no change in practice, is indeed not effective.

ha! well said, George.

I’m a huge fan of Richard Rohr’s work, particular his more recent book, Falling Upward.